Anthony Daniels visits a degree show at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

Anthony Daniels visits a degree show at the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts in Paris.

I am in blood

Stepped in so far that, should I wade no more,

Returning were as tedious as go o’er.

Macbeth, Act 3 scene iv

No one would have understood better than Macbeth the logic of the inexorable destruction by the art education establishment of artistic tradition, and thereby the value of practically all subsequent artistic production. The process must continue, or those who were and are responsible for it must admit their guilt and lose their jobs. Their livelihoods, if not their lives, are at stake. Therefore that establishment must continue to see worth in worthlessness and deep significance in the utterly trivial, and to persuade the public that if it does not do likewise the fault lies with its own lack of sophistication and powers of discrimination. The art education establishment draws aid and comfort from the following quasi-syllogism taken from art history, the kind of vulgate that is now, alas, familiar to every art student:

Van Gogh was not understood in his lifetime and sold not a single painting to the public. Van Gogh was a great painter. His story was typical of art history down the ages. Artists X, Y, and Z are not understood and the public neither appreciates nor buys their work. Therefore artists X, Y, and Z are great artists like Van Gogh.

The errors both empirical and logical in this syllogism hardly need pointing out; but it haunts the mind of many of those who teach art, and probably the minds of many critics too. To miss the next Van Gogh! To be quoted in the future only as the man or woman who saw nothing in Van Gogh! That fate does not await those who extol art in which subsequent generations take no interest and see no merit. Their vaticinations are merely forgotten rather than ridiculed; and it is better to be forgotten than held up to ridicule. They therefore take Pascal’s bet with regard to current artists, however worthless they may secretly think, or even know, their work to be.

