Edward Lucie-Smith admires an ambitious exhibition but with the reservation that something is missing

The big new exhibition of Matisse’s Cut-Outs at Tate Modern in London is, certainly on the face of it, everything that a major museum of Modern and Contemporary Art should be doing. It is beautifully presented, very professionally curated, has an extremely thorough, excellently illustrated catalogue and has been greeted with ecstatic reviews. It is thronged with visitors, but fortunately not to the point of suffocation (as was the case, alas, with the National Gallery’s recent Leonardo da Vinci exhibition). The rooms in which it is shown are big enough to allow the visitor enough space to view the exhibits from a variety of distances, and the works themselves are often on a suitably grand scale.

The big new exhibition of Matisse’s Cut-Outs at Tate Modern in London is, certainly on the face of it, everything that a major museum of Modern and Contemporary Art should be doing. It is beautifully presented, very professionally curated, has an extremely thorough, excellently illustrated catalogue and has been greeted with ecstatic reviews. It is thronged with visitors, but fortunately not to the point of suffocation (as was the case, alas, with the National Gallery’s recent Leonardo da Vinci exhibition). The rooms in which it is shown are big enough to allow the visitor enough space to view the exhibits from a variety of distances, and the works themselves are often on a suitably grand scale.

I departed from it thinking that here was exactly the kind of show that an institution of this kind ought to present. Tate Modern is, currently, the most visited gallery of modern art in the world, outstripping both the Museum of Modern Art in New York and the Pompidou in Paris, although, to be frank, its own permanent collection is not on a par with the stellar holdings of either of these rivals. It was only after I left that doubts began to make themselves felt, and I’m not sure that these doubts are the fault of Tate Modern or of the organizers of the occasion. Perhaps they are inherent in our present cultural situation, where the creative force of the Modern Movement seems to be inexorably dwindling away.

Just over 113 years ago, in November 1910, the Grafton Galleries in London opened a show called Manet and the Post-Impressionists. It was apparently the first time that the term ‘Post-Impressionist’ was used in English. Matisse, who had sprung to fame at the Paris Salon des Indépendants of 1905, was one of the artists included. The British press was excoriating about the exhibition. The anonymous reviewer in The Times of London commented that the work shown “throws away all that the long-developed skills of past artists had acquired and bequeathed. It begins all over again – and stops where a child would stop.” How times have changed!

Yet it is immediately obvious that in some respects Matisse’s work during his last years did not move very far from what was shown in Paris in 1905 and in 1910 and in London. The famous Luxe, calme et volupté, shown at the Indépendants in 1905, and now in the collection of the Musée d’Orsay in Paris, is a very recognizable ancestor of the compositions with nudes shown in London.

