Edward Lucie-Smith charts the decline of contemporary art from Modernism and the avant garde to being a mere epiphenomenon of the fashion industry

Ten days or so ago, before beginning to write this, I was idly browsing a slightly out-of-date copy of the Evening Standard Magazine. Anything to avoid the toil of having to write something myself. Faute de mieux, my eye fell on a piece that was ostensibly about the demise of the so-called ‘It-Bag’ – something about as far from my own usual range of interests as one can conveniently get.

Ten days or so ago, before beginning to write this, I was idly browsing a slightly out-of-date copy of the Evening Standard Magazine. Anything to avoid the toil of having to write something myself. Faute de mieux, my eye fell on a piece that was ostensibly about the demise of the so-called ‘It-Bag’ – something about as far from my own usual range of interests as one can conveniently get.

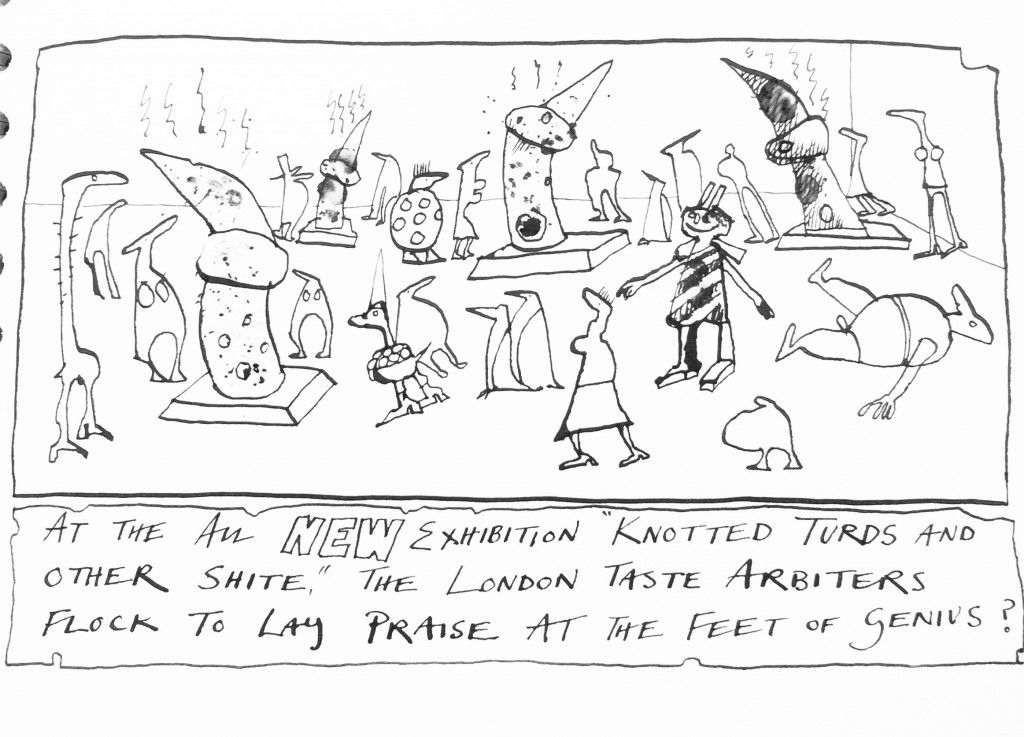

It began as follows: “As I navigated the giant Carsten Holler mushroom sculptures and the sleeping security guard who may or may not have been a work of art at the VIP preview of Frieze art fair earlier this month, my focus drifted from the exhibits to the people standing studiously in front of them. Take away the art and you’d be forgiven for thinking you were at London Fashion Week – every turn revealed a glossy gallerist or collector with a Céline coat draped over her shoulders, power-walking the halls in Chanel trainers. There’s a reason that Alexander McQueen and Gucci are both sponsors of the fair. Designer stores report bigger sales during Frieze week than at any other time of year (even Christmas). Now in its 11th year, Frieze has evolved into and unbeatable style barometer.”