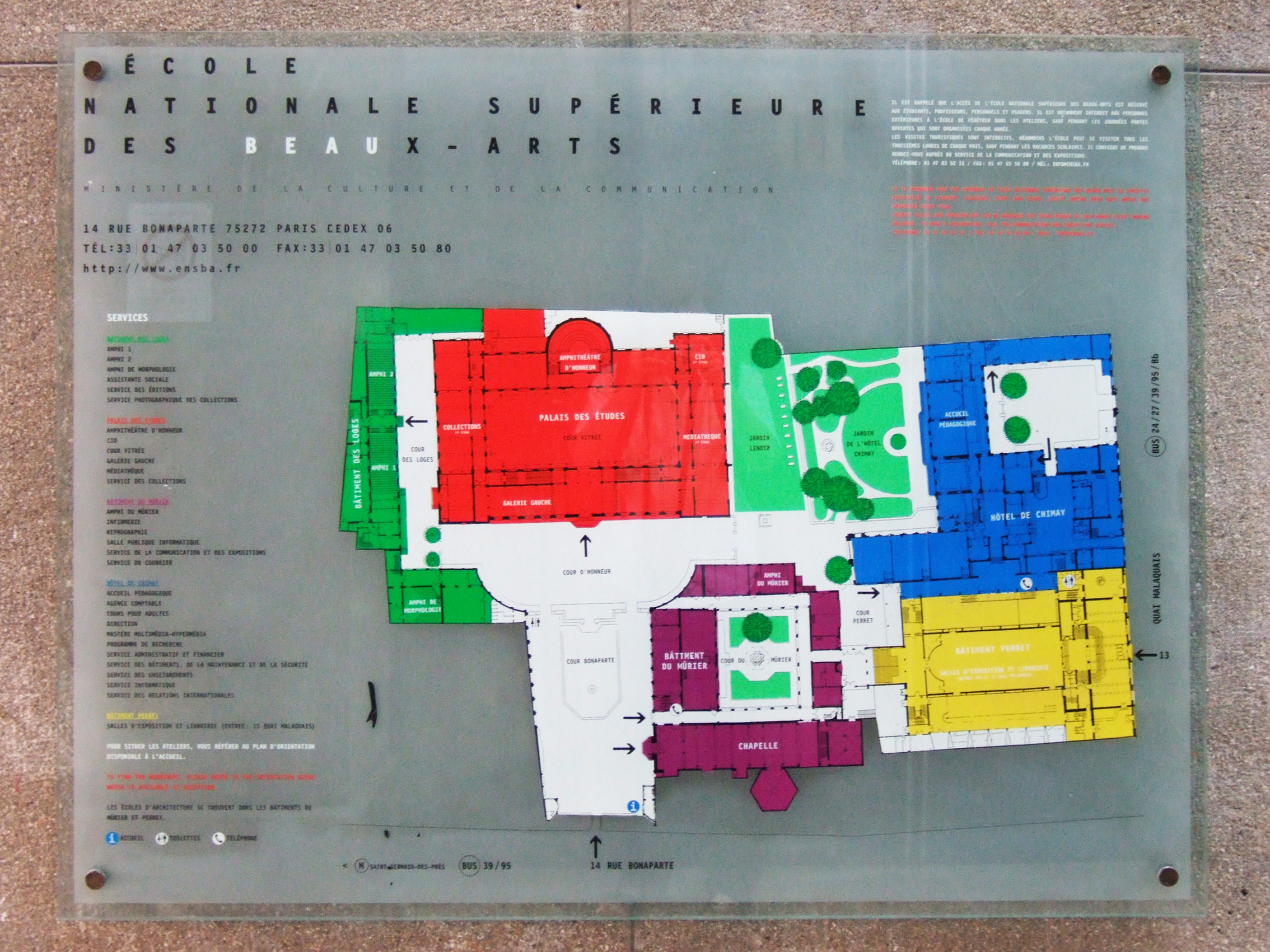

In Paris recently I went to see an exhibition of the work of graduates of the École Nationale Supérieure des Beaux-Arts, selected by a jury for its special merit. Had the process that has turned practically all British art schools into kindergartens for the ambitious but untalented (except in the most fundamental art of our time, self-promotion) occurred across the Channel? Called Possibles d’un monde fragmenté, even the rather curious syntax of the title aroused my apprehensions – and in a sense I was not to be disappointed. The exhibition was precisely what I thought it was going to be, a tiresome extension of Duchamp’s joke taken au sérieux more than a century later. I doubt that any joke in the history of the world has had a longer life or a more disastrous effect than Duchamp’s.

To judge by my visit, the Parisian public voted with its feet and stayed away, even though entry to the exhibition was free of charge. It was not that that public had lost its taste for art, far from it; you had to queue (as well as pay) to get into Perugino at the Musée Jacquemart-André, for example, or the seasons in Japanese art at the Musée Cernuschi. A public that is open to such widely different artistic traditions is not bigoted, uninformed or undiscriminating; it is simply uninterested in the cheap trash, for the close examination of which life is far too short.

To describe the exhibits – the various scraps of rag, bits of wood, video clips, piles of various objects, bits of twisted metal, empty spaces, dirty polythene stretched out on three-dimensional frames, scraps of paper scribbled on and so forth, oh God how tedious! – would be to do them far too much honour. It still astonished me, though probably it should not have done, that these ‘projects’, as the young ‘artists’ insisted on calling their productions, were the fruit of five years’ ‘study’ after having left school, study in what the director of the École Nationale, in his introduction to the catalogue, called, apparently without irony and certainly without self-knowledge, ‘one of the last havens of the classical humanities’. The few paintings, in what no doubt the director would have called ‘the classical humanist tradition’, gave a clear indication of an inadequate technical mastery and therefore of training. Whether the students entered the École with any God-given talent, and therefore whether the director was a true corruptor of youth, it was impossible from these paintings to say; but their minds had been so filled with intellectual junk that the more they thought, the worse things got.

The jury claimed modestly that it did not select the 19 félicités among the 87 graduates of the school on any principle, aesthetic or intellectual, other than a coup de coeur occasioned by their works: but what kind of heart could be moved by, for example, a photograph in lurid, vulgar colours of a woman’s finger with painted fingernail pressing on a cancel button of an electric toaster to make two pieces of industrially-sliced toasted bread pop up? Indeed, if such a work could occasion a coup de coeur, what must the emotional content be of the work of the 68 graduates not selected for special approbation?

That it should come to this in a city as richly saturated with art as any in the world! Could there have been more eloquent testimony to our civilizational exhaustion, at least as far as fine art is concerned, than this exhibition of the félicités of the Beaux-Arts? Surrounded by incomparable artistic wealth, the félicités produced the kind of grubby and depressing bric-à-brac that any reasonably conscientious femme de ménage would feel ashamed not to clear away or at least to cover up when visitors were expected. O originality, what crimes are committed in thy name!