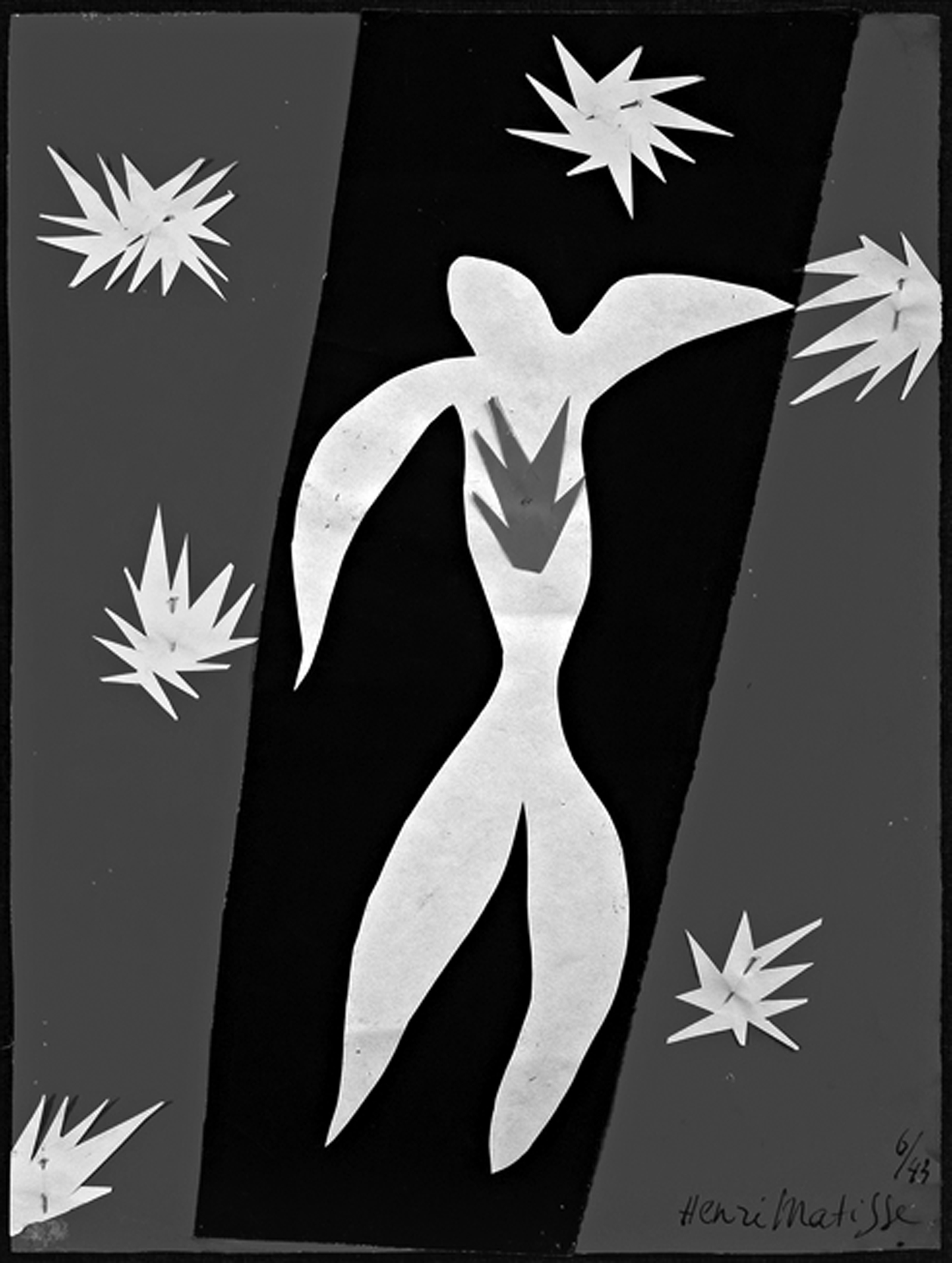

What changed was the technique. The compositions were no longer painted, they were made with pieces of cut paper. Matisse did the cutting, and the papers he used were painted in gouache to his exact specifications. Once cut, they were pinned in place according to his directions.

Matisse had already experimented with designs made from cut and pasted paper in the 1930s – the projects he tackled included decors for the ballet and maquettes for book covers. When he did these collage was already long established as one of the typically ‘modernist’ methods of image making. Picasso and other Cubists had made radically experimental use of it. Collage techniques had also been extensively employed by amateur artists throughout the 19th century. Interestingly the word ‘collage’ seems to be absent from the catalogue. Matisse was not completely an innovator in this phase of his work.

The real starting point for the Cut-Outs was the serious illness that Matisse suffered from in 1941. He was operated on for duodenal cancer and nearly died from resultant complications. As a result he was unable to stand up for long periods, and had to make art while seated in a wheel chair, from another specially adapted chair, or reclining in his bed. Using scissors and cut paper he could, with the help of assistants, continue to create work on an ambitious scale.

Because of Matisse’s long-established celebrity the process of making these works and the various stages they went through were extensively documented photographically. The catalogue published in connection with the current Tate Modern exhibition has a very rich series of illustrations of this kind, made by various photographers, some working under the artist’s direction, and some not.

If one reads the Tate catalogue attentively, it is possible to detect a certain note of nostalgic regret that appears when these records of the images in situ in Matisse’s several studios are discussed. What the authors of the various essays seem to long for is permission to hail Matisse as the pioneer, perhaps even the God the Father, of the current Post Modernist tendency to promote installation as the pinnacle or ne plus ultra of late Modernist and Post-Modernist creativity. The problem is that they can’t quite bring themselves to say this in so many words. As it happens, their silence is justified by what one actually sees at the Tate.

Wonderfully decorative as many of them are, it is clear that a certain loss of freshness took place when the Cut-Outs were removed from Matisse’s studio and made ready for public exhibition. All too often, one feels as if one is looking at an exquisitely beautiful, immaculately preserved corpse. There is another problem as well. The aged Matisse, armed with a pair of scissors, confidently slicing through the sheets of coloured paper prepared for him, was wonderfully skilful at simplifying natural forms – nude female bodies, birds, fish, leaves, even algae floating in water. Yet the compositions only occasionally add up to something more than decoration. Some extra dimension of emotion is missing.

Towards the end of the presentation there is something not technically a Cut-Out – a stained glass window called Christmas Eve, commissioned by Time Inc. in New York. The composition is curiously perfunctory – banal symbolism for a safely ecumenical Christmas card.

Despite the fame of the Matisse-designed chapel at Vence – maquettes for its windows are also included in the show – religious emotion was clearly not part of Matisse’s temperament. With this exhibition ‘What you see is what you get’. Exactly what you get – don’t ask for more. I left thinking it was 99% wonderful, and regretting the missing one per cent perhaps more than I should have done.