This paragraph crystallized a thought that had been already hovering in my mind for some time. The fact is that there is no real visual arts avant-garde any more, despite all the strenuous efforts being made by those who see themselves as the guardians and prophets of contemporary culture to persuade us to the contrary.

Serendipity has it that The Museum of Modern Art in New York is currently celebrating the activity of a woman artist, previously unknown to me, who worked under the name of Sturtevant (American 1924-2014). The MOMA press release proclaims that this retrospective show “identifi[es] her as a pioneering and pivotal figure in the history of modern and post modern art.”

What did Sturtevant do? Essentially she made versions of works by better-known artists who were her contemporaries – Johns, Warhol, Lichtenstein, Gonzalez-Torres, Keith Haring and Anselm Kiefer among others. MOMA celebrates this process as follows:

“Though her “repetitions” may appear to be simply mimetic exercises in proto-appropriation, Sturtevant is better understood as an artist who adopted style as her medium and took the art of her time as a loose score to be enacted and reinterpreted. Far more than mere copies, her versions of Johns’s flags, Warhol’s flowers, and Joseph Beuys’s fat chair are studies in the action of art that expose aspects of its making, reception, circulation, and canonization.”

It would be hard to devise a more comprehensive and emphatic endorsement of today’s mandarin culture.

The fashonistas and the mandarins are allied. What they promote is a kind of art that assumes the trappings of ‘traditional avant-gardism’ (an oxymoron if ever there was one), but which in fact runs away from real innovation just as fast at its pattering little paws will carry it.

A process of this kind is not entirely new. If one looks at Chinese literati culture for example, one sees how Chinese ink painting ossified, after the fall of the Ming dynasty, into endless paraphrases of older masters. What counted was not the image actually created, but the nuances of style, the echoes of what had gone before.

What the MOMA statement quoted above assumes is that the ideal spectator will already be immersed in the previous history of ‘approved’ avant-garde art. He or she will be able to read, not only the actual text presented, but also the sub-text that lies beneath it. It is, for instance, noticeable that the numerous artists Sturtevant has chosen to paraphrase have no stylistic relationship. What they do have in common is, yes, their gender (Sturtevant is taking them on as the champion of her sex), but also, and perhaps more importantly, their celebrity – the fact that they are all famous and, what is more, famous in a characteristically contemporary way, certified by mechanisms of publicity that came into existence only recently.

The challenge offered to the lay person is not the one originally offered by the Modern Movement, as it existed during the first seven decades or so of the last century. That challenge was: “Allow your mind and your sensibility to be opened to something entirely new, unthought of in all the previous centuries of culture.” Now the lay person is asked a different question: “Are you one of us or one of them? Chav or non-chav? Elite or hoi-polloi? If you want to be on-message, you’d better step up quick and join us.”

Responses to this challenge are further complicated by the degree to which what is supposedly avant-garde has become embedded in the mechanisms of today’s official culture.

This culture, in the western European democracies at least, and also (with certain nuances) in the United States, is determined to be popular. It is supported with large sums of public money, and must therefore reach out as directly as possible to as many people as possible. Hence much of the recent emphasis on what is both immediate and ephemeral, qualities encapsulated in performance art. The alliance between supposedly traditional forms of expression, such as painting and sculpture, and performance is in fact much older than enthusiasts for the radically contemporary are prepared to admit. One thinks of the Dance of Death performances held in churchyards during the Middle Ages, which only somewhat later found a more permanent form, as sequences of prints – a form which, of course, had to wait for the invention of the printing press.

Throughout the Middle Ages the more ambitious expressions of the visual arts were more usually than not addressed to a mass public, not simply to an elite, though they relied on elite patronage. The reason for this was their link to a universal faith. The bedrock was a common system of beliefs.

