I spent a month recently in a 12th-floor ward of the new Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel. Except for the thrilling views of the capital it provides, it is an undistinguished public building, not least because like all hospitals nowadays its corridors are lined with ‘Art’. Not even I could raise a flicker of interest as I was wheeled, sitting or prone, backwards and forwards along passages lined with studio fillers and eyesores. Indeed, more than once I felt an urge to damage the more bombastic abstract daubs which I grew to loathe: their irrelevant avoidance of a subject was an insulting imposition in the context of such lived anxiety and discomfort. Who do these hospital administrators and self-styled ‘curators’ think they’re kidding about the therapeutic value of this stuff? And in all the weeks I didn’t see a single other person stop to look at anything – in this respect it reminded me of the National Gallery. Fortunately, my ward was spared this nonsense. The only visual interest was in the picture window views of what for those of us peering out was a very distant seeming and wistful outside world.

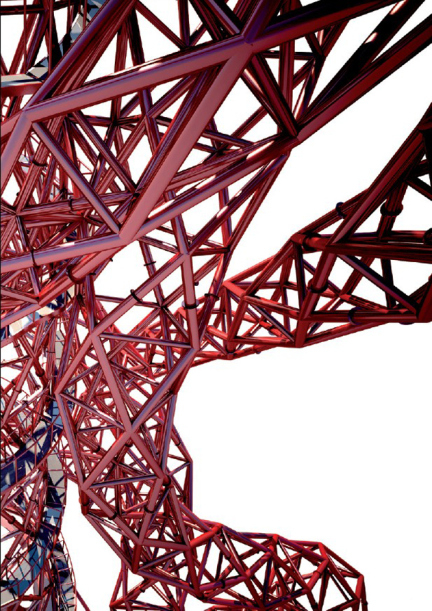

From my bed I had the worst possible view, a panorama restricted by the hideous wing opposite. It looked north east away from our great meandering river, City monoliths, pretty Wren churches and Greenwich majesty, towards the suburban wasteland of Walthamstow and Gant’s Hill. Central to this limited aspect was our Airfix Olympic stadium with its pet cancer … Anish Kapoor’s Orbit. Disappearing anonymously among cranes and building sites, the little Indian’s inoperable whimsy looked as helpless as any other unfinished structure. Every time I opened my eyes there it was, drug-induced hallucination having the power to transform it into visionary torture. I knew exactly how Macbeth felt at the banquet – “quit my sight”. And every time I wondered what the hell it was there for.

From my bed I had the worst possible view, a panorama restricted by the hideous wing opposite. It looked north east away from our great meandering river, City monoliths, pretty Wren churches and Greenwich majesty, towards the suburban wasteland of Walthamstow and Gant’s Hill. Central to this limited aspect was our Airfix Olympic stadium with its pet cancer … Anish Kapoor’s Orbit. Disappearing anonymously among cranes and building sites, the little Indian’s inoperable whimsy looked as helpless as any other unfinished structure. Every time I opened my eyes there it was, drug-induced hallucination having the power to transform it into visionary torture. I knew exactly how Macbeth felt at the banquet – “quit my sight”. And every time I wondered what the hell it was there for.

To discover if it owned any sense I tried drawing it, but it was formless and ungainly, without distinctive mark or symbol, rhyme or reason. Nothing commended it. Neither were the nurses any more insightful. Most hadn’t noticed its existence and of the remainder not one had a kind word, the most frequent observation being: “What’s it supposed to be?” (Incidentally, this is an intelligent question.) Given the shortages, abuse and poor conditions under which these generally marvellous carers toil, this ‘sculpture’ seemed a public folly too far.

