The State should be more circumspect than to behave like a private collector. Unfortunately, collecting and exhibiting in national collections according to narrow personal tastes and loyalties is established practice. Those employed to run Contemporary Art are selected because they have been carefully programmed in the tenets of State Art and if they have doubts keep quiet about them. But functionaries of State Art are not spending their own money and therefore in the policies governing collection and exhibition they should reflect the best from the full range that is being produced and not just follow those few desperately eking out the fag end of Opportunism. A damaging aspect of State Art has always been that it refuses to acknowledge anything outside its own narrow prejudices, which stop dead at those artists represented only by major art dealers and sold expensively in rigged markets by auction houses. Healthy dividing lines between museum curators and directors, auction houses and the most fashionable art dealers no longer exist. The system stinks worse than an open sewer, but many love the smell and wish to waft it over the rest of us so we might come to like it too.

State Art apostles all help one another in pursuance of their little ambitions. They are a happy club who play hard. Their governing Synod, which comprises all of those contributors to the unhealthy smell noted above, swarm off one week to Margate aboard the same train, the next week to Wakefield aboard the same train, days later they commune aboard the same flight to Venice, and the week after that they chink glasses again at the Basel Art Fair – it’s a hard life is State Art. Decisions made among themselves during these junkets will be imposed everywhere. What results from this process is the repeated exhibition of the same few artists. This keeps the rest of us in ignorance of so much that might otherwise have been stimulating. Most of my generation will never know what we have missed because we have lived our entire professional lives under a State Art regime administered by curators terrified to jeopardise their careers by thinking for themselves. Predictability being the worst of State Art’s crimes, we are never surprised.

Also like many of my generation, I suspect, I no longer feel the urge to see everything, having already viewed so much so often that hasn’t justified its hysterical praise by those with mysterious interests in promoting it. I’m sure Miro was a fascinating old cove but I’ve visited his studio in Palma and, to be honest, provided with a large enough mop and baths of black and the primaries, a toddler could produce in an afternoon most of the work on display there. Miro at the Tate? No thanks. Likewise Emin at the Hayward. Seen them before, and life is too short to indulge further the solipsism of an idiot. The problem for those of us with decades of exhibitions behind us is that this sort of material, the kind of thin work we are constantly exhorted to idolise, has become unavoidable. It gets everywhere. Nowhere is safe from it.

I recently visited the Orkneys for its birds and stones. Knowing that the Pier Arts Centre in Stromness held a donated collection of carefully selected minor works by important 20th century British artists, this was an early port of call. The permanent collection is the generous gift of Margaret Gardiner, who wrote an acclaimed biography of Barbara Hepworth and had an eye for quality which probably exceeded her modest purse. Nevertheless, she accumulated covetable, domestic-sized pieces by Hepworth, Moore, Nicholson, Piper, Heron, Frost, Lanyon and others, all of which will spark memories in knowledgeable viewers while touching those nerves and recesses where appreciation resides. The original gallery, at the heart of a busy harbour, has been done up courtesy of the Arts Council Lottery (£4 million) and there is now room for temporary displays and craftsy souvenirs. I was hoping to see here work by artists from north of Inverness and Aberdeen – the likes of Frances Walker for example – those whom one is unlikely to encounter elsewhere. No such luck. What they had on display were some scribbles and unsavoury looking skidmarks by Cy Twombly, of the ‘highly significant’ sort which cause State Art fanatics to collapse in a religious swoon, and a collection of inept portraits and even worse ‘landscapes’ by another fashionable and ludicrously expensive American artist, Alex Katz. (Twombly is represented by Larry Gagosian; Katz by Pace Wildenstein.) Both are described as ‘influential’. God help us, who with?