To a limited extent, one must admit, things have now come full circle. The supposedly avant-garde visual arts are placed before an audience of every taxpayer, just as the sacred art of the Middle Ages was made accessible to every worshipper. This offers a telling contrast to the private, conspiratorial rituals of the early years of the Modern Movement, when experimental art was in retreat, both voluntarily and involuntarily, from the glare of publicity offered by the official Salons of the same epoch. In fact, it was the brutally hostile Entartete Kunst exhibition organized by the Nazi regime in Munich in 1937 that finally brought Modernism in art to a wider public. One million people attended the show in the course of its first six weeks. It is safe to guess that the attendees represented a much wider social spread, in terms of both class and education, than any audience Modernist work had attracted previously.

What is different now, from the situation in the Christian Middle Ages, is the lack of a secure, firmly held belief system about what art is, and what it is supposed to do within the social context. We still, however, retain a curious, atavistic attachment to the idea that art is a charismatic product, with a mysterious impact on our psyches. Very often, we now transfer this belief from the object to the personality responsible for producing the object. This has been developed to the point where celebrated artists are regarded as the equivalents of primitive shamans – Joseph Beuys and, more recently, Marina Abramovic are cases in point.

This lack of a belief system has had a powerful and often catastrophic impact on public art. For example, even now we instinctively expect public sculptures to convey some kind of message, other than a purely aesthetic one. Yet the message, in new monuments of this kind, commonly seems so shallow and clichéd that it doesn’t have any effect. Purely abstract public sculptures – ‘art about art’ – usually fail even more catastrophically. They become simply large-scale open-air ornaments, pretty enough in their way, but with little, or even no, emotional impact. Hence the appearance, in common parlance, of the derogatory term “plop sculpture”, implying that the artwork in question is not much higher in status than a giant dog turd.

It is notable, in this connection, that the one public image, here in Britain, that did quite recently move and energize a mass audience was the huge display of ceramic poppies, temporarily planted in the moat of the venerable Tower of London to commemorate the dead of World War I. The project was created by two relative unknowns – a ceramic artist working with a theatrical set designer. Part of its point was that it was intentionally ephemeral.

Now that Modernism has apparently run its course, and when the sequence of identifiable Modernist art movements has reached a full stop, we are confronted with a situation in which the art of our own times seems directionless. Attempts to define its salient qualities rely very largely on negative formulations. It is Post Modern. Or Post Post Modern. Or even (in desperation) Post Pop. It often relies heavily on Appropriation – self-consciously copying pre-existing art, stressing its own lack of original invention – in order to make its points.

The characteristic art of our time also tends to rely very heavily on context. If we encounter a particular object, group of objects or event in a place where we expect to see art, such as in a museum, a contemporary gallery, or at an art fair, then – sure enough, art it is: the context guarantees it. If the place where we encounter it isn’t defined as a space for art, our reactions are not triggered in the same fashion.

There is also the fact that the knee-jerk reactions that the pioneer Modernists relied on to make their points for them are harder and harder to evoke. The same buttons have been pushed too often.

Basically once art loosened its age-old ties with religion, and at the same time increasingly ceased to be credibly involved in the celebration of wealth and power, it relied increasingly on being contrarian – on telling its audience things it didn’t necessarily want to hear. Uproar, and frantic opposition to the message, were the first steps towards eventual acceptance and celebrity. If one looks at the development of the 20th century avant gardes (in the plural), one sees that this was largely cyclic. A tendency or style or set of aesthetic ideas established itself after a period of struggle. As soon as the sandcastle was fully built, however, a wave came racing up the beach to overthrow it. It is amusing in retrospect to note how furiously the reigning critics and theoreticians who established the dominance of Abstract Impressionism opposed the rise of Pop Art.

In crude terms, controversies about art, since the birth of the Modern Movement, have relied on four things. The two most fundamental were, first, the insistence that the world could be seen in new ways – that the established processes whereby what the artist saw could be translated to make an art work that other people were going to see could be radically re-jigged. Secondly, linked to this, but not entirely identified with it, there was the idea that art could be its own subject, entirely self-reflexive. Neither of those impulses seems to be in any way dominant in the art world we now have, though the fashion for Appropriation shows maybe some last, distorted traces of the doctrine of art for art’s sake.

