Lowry deserves treatment as a serious artist, though more usually such an approach is denied him because of, firstly, his suspiciously wide popularity and, secondly, what is mistakenly characterised as stylistic primitivism. A strong whiff of the patronizing informed reviews of this exhibition, as though the work was a tad unsophisticated for critics used to rambling on for pages about the corners of conceptualism they prefer. The tongue-in-cheek reference in the exhibition title, Lowry and the Painting of Modern Life, didn’t help because it aligned the Mancunian to a story of modern art that doesn’t really apply to him – even the curators’ inspired casuistry couldn’t shoehorn a sui generis Lowry into any wider avant-garde narrative. Guys, Manet and Baudelaire are one thing, the experiences of a visually alert rent collector a lifetime afterwards quite another. That said, this is an excellent exhibition, intelligently, provocatively organized and with catalogue essays more elegantly written and thought through than the drivel customarily accompanying Tate advertisements for recent art. Even for those of us who met him and have often agonised over the real significance of his work, this exhibition helps us to see the Lowry phenomenon more clearly than ever we did before.

Lowry deserves treatment as a serious artist, though more usually such an approach is denied him because of, firstly, his suspiciously wide popularity and, secondly, what is mistakenly characterised as stylistic primitivism. A strong whiff of the patronizing informed reviews of this exhibition, as though the work was a tad unsophisticated for critics used to rambling on for pages about the corners of conceptualism they prefer. The tongue-in-cheek reference in the exhibition title, Lowry and the Painting of Modern Life, didn’t help because it aligned the Mancunian to a story of modern art that doesn’t really apply to him – even the curators’ inspired casuistry couldn’t shoehorn a sui generis Lowry into any wider avant-garde narrative. Guys, Manet and Baudelaire are one thing, the experiences of a visually alert rent collector a lifetime afterwards quite another. That said, this is an excellent exhibition, intelligently, provocatively organized and with catalogue essays more elegantly written and thought through than the drivel customarily accompanying Tate advertisements for recent art. Even for those of us who met him and have often agonised over the real significance of his work, this exhibition helps us to see the Lowry phenomenon more clearly than ever we did before.

Let’s put one fallacy to bed straightaway. If his pictures look hamfisted it was because he was happy for them to look that way. He knew exactly what he was saying with his style, was knowledgeable about events in both the art of his time and just before, and if his work appears mechanically simple then this was as deliberate as the simplifications and shortcuts informing much else in museum-approved Modern Art. His avoidance of clever-dick explanations when talking about his pictures, for example, is entirely refreshing in the context of unintelligible spoutings by the likes of the usual suspects.

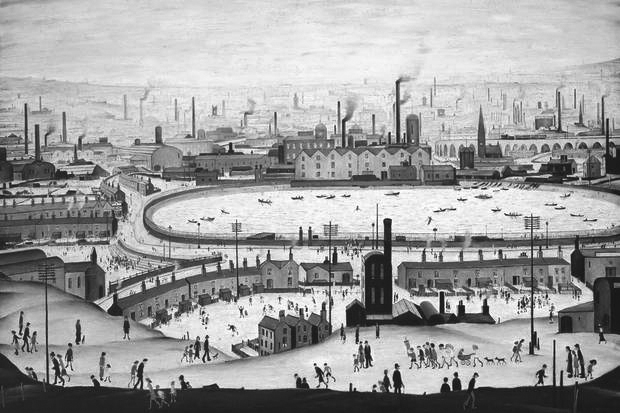

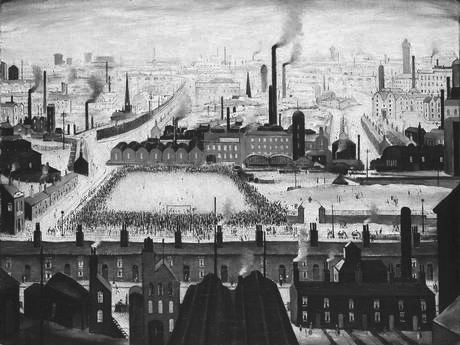

He attended art school for ten years, where he had a fine teacher whom he respected. Lowry’s personal solution to his own peculiar expressive needs arrived only slowly – as with Constable he was a late developer. And like many who discover an instantly identifiable personal idiom, he stuck to it because it worked, both for him and, more increasingly, for his rapidly developing and appreciative market. This ‘look’ said what he wanted and there is almost no stylistic development from first to last, except that as a pictorial formula it became tired and the execution slapdash. He must have been aware himself – perhaps even painfully – of this late tendency to self-parody. In the industrial scenes at least, his technique, brushwork and approach remained essentially unaltered for nearly fifty years. Painting conventional industrial landscapes, based on observation and spiced with a splash of ‘impressionism’, would not have spoken in the same way. In order to pack in the kaleidoscope of his observations he needed to invent and combine disparate elements, for his, more than most, is an imagined world inspired though it was by actual experience. The working class was for him amusing and impenetrable, a species apart to be observed with curiosity.

Like Stanley Spencer, Lowry realized from an early age that his subject was all around him. So what inspired this new style? It is tempting to attribute the reason to the fact that his teacher, Adolph Valette (1876-1942), painted the concentration of industry and suffocating air of Manchester and Salford in a way which must have seemed startling to those for whom city scenes were suspect subjects for serious art. Clearly Lowry realised that Valette had exposed the potential of a vital new subject, at least to his eyes. He might also have been aware of Pictorialist photographs by John Dudley Johnson (1868-1955) showing the gloomy effects of a century of industrial revolution on inner Manchester and Liverpool. Both these guides demonstrated that ugliness and filth might be redeemed by beauty of form. Is it too fanciful a suggestion that, as a rent man, Lowry trudged about the city with eyes awakened by his tutors to the unique shapes inflicted on open spaces by heavy and uncontrolled industrial development?

Lowry’s archetypal industrial ‘scene’ began to emerge around the First World War – a conflict in which he did not fight. From 1909 his family, though desperately aspiring to the middle class, lived modestly in Pendlebury, a working class suburb of north Salford overlooking the Irwell valley. As Ian Jack recently pointed out in the Guardian, this exact area was described by J B Priestley in English Journey in 1934 as having “an ugliness so complete that it is almost exhilarating … it challenges you to live there”.

Lowry was daily aware of this mesmerising, infernal panorama as soon as he opened his front door. Additionally, his duties as a rent collector introduced him to the sights of even more disadvantaged areas than his own. Just as Charles Dickens and Frank Holl toured the East End of London in pursuit of hard-hitting subjects, so Lowry walked the east of Manchester to observe the raw desolation of the other half. Even within the working class itself, Lowry’s beat of Harpurhey, Ancoats, Miles Platting, Beswick and Newton Heath were renowned as a cut below the rest. As late as the 1950s, and my own experience, these were still scarily impoverished places. Lowry’s view of ragged, hopeless, exhausted people is more accurate than quaint. Luckily for him, social life took place outdoors. Few were the cars and, whenever possible, children especially tended to live in the street in preference to their dark, damp houses. It was impossible to walk around Manchester in the 1950s and not notice cripples, the mad and utterly destitute who were prominent on virtually every street. No question there is a truth at the heart of Lowry’s vision.

He tried to paint with originality what he knew, but there is no trace of political motive or social criticism in what he describes. He merely watches, fascinated. Factories, gasometers, coolers, ginnels, long viaducts, cobbles, collieries, bird-cage bridges, back-street bookies, chimneys, churches and classical chapels, and mill blocks interspersed with the incidents of daily life; brawling, death, arguing, evictions, accident, toil and chronic need… These are the elements used by the outsider to orchestrate his scenes with their syncopated verticals tiptoeing across the picture. Each is a complete world in itself. And it’s always grey, weather-free, even on Bank Holiday Monday.

Immediately on entering the exhibition, you realize how draining and repetitive this all is, the mood unaltering, relentless. He painted the same picture with the same message in slightly different ways. And most of what comes after 1955 is the work of a retired, comfortable old gent with time on his hands. You also realise that the style doesn’t travel well. Specifics originated for one location look contrived when applied elsewhere. With few exceptions, perhaps a handful of scenes in Sunderland, his work depicting places outside Lancashire, is unsuccessful, the effect half-hearted. They reek of tourism, of holiday art, of unfelt work which didn’t need to be made. The panoramas of South Wales, for example, are failures for being half topography and half ‘style’. Even the considerable natural gift, apparently effortless, for achieving compositional balance deserts him in these scraps and oddities. A more selective artist would have destroyed them. If you lived in Lowryland and were fortunate to escape it for a few days, when you returned it instantly struck home that nowhere else, anywhere, looked anything like this particular place.

The exhibition shows us Lowry’s originality and his limitations. There is truth here, yes, about both the mental and physical conditions of the interwar populace, but it is hard to escape a conclusion that his descriptions, seen like this en masse, quickly arrive at decoration and formulaic pattern. Repeated mannerisms obstruct the emergence of something more profound from what was a horrifying subject.

David Lee