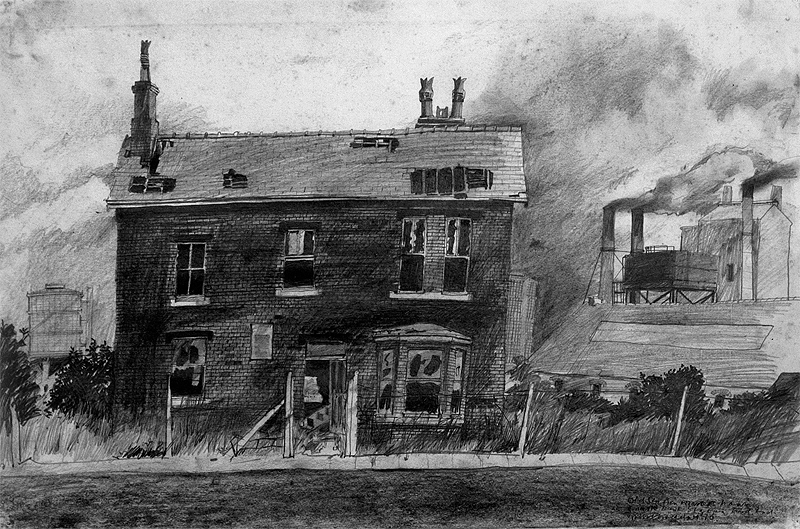

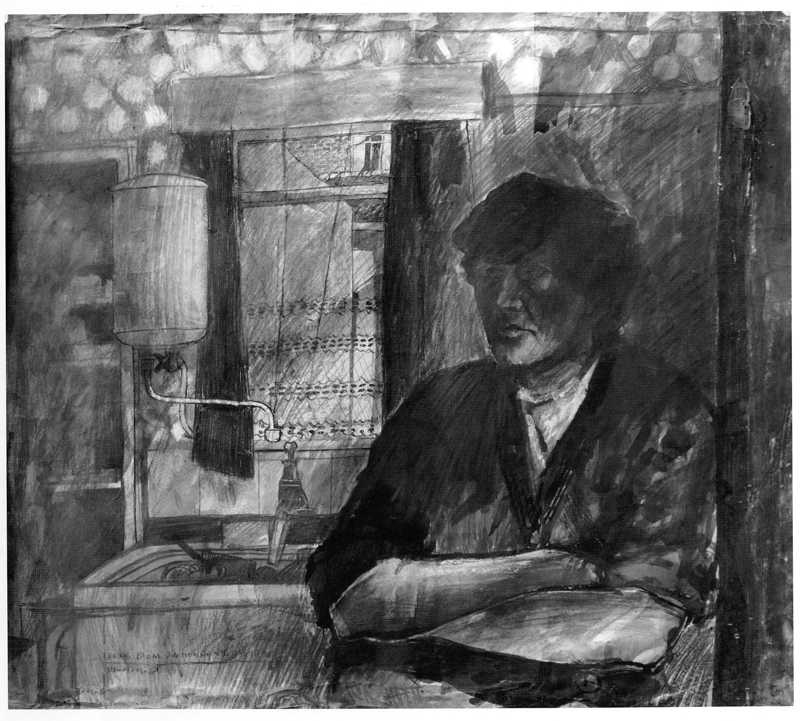

Chances are you won’t have heard of David Mulholland (1946-2005), a painter of and from Middlesbrough. Until last year, when a group of friends devoted to the preservation of his memory sent me some of his pictures, neither had I. The work hit me immediately as authentic, born of intimate feeling for its subject. Most affecting were powerful graphite and wash drawings of blackened industrial places populated by persevering working people. Having edited a couple of art papers for over twenty years, I felt that if anyone had a right to have heard of David Mulholland then it was at the very least someone in my position.

Chances are you won’t have heard of David Mulholland (1946-2005), a painter of and from Middlesbrough. Until last year, when a group of friends devoted to the preservation of his memory sent me some of his pictures, neither had I. The work hit me immediately as authentic, born of intimate feeling for its subject. Most affecting were powerful graphite and wash drawings of blackened industrial places populated by persevering working people. Having edited a couple of art papers for over twenty years, I felt that if anyone had a right to have heard of David Mulholland then it was at the very least someone in my position.