Orbit is a perfect example of the trash you get if you allow art to be governed by a small number of people with mutual interests, none of which concerns public desires or needs. For this is specialist gallery art foisted on a bemused populace. Orbit is and will remain meaningless to everyone who looks at it. It will never become a source of national pride or a rousing emblem because, unlike, say, the Peel Monument on the Pennine ridge above my home town, it is not assertive, commemorative or instantly recognisable, and being asymmetrical, it has no fixed image in memory, no face, no charm. It is the opposite of beautiful and it tells no story and invites no thought. Also, it fails the important Lavender Hill Mob Test: no one will buy a souvenir Orbit in the way that millions own dinky Eiffel Towers, whether of stolen gold, base metal or otherwise.

Like all the art commissioned for the Olympics which was supposed to form part of the event’s legacy, Orbit is a characterless failure and represents a missed opportunity precisely because it was the result of a State Art establishment stitch-up. Wherever you look into its evolution, all over it are the mucky fingerprints of President-For-Life Serota and his Usual Suspects. Whenever this shower is involved you just know you’re going to get overhyped, over-rated, overpriced shit.

An essential of public art is that you know what you are looking at and why it was put there. This demands that an artist explores beyond his own motivations and aspires to tap a collective spirit. But, of course, this is precisely the self-effacing quality of which tenth-raters in contemporary art are incapable.

David Lee

Out of touch

I spent a month recently in a 12th-floor ward of the new Royal London Hospital in Whitechapel. Except for the thrilling views of the capital it provides, it is an undistinguished public building, not least because like all hospitals nowadays its corridors are lined with ‘Art’. Not even I could raise a flicker of interest as I was wheeled, sitting or prone, backwards and forwards along passages lined with studio fillers and eyesores. Indeed, more than once I felt an urge to damage the more bombastic abstract daubs which I grew to loathe: their irrelevant avoidance of a subject was an insulting imposition in the context of such lived anxiety and discomfort. Who do these hospital administrators and self-styled ‘curators’ think they’re kidding about the therapeutic value of this stuff? And in all the weeks I didn’t see a single other person stop to look at anything – in this respect it reminded me of the National Gallery. Fortunately, my ward was spared this nonsense. The only visual interest was in the picture window views of what for those of us peering out was a very distant seeming and wistful outside world.

To discover if it owned any sense I tried drawing it, but it was formless and ungainly, without distinctive mark or symbol, rhyme or reason. Nothing commended it. Neither were the nurses any more insightful. Most hadn’t noticed its existence and of the remainder not one had a kind word, the most frequent observation being: “What’s it supposed to be?” (Incidentally, this is an intelligent question.) Given the shortages, abuse and poor conditions under which these generally marvellous carers toil, this ‘sculpture’ seemed a public folly too far.

Orbit is a perfect example of the trash you get if you allow art to be governed by a small number of people with mutual interests, none of which concerns public desires or needs. For this is specialist gallery art foisted on a bemused populace. Orbit is and will remain meaningless to everyone who looks at it. It will never become a source of national pride or a rousing emblem because, unlike, say, the Peel Monument on the Pennine ridge above my home town, it is not assertive, commemorative or instantly recognisable, and being asymmetrical, it has no fixed image in memory, no face, no charm. It is the opposite of beautiful and it tells no story and invites no thought. Also, it fails the important Lavender Hill Mob Test: no one will buy a souvenir Orbit in the way that millions own dinky Eiffel Towers, whether of stolen gold, base metal or otherwise.

Like all the art commissioned for the Olympics which was supposed to form part of the event’s legacy, Orbit is a characterless failure and represents a missed opportunity precisely because it was the result of a State Art establishment stitch-up. Wherever you look into its evolution, all over it are the mucky fingerprints of President-For-Life Serota and his Usual Suspects. Whenever this shower is involved you just know you’re going to get overhyped, over-rated, overpriced shit.

An essential of public art is that you know what you are looking at and why it was put there. This demands that an artist explores beyond his own motivations and aspires to tap a collective spirit. But, of course, this is precisely the self-effacing quality of which tenth-raters in contemporary art are incapable.

David Lee

Share: