“Maybe a man’s name doesn’t matter all that much.” (Orson Welles in F For Fake)

As so many gifted painters have discovered to their cost, having an unusual talent is not necessarily a passport to a meteoric career. So many whose abilities deserve to be recognised, or at the very least acknowledged, struggle cruelly in obscurity if not in the proverbial garret. Such neglect may drive certain temperaments to desperate measures. The inability of the meritorious to make a living is doubly harsh when the infantile antics and stunts of contemporary art are plastered daily across the newspapers. When only the most strident and outrageous get noticed the world of art becomes a strange and unfair place.

An art college lecturer recently advised her imminently graduating painters and sculptors that if they wished for a successful career they should employ with immediate effect the most expensive public relations company they could afford. She was effectively informing her charges of the unpleasant truth that in contemporary art it’s not the quality of the work produced that will make you famous, but more importantly how shrewdly and relentlessly you are marketed and branded as an individual. In terms of high sales and escalating prices, success in art is unfortunately directly proportionate to the public visibility of the artist. Thus has our age of mindless celebrity worship sullied even the hallowed halls of art.

As the last hundred years have proved, dealers in Modern Art can sell any old rubbish against the perception of success and a secure investment. In the world of those collectors desperate to be fashionable it won’t matter what a work looks like, because to them art is like so many shoes, cars, handbags or jewels – they will buy anything if the label is recognisably expensive and their friends are suitably impressed by them having paid so much for so little. These few words tell you most of what you need to know about the depressing condition of official contemporary art and its market. It is also why good artists of more conventional abilities have a harder time of it than they deserve.

There is, however, another way to make it as an artist, though it is not one recommended for those of a nervous disposition. This requires being that increasing rare species a gifted painter … and serving four months in Brixton for wholesale faking of works by famous artists. No better way exists of getting noticed and nothing on an artist’s CV looks quite so impressive as a stretch for forgery. It is hard for many of us to resist a talented and essentially harmless rogue. The names of these great fakers live in folklore: Hans van Meegeren (Vermeer), Elmyr de Hory (Picasso, Modigliani, van Dongen), Tom Keating (Samuel Palmer, Cornelius Krieghoff), Eric Hebborn (old master drawings, including Leonardo da Vinci), the great Shaun Greenhalgh (Lowry, Gauguin, Hepworth) – and in the case of the avuncular and telegenic Keating he became better known to the public than the names of the artists he faked. In a world where publicity is the key to artistic success, money can’t buy the quantity of front-page publicity received for perpetrating an infamous crime. Ironically, fakers frequently enjoy stellar careers once they are going straight. Cynics might even argue that it’s well worth enduring a brief diet of bread and water in order to enjoy a comfortable career thereafter.

John Myatt is only the latest in a long line of great British forgers with notoriety and infamy as his calling cards. The extent and audacity of his crime were breathtaking – I still can’t believe he got away with it. He was part of arguably the most sophisticated fraud in the faking of paintings ever perpetrated, and certainly the most impressive in recent memory. Over a period of nine years beginning in 1986 he faked as many as 200 works by assorted 20th century painters and draughtsmen, only sixty of which have ever been recovered by police. Some of the remainder are undoubtedly still hanging in museums and private collections where they are being revered and enjoyed as originals.

Many puritans will find John’s record objectionable. He was, after all, polluting the oeuvres of famous artists with lies: is there a more serious crime against art than this? Perhaps not. Others may sympathise, and even admire his exposure of bogus expertise among those claiming special insight. Let’s face it, few revelations are as satisfying as seeing a self-important connoisseur covered in egg. Unfortunately, I have personal experience of this. Awarding first prize in a landscape painting competition to an unknown artist for a work far more accomplished than the amateurish standard of the other entries, I remarked to the organisers how the picture looked vaguely familiar. Indeed, the winner had copied accurately a work from the reserve collection of the Tate Gallery and passed it off as his own invention. I ought to have recognised it instantly, but didn’t. When the deceit emerged, newspapers and colleagues enjoyed sport at my expense.

John reminded us how the apparent superiority and invulnerability of those in the art trade is in fact all too often a trick of the light, and the flash suit. He deserves our thanks for that.

Always a keen painter at school John moved on logically to art college and for a while thereafter he was – like so many frustrated painters – a teacher of art in a secondary modern. Confident in his technique, he fell into faking at a time when, as a single parent, he was struggling to support his children. Then, like so many other fakers, once illegality and its ready profits had him in its clutches he couldn’t extricate himself. There is no question he boasts all the requisite qualifications for a top forger, principle among which is being able to examine the works of a celebrated artist and absorb their subjects, forms and colours to the degree that he is then able to create a convincing new work from scratch. He came unstuck only when his ‘Giacomettis’ and ‘Ben Nicholsons’ were shown to scholars so steeped in the work of these artists they were probably as adept at identifying a fake as the artist himself would have been.

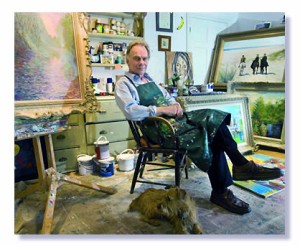

Since he came out of prison John has turned his dishonesty to honest profit, producing versions of masterpieces for those who admire but can’t afford the multi-million pound originals. And he is brilliant at it, the adopted styles being instantly recognisable. A fascinating aspect of what John does is the way looking at what he paints is complicated by a personal history one can’t overlook. You aren’t just getting a copy of a masterpiece or an interpretation of a style by a great copier, you’re getting the work of someone whose efforts were at one time actually confused with the real thing. He is asking us to decide for ourselves if the authenticity of what we see is quite as important as we are led to believe it is. Scholars and historians will, naturally, want to know they can rely on the veracity of what they are looking at, but for the rest of us does it really matter that much? Most of us can live with a harmless deception. Viewing a work which is not by the artist you suppose is hardly the end of the world.

Ask yourself this: what is the difference between looking at a Monet and viewing something which you believe to be a real Monet? The answer is nothing; that is, at least while ignorance prevails. It has recently been proven by psychological experiment that belief in the authorship of a painting is not only crucial to its appreciation but also seriously affects how long we are prepared to look at it. Belief in the originality of what we are looking at, its association with a famous name, causes greater enjoyment. But if we appreciate a painting why do we not continue to like the same painting when its authorship is downgraded. Should it really make so much difference?

Consider this very recent example of faking. A wealthy resident of Venice from a noted family visited his friends’ houses socially for years and coveted their collections of Old Masters. Using quite exceptional guile and planning, he had created exact facsimiles of their works and placed the copy in the original frame while the owners were out of town. Over a period of years he amassed several dozen original old masters using this method, which he proceeded to sell. So brilliant were the copies that the paintings’ owners were none the wiser that they weren’t looking at the originals, until police alerted them to the truth. The perpetrator of this crime realised that for most people who look, or glance, at art there is no difference in impact between an original and a copy. How many of us could honestly tell the difference? Where art is concerned most of us believe what we are told by those we assume know more than ourselves. We accept appearances at face value, and are happy to enjoy innocently.

So why not indulge yourself in a little self-deception with an original John Myatt? If you can’t afford a real Monet, Matisse or Modigliani then a Myatt is undoubtedly the next best thing. It is expertly done, pleasing to look at … and just think of the stories, true or false, you might tell your friends about it. http://www.washingtongreen.co.uk/artists/john_myatt/

David Lee

October 2012