Of the 183 works by John Piper in the Tate’s collection none is currently on display. One of the major British artists of early Modernism does not have a single item of his work on show in the national collection of British art, of which, incidentally, he was once considered sufficiently eminent to serve as a trustee. How could such an aberration occur?

As an apostate Modernist, Piper has been marginalised as a glib illustrator of churches and grand houses in a vaguely modish idiom. He is perhaps a victim of his divers interests and abilities; he was writer, typographer, photographer, textile and stage designer, stained glass maker, muralist, printmaker, painter, but – especially – a lover of England, its idiosyncracies of belief, custom and culture, and especially of its history, in which he was thoroughly well-read. As a forgotten man he is perhaps the first example of an important artist who, by deviating from the consensus of an official taste which would later emerge as State Art, spoke out and stuck to his convictions. Thus, he managed to get himself on the wrong, ‘Betjeman’ side of the debate when Modernism began to rule the critical roost in English art and commenced its relentless infiltration and systematic cleansing of institutions. There was no schism with his former vanguard friends, Piper simply moved in his own direction rather than following trends and styles he considered useful and intellectually stimulating but limiting as far as his own ambitions were concerned. He inclined towards the deadly sin of Romanticism, being spellbound by land, its natural evolution and the alterations that Man’s brief occupancy had so far wrought upon it. Crucially, he wished to convey his affections to as many as possible, whereas his youthful espousal of Surrealism and Abstraction, though fascinating, were ultimately exclusive, remote and too dismissive of past art. Art, he felt, had become in danger of isolating itself, of communicating only to its few devotees rather than to a wider audience. Most of all Piper relished observation. His concentration was informed by a probing intelligence typical of the genuinely curious.

As an apostate Modernist, Piper has been marginalised as a glib illustrator of churches and grand houses in a vaguely modish idiom. He is perhaps a victim of his divers interests and abilities; he was writer, typographer, photographer, textile and stage designer, stained glass maker, muralist, printmaker, painter, but – especially – a lover of England, its idiosyncracies of belief, custom and culture, and especially of its history, in which he was thoroughly well-read. As a forgotten man he is perhaps the first example of an important artist who, by deviating from the consensus of an official taste which would later emerge as State Art, spoke out and stuck to his convictions. Thus, he managed to get himself on the wrong, ‘Betjeman’ side of the debate when Modernism began to rule the critical roost in English art and commenced its relentless infiltration and systematic cleansing of institutions. There was no schism with his former vanguard friends, Piper simply moved in his own direction rather than following trends and styles he considered useful and intellectually stimulating but limiting as far as his own ambitions were concerned. He inclined towards the deadly sin of Romanticism, being spellbound by land, its natural evolution and the alterations that Man’s brief occupancy had so far wrought upon it. Crucially, he wished to convey his affections to as many as possible, whereas his youthful espousal of Surrealism and Abstraction, though fascinating, were ultimately exclusive, remote and too dismissive of past art. Art, he felt, had become in danger of isolating itself, of communicating only to its few devotees rather than to a wider audience. Most of all Piper relished observation. His concentration was informed by a probing intelligence typical of the genuinely curious.

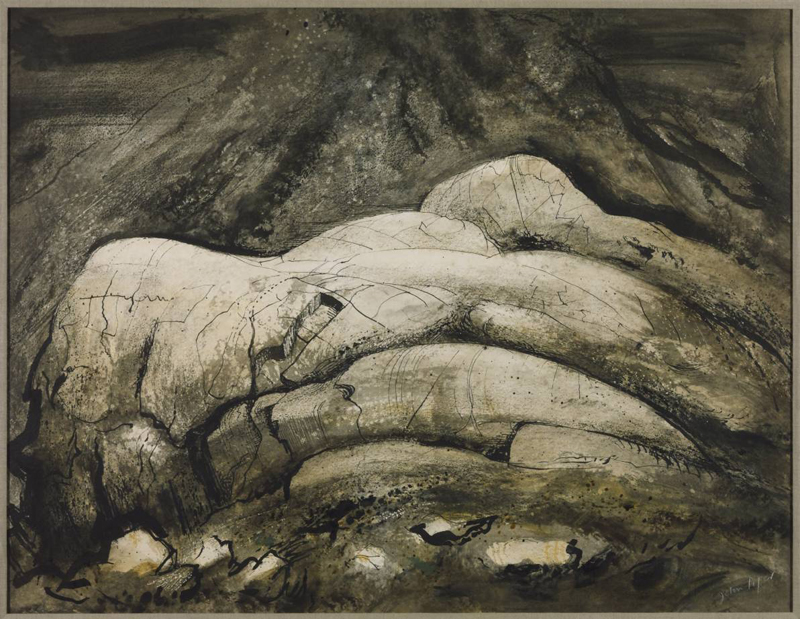

A small exhibition at Whitworth Art Gallery in Manchester (9 February to 16 June) displayed Piper’s paintings done during the artist’s visits to Snowdonia in the 1940s. It reminds us of what a powerful and original artist he was. Of several outstanding pictures, which are as good as anything by other British artists from this time, one in particular seemed to encapsulate everything Piper sought and stood for. It depicts the Nant Ffrancon valley as a living, dramatic place whose appearance is dictated by its slow forming by glaciation. In such places Piper’s imagination and speculation ran riot. Rock is alive, work in progress. The experience of such a picture encourages even seasoned lookers to see and appreciate more intensely any genius loci. http://www.whitworth.manchester.ac.uk/whatson/exhibitions/johnpiper/

This astonishing picture was sold two years ago for £17,000 – that is, under half what Hirst was charging at his recent Tate Mart for a signed poster exhibiting no discernible artistic merit. Good luck to the perceptive individual who acquired this modest treasure. But why is it so obviously a silly question to ask if a single British gallery or museum had noticed this profound painting and bothered to bid for it. There is a similar though inferior example from the same series depicting a nearby motif in the Tate’s collection, which needless to say is not on show. £17,000 for a masterpiece when signature decorative froth by Picasso sells for over a hundred million…

We have the wrong brainwashed curators frightened to acknowledge diversity and following the wrong narrow trends; the wrong art market rigged solely for investment and profit; the wrong craven museum directors too willing to toe the establishment line; and we are constantly force-fed the wrong art which boasts so much yet delivers so little. Piper should be on show and permanently celebrated. He died in 1992, and there has been mounted no retrospective of his work since 1982.

If your interest in the history of British art extends beyond the fashionable and you haven’t yet read Frances Spalding’s beautifully written joint biography of John and Myfanwy Piper (Oxford University Press, £16.99 pb, a tenner on Amazon) then it’s about time you did: you’re in for a most edifying journey.

David Lee

May/June 2013

![[no title] 1978 by John Piper 1903-1992](http://www.thejackdaw.co.uk/wp-content/uploads/2013/07/Piper2.jpg)