What follows is a lament for the establishment’s theft of the richness of our culture. Over decades now, by advancing its prejudices to the exclusion of everything else, art authorities have conspired to deny us sight of so many whose works were valuable testimonies of their time and experience. For their own ends, these all-powerful administrators have kept us in the dark.

David Mulholland is typical of many accomplished and original 20th century British artists whose names are deservedly kept alive by friends who loved him and knew his worth as both commentator and poet, but who is unknown to the rest of us. No galleries funded by the Arts Council, for example, would dare show the work of these artists even if they wanted to. Mulholland is typical of painters derided by the self-appointed in State Art and sneered at by decision makers. By arts bodies obsessed with ‘innovation’ and the ‘cutting edge’ he is, in that infamous Arts Council phrase “the wrong kind of artist”. Yes, those are the words they use – the wrong kind of artist. What right have they to use a phrase like that? Who do these people think they are?

As one who described with affection his experience of the hard lives and resilience of poor people, and evoked the gaunt beauty of the tough places in which they lived and worked, Mulholland was “the right kind of artist”. The only kind of artist. He is certainly among those whose work is likely to survive appreciated long into the future. His work was done because it needed to be made, because the observations of a brutal working life and cruel industry, of pleasures and strifes, of hard graft and redundancy, demanded interpretation by an artist. Mulholland’s work doesn’t need a page of unreadable tosh by one of Serota’s army of scribblers in order for you to know what it’s about. Its love for a location and people speaks for itself. In the future, say a century or more from now, those looking at Mulholland’s work will understand without prompting its concerns and causes, what stories it has to tell, and why it has lasted. In all good art, these qualities are self-evident, although in some artists they may take longer to appreciate.

Mulholland was born in South Bank, a community on the Tees built around quaysides, three blast furnaces, steel rolling mills and fingers of cindery railway sidings. In photographs of the place in its heyday, and before the works closed, it looks smokily Soviet in its concentration of polluting ad hoc production. It’s the sort of place which, if you are born there, is in your blood forever. As landscape painter Len Tabner, another important local and friend of Mulholland, said at the recent opening of his memorial exhibition at the Dorman Museum in Middlesbrough, “Dave went all the way to Byam Shaw and to the Royal College of Art in London but only ever painted South Bank.” Apart from a brief foray as a young seaman, when he painted foreign scenes, it remained that way. He eventually returned home, taught art unconventionally in a secondary school, painted his life and friends, and sometimes the surrounding countryside. His work records a personal journey and history.

Mulholland was born in South Bank, a community on the Tees built around quaysides, three blast furnaces, steel rolling mills and fingers of cindery railway sidings. In photographs of the place in its heyday, and before the works closed, it looks smokily Soviet in its concentration of polluting ad hoc production. It’s the sort of place which, if you are born there, is in your blood forever. As landscape painter Len Tabner, another important local and friend of Mulholland, said at the recent opening of his memorial exhibition at the Dorman Museum in Middlesbrough, “Dave went all the way to Byam Shaw and to the Royal College of Art in London but only ever painted South Bank.” Apart from a brief foray as a young seaman, when he painted foreign scenes, it remained that way. He eventually returned home, taught art unconventionally in a secondary school, painted his life and friends, and sometimes the surrounding countryside. His work records a personal journey and history.

Given the enormous sums now thrown uncritically and unchallenged at contemporary art, one ought to feel safe that excellence in whatever style or medium is somewhere being brought to our attention. But despite the fact that, courtesy of the National Lottery, there are expensive immense new galleries all over the country, the opposite continues to be true. The same few artists dominate news, features and critical coverage. They also dominate all the new galleries because these are controlled exclusively by State Art believers. For them, a foreign artist of no discernible distinction, spotted amidst the trendy jumble and waffle of an international biennale, will always take precedence over the likes of Mulholland.

If you live in the north, as I do increasingly, you can find Anish Kapoor signing books in Middlesbrough – where his £2.5 million ‘regenerating’ fishing net was unveiled two years ago and still stands bleakly abandoned and pointless in wasteland – and at a retrospective in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park (see Moping Owl, p. 10). In London he is at Lisson Gallery, all over the Royal Academy, and even lording it over the Olympics’ site. No wonder he needs 25 assistants and three studios to churn out his coloured holes and facile shiny mirrors to meet demand. Such a monoculture as is represented by Kapoor doesn’t add to the diversity we deserve, because the rooms he and his ilk occupy with stupefying frequency are denied to others. Newspaper profiles of Kapoor last aired only three months ago when The Orbit was unveiled – having already appeared on dozens of occasions over the last twenty years – have again been warmed up and paraphrased by others for his new shows in London and Yorkshire. This insulting process of indoctrination goes unmentioned elsewhere, as though it’s taken for granted that only a handful of artists merit such relentless promotion. The only difference in these disgustingly fawning and uncritical pieces is the sentence where they state what Kapoor is currently worth – and it keeps getting bigger, the last number cited being £80 million. For the rest of us, it is impossible not to know Kapoor’s life story off by heart. If only it were interesting. If only all this approbation were the result of his having produced something truly outstanding and comparable with the best from the past… But all that emerges is more of the same branded deluxe ornaments for the grotesque mansions of the immodest rich. And please believe me when I say there is no point in visiting his exhibition at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, because you’ve seen it many many times before. It takes seconds to walk around. And, do you know what, some of the holes are so dark you can’t be quite sure where the bottom is. How clever is that?

If you live in the north, as I do increasingly, you can find Anish Kapoor signing books in Middlesbrough – where his £2.5 million ‘regenerating’ fishing net was unveiled two years ago and still stands bleakly abandoned and pointless in wasteland – and at a retrospective in the Yorkshire Sculpture Park (see Moping Owl, p. 10). In London he is at Lisson Gallery, all over the Royal Academy, and even lording it over the Olympics’ site. No wonder he needs 25 assistants and three studios to churn out his coloured holes and facile shiny mirrors to meet demand. Such a monoculture as is represented by Kapoor doesn’t add to the diversity we deserve, because the rooms he and his ilk occupy with stupefying frequency are denied to others. Newspaper profiles of Kapoor last aired only three months ago when The Orbit was unveiled – having already appeared on dozens of occasions over the last twenty years – have again been warmed up and paraphrased by others for his new shows in London and Yorkshire. This insulting process of indoctrination goes unmentioned elsewhere, as though it’s taken for granted that only a handful of artists merit such relentless promotion. The only difference in these disgustingly fawning and uncritical pieces is the sentence where they state what Kapoor is currently worth – and it keeps getting bigger, the last number cited being £80 million. For the rest of us, it is impossible not to know Kapoor’s life story off by heart. If only it were interesting. If only all this approbation were the result of his having produced something truly outstanding and comparable with the best from the past… But all that emerges is more of the same branded deluxe ornaments for the grotesque mansions of the immodest rich. And please believe me when I say there is no point in visiting his exhibition at the Yorkshire Sculpture Park, because you’ve seen it many many times before. It takes seconds to walk around. And, do you know what, some of the holes are so dark you can’t be quite sure where the bottom is. How clever is that?

The neglect of so many for the sake of so few is a phenomenon of the celebrity culture. How long will it be before this system is exposed as a monumental racket dreamed up by a cabal of public officials, commercial dealers and auctioneers with the aim of creating false gods, rigging the market and handsomely feathering the nests of all concerned. Watching this process as it unfolds is sickening and the fact that they have not seen fit to investigate this monopoly brings disgrace on the Culture Select Committee of the House of Commons. They could have made a difference, if only by establishing once and for all that such an all-powerful orthodoxy exists in contemporary art, whose purpose is to discriminate against the likes of David Mulholland.

Increasingly, I resent this editing of what we’ve been allowed to see, dictated as it is by the tastes of half a dozen bureaucrats with Serota at their head. This President-For-Life has singlehandedly done more damage than anyone in the history of British art to the public’s ability to see the work of a wide range of British artists. He is a self-important scourge building ever greater monuments to his own vanity and tastes, and yet he receives an uncritical press. When is this fellow going to go, and leave us alone? How long will it be before curators in regional galleries can see all art again for its qualities and not be forced to follow trends out of fear for their careers?

If it is not the work of regional galleries to show the work of their best local artists what is it their job to do? And what an irony it is that the modern art gallery in Middlesbrough is showing coincident with Mulholland’s memorial show an exhibition dealing with “concepts of ‘home’” … starring Tate trustee Jeremy Deller.

David Mulholland spoke a local language, a ‘home’ language, which is understood internationally by all people. No human being is excluded from its sentiments. State artists talk an international language which, like esperanto, is understood by hardly anyone. There ought to be room for both persuasions, but we are force fed only one.

David Lee

The Jackdaw November-December 2012