Not that the young artists are free of ideas, far from it, alas. Their brains are fairly buzzing with ideas, or rather with the simulacra of ideas. There are interviews with them in the catalogue that accompany the illustrations of their work, conducted by art critics who speak a kind of portentous hermetic language: ‘How does your approach fit in with the inheritance of the institutional critique of the 1960s and 70s, which aimed to critique the authority systems of contemporary art?’ or ‘The recurring problematic of these pieces is spatio-temporality and the notion of outer limits.’

Notwithstanding the ‘problematic of spatio-temporality,’ the cultural references of the artists seem rather restricted in time, the 1960s being almost prehistoric for them, of the same era, more or less, as the Lascaux cave paintings. And many of them seem to suffer from science-envy, as if art were of no real social, intellectual or cultural significance nowadays, the action, as it were, being nowadays all in science and technology. (It does not occur to them that their own activities help to make this self-fulfilling.) Hence they often refer to their studios as ‘laboratories’ and their activities as ‘experiments’, using the words in the true scientific sense and not as mere metaphors. They call their jottings about possible future work ‘research notebooks’. Several of them claim to be very interested in sciences such as geology, biology and astrophysics, as if charcoaling a big black circle on a map of the stars to represent a black hole was evidence of serious interest rather than of intellectual frivolity. Whenever one of these artists uses an expression such as ‘I am interested in…’ or ‘I am fascinated by…’ you know that something shallow or opaque is about to follow. Here is what an artist had to say about his ‘project’, which seemed to consist of cheap wooden trestles and frames with polythene stretched in them, all to the sound of a dreary voice recording:

The issue that haunted me as I conceived the project was how to position the recording instruments as well as objects stemming from the exploitation of an intimate space. The space that attracted me most at the Palais des Beaux-Arts was the second floor balcony. I’d like to set up two modified periscopes through which a few objects installed on the ceiling could be observed. I’d also like to build a small ambulatory space, 1.65 meter high – which is to say my own height – which could be used as a partition, an installation and a space where I could share with visitors.

Reading this, I felt almost sorry for the young artist so dishonestly congratulated by the jury, thereby cruelly giving him the impression that his work and his vapid reflections upon it (haunted, indeed!) were of value, and possibly setting him on a lifetime course of pointless and worthless endeavour. Better that he should be a street-sweeper – a useful and honourable occupation, after all – than waste his existence thus.

The problem, perhaps, is that the idea of being an artist still has romantic cachet, independent of the worth of any art actually produced. The problem with the young artists of the Beaux-Arts is that they are more attached to the idea of art than to art itself. They are not like the six characters of Pirandello is search of an author: they are would-be artists who want to express themselves and who are in search of a subject to express themselves about, as well as a career. Hence their professed interest in astrophysics and the like: the universe is a mere prop to their desire to express themselves and be noticed.

The contrast could not have been greater with an exhibition of Haitian art held at the same time in Paris at the Grand Palais. Haitian artists are not necessarily technically accomplished – though the self-taught sculptors of Port-au-Prince are infinitely more so than the sculptors taught at the Beaux-Arts – but it is obvious at a glance that their artistic expression comes from an inner compulsion to try to make sense of their world and their experiences, and is therefore often very moving as well as aesthetically pleasing.

Neither the director of the school, Nicolas Bourriaud, nor the chairman of the jury, Enrico Lunghi, wrote in their introductions to the catalogue as if the school were an educational establishment where such things as skill and technique should be taught. This, it seems, would be beneath the dignity both of the teachers and students. Instead, as Bourriaud puts it:

… if we are strengthening our ties with art centers, museums, foundations and other cultural institutions, it is in order fully to take on the role every school should play within its artistic ecosystem: that of a space for reflection.

It is clear that for Bourriaud, teaching is at the very best secondary, perhaps not even necessary at all: for Man is a born artist, and all he has to do to achieve his innate artistry is to ‘reflect’ on what is already within him.

It will come as no surprise, I should imagine, to readers to learn that the catalogue was published with a subvention of the French Ministry of Culture and Communication, without which it would certainly not have been published at all. As Enrico Lunghi, director of Luxembourg’s museum of modern art and chairman of the jury, puts it:

We could speak of an institution [the Beaux-Arts] among others, where, without seeming to, the foundations of dominant powers are reproduced and consolidated, inasmuch as the sociology of students prefigures the art world, which is not particularly open to social diversity.

Or to artistic diversity, for that matter.

Anthony Daniels

The Jackdaw, March-April 2015