The third and fourth impulses were cruder. Art threw itself into politics, and it became increasingly candid about sex.

The political impulse goes a long way back. It began at least a century before the rise of the Modern Movement. One can trace its trajectory from the political masterpieces of J-L David (Marat Assassiné) and Delacroix (The Massacre at Chios) to, perhaps, Picasso’s Guernica. Now it seems to have lost pretty well all of its impetus. The Disobedient Objects show, currently on view at the V & A, offers a classic instance of preaching to the converted.

Much the same things can be said about aggressive eroticism. The erotic impulse has been present in art ever since men began to make art. In the 20th century, erotic representations and brutally obvious erotic allusions became one of the ways through which artists tried to trademark their work as being ‘radical’ – something opposed to the social conventions of their time. This endured till comparatively recently. Remember those Chapman Brothers figures in the R.A.’s Sensation! show of 1997, with penises for noses? Remember – also from the 1990s – Jeff Koons’ sculptures of himself screwing his then-wife, the Italian porn-star La Cicciolina? You can still find one or two of them on the Web, if you care to look.

All that seems to be over. Shock tactics no longer shock. Avant-garde art has been gobbled up by the fashion world, and by today’s celebrity culture. What’s it for? It’s for posing in front of, wearing a nice frock. It quotes, daintily, from the avant-garde styles that entertained and enlightened us in the past, but as for trying to change the world – “Have another caviar canapé, darling – all that stuff seems sooo boring now.”

The triumph of avant-garde lite

Edward Lucie-Smith charts the decline of contemporary art from Modernism and the avant garde to being a mere epiphenomenon of the fashion industry

It began as follows: “As I navigated the giant Carsten Holler mushroom sculptures and the sleeping security guard who may or may not have been a work of art at the VIP preview of Frieze art fair earlier this month, my focus drifted from the exhibits to the people standing studiously in front of them. Take away the art and you’d be forgiven for thinking you were at London Fashion Week – every turn revealed a glossy gallerist or collector with a Céline coat draped over her shoulders, power-walking the halls in Chanel trainers. There’s a reason that Alexander McQueen and Gucci are both sponsors of the fair. Designer stores report bigger sales during Frieze week than at any other time of year (even Christmas). Now in its 11th year, Frieze has evolved into and unbeatable style barometer.”

This paragraph crystallized a thought that had been already hovering in my mind for some time. The fact is that there is no real visual arts avant-garde any more, despite all the strenuous efforts being made by those who see themselves as the guardians and prophets of contemporary culture to persuade us to the contrary.

Serendipity has it that The Museum of Modern Art in New York is currently celebrating the activity of a woman artist, previously unknown to me, who worked under the name of Sturtevant (American 1924-2014). The MOMA press release proclaims that this retrospective show “identifi[es] her as a pioneering and pivotal figure in the history of modern and post modern art.”

What did Sturtevant do? Essentially she made versions of works by better-known artists who were her contemporaries – Johns, Warhol, Lichtenstein, Gonzalez-Torres, Keith Haring and Anselm Kiefer among others. MOMA celebrates this process as follows:

“Though her “repetitions” may appear to be simply mimetic exercises in proto-appropriation, Sturtevant is better understood as an artist who adopted style as her medium and took the art of her time as a loose score to be enacted and reinterpreted. Far more than mere copies, her versions of Johns’s flags, Warhol’s flowers, and Joseph Beuys’s fat chair are studies in the action of art that expose aspects of its making, reception, circulation, and canonization.”

It would be hard to devise a more comprehensive and emphatic endorsement of today’s mandarin culture.

The fashonistas and the mandarins are allied. What they promote is a kind of art that assumes the trappings of ‘traditional avant-gardism’ (an oxymoron if ever there was one), but which in fact runs away from real innovation just as fast at its pattering little paws will carry it.

A process of this kind is not entirely new. If one looks at Chinese literati culture for example, one sees how Chinese ink painting ossified, after the fall of the Ming dynasty, into endless paraphrases of older masters. What counted was not the image actually created, but the nuances of style, the echoes of what had gone before.

What the MOMA statement quoted above assumes is that the ideal spectator will already be immersed in the previous history of ‘approved’ avant-garde art. He or she will be able to read, not only the actual text presented, but also the sub-text that lies beneath it. It is, for instance, noticeable that the numerous artists Sturtevant has chosen to paraphrase have no stylistic relationship. What they do have in common is, yes, their gender (Sturtevant is taking them on as the champion of her sex), but also, and perhaps more importantly, their celebrity – the fact that they are all famous and, what is more, famous in a characteristically contemporary way, certified by mechanisms of publicity that came into existence only recently.

The challenge offered to the lay person is not the one originally offered by the Modern Movement, as it existed during the first seven decades or so of the last century. That challenge was: “Allow your mind and your sensibility to be opened to something entirely new, unthought of in all the previous centuries of culture.” Now the lay person is asked a different question: “Are you one of us or one of them? Chav or non-chav? Elite or hoi-polloi? If you want to be on-message, you’d better step up quick and join us.”

Responses to this challenge are further complicated by the degree to which what is supposedly avant-garde has become embedded in the mechanisms of today’s official culture.

This culture, in the western European democracies at least, and also (with certain nuances) in the United States, is determined to be popular. It is supported with large sums of public money, and must therefore reach out as directly as possible to as many people as possible. Hence much of the recent emphasis on what is both immediate and ephemeral, qualities encapsulated in performance art. The alliance between supposedly traditional forms of expression, such as painting and sculpture, and performance is in fact much older than enthusiasts for the radically contemporary are prepared to admit. One thinks of the Dance of Death performances held in churchyards during the Middle Ages, which only somewhat later found a more permanent form, as sequences of prints – a form which, of course, had to wait for the invention of the printing press.

Throughout the Middle Ages the more ambitious expressions of the visual arts were more usually than not addressed to a mass public, not simply to an elite, though they relied on elite patronage. The reason for this was their link to a universal faith. The bedrock was a common system of beliefs.

To a limited extent, one must admit, things have now come full circle. The supposedly avant-garde visual arts are placed before an audience of every taxpayer, just as the sacred art of the Middle Ages was made accessible to every worshipper. This offers a telling contrast to the private, conspiratorial rituals of the early years of the Modern Movement, when experimental art was in retreat, both voluntarily and involuntarily, from the glare of publicity offered by the official Salons of the same epoch. In fact, it was the brutally hostile Entartete Kunst exhibition organized by the Nazi regime in Munich in 1937 that finally brought Modernism in art to a wider public. One million people attended the show in the course of its first six weeks. It is safe to guess that the attendees represented a much wider social spread, in terms of both class and education, than any audience Modernist work had attracted previously.

What is different now, from the situation in the Christian Middle Ages, is the lack of a secure, firmly held belief system about what art is, and what it is supposed to do within the social context. We still, however, retain a curious, atavistic attachment to the idea that art is a charismatic product, with a mysterious impact on our psyches. Very often, we now transfer this belief from the object to the personality responsible for producing the object. This has been developed to the point where celebrated artists are regarded as the equivalents of primitive shamans – Joseph Beuys and, more recently, Marina Abramovic are cases in point.

This lack of a belief system has had a powerful and often catastrophic impact on public art. For example, even now we instinctively expect public sculptures to convey some kind of message, other than a purely aesthetic one. Yet the message, in new monuments of this kind, commonly seems so shallow and clichéd that it doesn’t have any effect. Purely abstract public sculptures – ‘art about art’ – usually fail even more catastrophically. They become simply large-scale open-air ornaments, pretty enough in their way, but with little, or even no, emotional impact. Hence the appearance, in common parlance, of the derogatory term “plop sculpture”, implying that the artwork in question is not much higher in status than a giant dog turd.