Katz’s portraits were trendily wooden, flat and unmodelled, the sitters characterless, boneless in some cases, and tediously stylised. Anyone whose eye has been nurtured by rich historical portraiture from Al Fayum and the Roman republic to Ravenna, Moroni, Rembrandt, Lawrence and Spencer couldn’t possibly see anything other than low-fat insipidity in Katz’s daubs. And his small landscapes, truly awful pictures, were so awkward and incompetent they were unworthy of hanging in a Women’s Institute. But no, they had been air-freighted 700 miles north of London for the benefit of Orcadians and those, like me, doggedly twitching for whimbrel and black guillemot. (Incidentally, en passant, the former you can more often hear than see and the latter, considerable rarities elsewhere on northern coasts, bobble about common as muck in Scapa Flow. Youalso ought to know about the corsair ravages of great skuas marauding in press gangs on Hoy – more engaging than either Twombly or Katz could ever be – but that’s for a different and probably a better magazine.) The presence of Katz in the northern isles wouldn’t have been quite so annoying had I not seen the same shallow gimmickry only a few months before, by accident note, in the National Portrait Gallery. I’d been bewildered then by what was officially considered to give this stuff precedence over works by effortlessly superior British portrait painters. Both Twombly and Katz are part of the Artists’ Rooms series which are enjoying a permanent tour of the country. This is the “generous gift”, by the way, for which we paid Anthony d’Offay £42 million. Artists’ Rooms, organised by the Tate, are the process, it would seem, by which nobody in the country will be safe from the tradenames of State Art. They are coming to a place near you whether you like it or not.

On the way south I didn’t stop for Jeff Koons at the Scottish National Gallery of Modern Art in Edinburgh (another Artist’s Room) having seen the trash he has to offer too many times before. I stopped instead at Wakefield where a £35 million museum (Arts Council Lottery: £5.5 million) designed by David Chipperfield has opened in honour of local artist Barbara Hepworth (1903-1975). This shed of grey slate, forbiddingly windowless for the most part, replaces the old Wakefield Art Gallery which was housed in the municipal Edwardian pile up the hill. Despite the beauty of a small number of masterpieces it contained, that was a gloomy, unloved place where, not surprisingly, few ventured. Despite its off-putting appearance, the new grey gallery is an improvement and stands beside an attractive weir (grey heron, grey wagtail) on the Calder 25 minutes walk from the railway station. Inevitably, the building has been overpraised by architecture scribblers. It is nothing at all remarkable, but is agreeable enough inside. Apart from the foyer, which is coloured in regulation Serota mud, the rest is white and spacious, the light a mixture of rationed natural and mains. The whole place is blighted by that self-inflicted virus of modern galleries and museums, patrolling attendants armed with squawking radios which destroy all attempts at uninterrupted concentration.

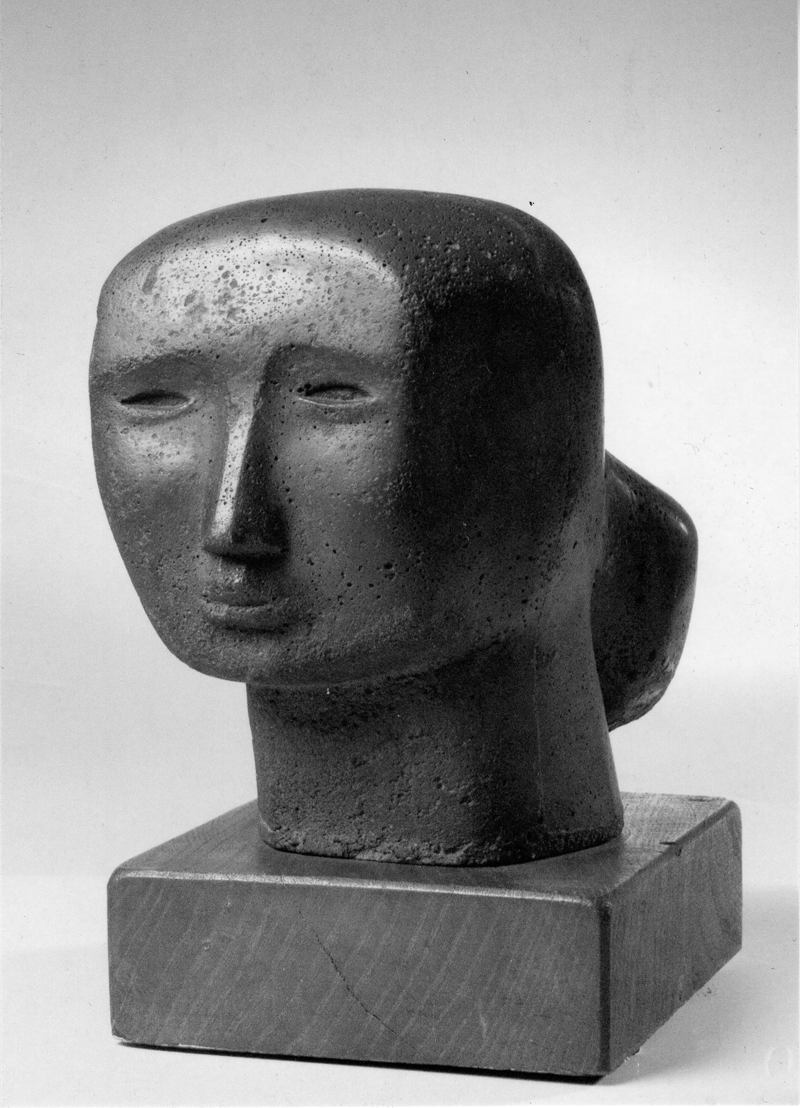

The historic Wakefield collection, mainly mid-century Modernism which is representative more than notable, is scarcely worth writing home about for anyone well acquainted with the field, but is augmented by apposite loans from elsewhere, mainly the Tate – a sensible use of their hidden reserves. From a loyalty point of view the display does Hepworth no favours. Gabo was more inventive in three dimensions with form, materials and especially string, while Moore, represented by two fine early sculptures, a reclining figure carved in writhing elm and the modelled cement head, render the nearby Hepworths stodgy and a bit simple. Her drawing of a surgical operation – these are usually her best things when seen reproduced small in books – looked vague next to one of Moore’s best shelter drawings. In this company Hepworth might be second rate but she’s still world famous in Wakefield.

Given that Arts Council money has gone in, they and their lieutenants, and particularly the dead hand of their State Art doctrine, are already calling the shots in the exhibition programme. The opening show is throwaway stuff. Doubtless during the selection process political correctness intervened something like this: we need a young female sculptor with impeccable State Art credentials, phone Serota. The chosen candidate was one Eva Rothschild, who is Irish. Fresh from the ponderous, overblown constructivism she served up last year at Tate Britain, she arrives here with playground materials and colours, inarticulate tangles of stuff on stands signifying heaven only knows what. Beside the humanist Hepworth this skip-fodder insults her memory.

Apart from Hepworth and Moore, think of the important contribution of Yorkshire to British sculpture in the last century – national figures like Kenneth Armitage, George Fullard, Austin Wright, Ralph Brown, Hubert Dalwood and all those gifted tutors and Gregory Fellowships at Leeds. The new museum had years to plan a retrospective of an important local sculptor, or a mixed show of work ripe for reassessment, but instead they present scraps by yet another over-exhibited fashionable novice with no discernible sculptural ability. As usual with the Arts Council, their programming is a lazy failure.

Needless to say the Council’s finest snake oil salesmen have been scratching their heads over Rothschild. Following months of screwed up paper they cobbled together this salvo of lucidity: “This exploration of the intrinsic power and meanings carried by objects produced a transformational encounter between the animal forms and the symbolic and narrative potential of Rothschild’s work.” One of these days, soon I hope, they will realise they are communicating with fellow humans. But the Arts Council don’t do editing or clarity, and neither is conciseness in their lexicon: “There is a playful defiance of gravity and materiality in many of these sculptures that probe, test and occupy the gallery space.” Probe, test, occupy the gallery space … No, you’ve got me there. Perhaps the good folk of Cleckheaton and Goole are fluent in this guff, but I doubt it.

David Lee

The Jackdaw Jul-Aug 2011