It is notable, in this connection, that the one public image, here in Britain, that did quite recently move and energize a mass audience was the huge display of ceramic poppies, temporarily planted in the moat of the venerable Tower of London to commemorate the dead of World War I. The project was created by two relative unknowns – a ceramic artist working with a theatrical set designer. Part of its point was that it was intentionally ephemeral.

Now that Modernism has apparently run its course, and when the sequence of identifiable Modernist art movements has reached a full stop, we are confronted with a situation in which the art of our own times seems directionless. Attempts to define its salient qualities rely very largely on negative formulations. It is Post Modern. Or Post Post Modern. Or even (in desperation) Post Pop. It often relies heavily on Appropriation – self-consciously copying pre-existing art, stressing its own lack of original invention – in order to make its points.

The characteristic art of our time also tends to rely very heavily on context. If we encounter a particular object, group of objects or event in a place where we expect to see art, such as in a museum, a contemporary gallery, or at an art fair, then – sure enough, art it is: the context guarantees it. If the place where we encounter it isn’t defined as a space for art, our reactions are not triggered in the same fashion.

There is also the fact that the knee-jerk reactions that the pioneer Modernists relied on to make their points for them are harder and harder to evoke. The same buttons have been pushed too often.

Basically once art loosened its age-old ties with religion, and at the same time increasingly ceased to be credibly involved in the celebration of wealth and power, it relied increasingly on being contrarian – on telling its audience things it didn’t necessarily want to hear. Uproar, and frantic opposition to the message, were the first steps towards eventual acceptance and celebrity. If one looks at the development of the 20th century avant gardes (in the plural), one sees that this was largely cyclic. A tendency or style or set of aesthetic ideas established itself after a period of struggle. As soon as the sandcastle was fully built, however, a wave came racing up the beach to overthrow it. It is amusing in retrospect to note how furiously the reigning critics and theoreticians who established the dominance of Abstract Impressionism opposed the rise of Pop Art.

In crude terms, controversies about art, since the birth of the Modern Movement, have relied on four things. The two most fundamental were, first, the insistence that the world could be seen in new ways – that the established processes whereby what the artist saw could be translated to make an art work that other people were going to see could be radically re-jigged. Secondly, linked to this, but not entirely identified with it, there was the idea that art could be its own subject, entirely self-reflexive. Neither of those impulses seems to be in any way dominant in the art world we now have, though the fashion for Appropriation shows maybe some last, distorted traces of the doctrine of art for art’s sake.

The third and fourth impulses were cruder. Art threw itself into politics, and it became increasingly candid about sex.

The political impulse goes a long way back. It began at least a century before the rise of the Modern Movement. One can trace its trajectory from the political masterpieces of J-L David (Marat Assassiné) and Delacroix (The Massacre at Chios) to, perhaps, Picasso’s Guernica. Now it seems to have lost pretty well all of its impetus. The Disobedient Objects show, currently on view at the V & A, offers a classic instance of preaching to the converted.

Much the same things can be said about aggressive eroticism. The erotic impulse has been present in art ever since men began to make art. In the 20th century, erotic representations and brutally obvious erotic allusions became one of the ways through which artists tried to trademark their work as being ‘radical’ – something opposed to the social conventions of their time. This endured till comparatively recently. Remember those Chapman Brothers figures in the R.A.’s Sensation! show of 1997, with penises for noses? Remember – also from the 1990s – Jeff Koons’ sculptures of himself screwing his then-wife, the Italian porn-star La Cicciolina? You can still find one or two of them on the Web, if you care to look.

All that seems to be over. Shock tactics no longer shock. Avant-garde art has been gobbled up by the fashion world, and by today’s celebrity culture. What’s it for? It’s for posing in front of, wearing a nice frock. It quotes, daintily, from the avant-garde styles that entertained and enlightened us in the past, but as for trying to change the world – “Have another caviar canapé, darling – all that stuff seems sooo boring now.”

Share: