Things have gone rather quiet on the mortality front since queues stretched around the White Cube block in Mason’s Yard for a sight of Damien Hirst’s £50m sculpture For the Love of God. In those days of skulls and diamonds, Paul Wilks wrote a letter to The Jackdaw lamenting the morbidity of contemporary art, wondering why two horrific world wars had produced “art infused with LIFE” while a record period of peace and prosperity had left a legacy of art obsessed with death.

Things have gone rather quiet on the mortality front since queues stretched around the White Cube block in Mason’s Yard for a sight of Damien Hirst’s £50m sculpture For the Love of God. In those days of skulls and diamonds, Paul Wilks wrote a letter to The Jackdaw lamenting the morbidity of contemporary art, wondering why two horrific world wars had produced “art infused with LIFE” while a record period of peace and prosperity had left a legacy of art obsessed with death.

He had a point – there was a lot of it about. From Ron Mueck’s Dead Dad and the Chapmans’ Hell to Sam Taylor Wood’s time-lapse films of decomposing fruit and furry animals and Marc Quinn’s endless stream of Blood Head selfies, the art world mood music of the turn of the century was the bells of hell going tingalingaling and the tills chachinging. In those halcyon years of boom before the bust, vanitas, vanitas, all was vanitas. Since then, however, things seem to have moved on. Sam Taylor Wood has graduated from death to sex and Marc Quinn, for his new exhibition at White Cube Bermondsey (until 13 September), has turned his attention from reflections on his own mortality to wider considerations of time and tide in big lumpy sculptures of Frozen Waves à la Maggi Hambling.

While it’s still too early to speak of a full recovery, the morbidity does seem to be receding. We’ve heard less from the media about that ghoulish reincarnation of Joseph Beuys, Gunther von Hagens, still trotting his plastinated corpses around the globe, and there’s been mercifully little mention of his Russian fellow-ghoul Andrei Molodkin and his plans to boil down human volunteers into oil. Either the volunteers got cold-pressed feet or Molodkin dropped off the media radar. Either way, it seems to confirm the surmise that economic hardship promotes positive art. Good news for Greece, where we can now look forward to a revival of the Age of Pheidias.

Meanwhile back in Blighty Charles Saatchi – the former financier of the YBA death merchants who made possible The Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living – has been bucking the trend with a silly season exhibition Dead: A Celebration of Mortality at the Saatchi Gallery, timed to publicise the launch of his book of the same title. Bound like a mini-tombstone between fake marble covers with incised gold lettering, this tasteful little tome relays a selection of the Evening Standard newspaper columns in which Saatchi has been jotting his weekly musings on life and death in that strangely disjointed style that makes you think of a clerk in a green visor tapping away at a vintage telegraph machine. Either that or it makes you wonder whether there might not be some connections missing in his brain.

All the same, he does have a tinder-dry sense of humour (though if he’s advertising for the next Mrs S, ‘DSOH’ may not be enough to swing it) and his chapter headings are chuckle-worthy. Some are laugh-out-loud funny in a Seth MacFarlane cartoonish sort of way – ‘Run Over by Your Own Car, Driven by Your Own Dog’. Some are on the Goyaesque side of macabre – ‘The Answer to Population Expansion and Food Shortages: Eat Children.’ Some are sensibly practical – ‘If You Want to Murder Your Spouse, Use Arsenic’ (don’t throttle her in public). Some are Jesuitical – ‘Get to Heaven an Hour before the Devil Knows You’re Dead’ – and some disarmingly self-mocking – ‘Are You Being Bored to Death by this Book?’

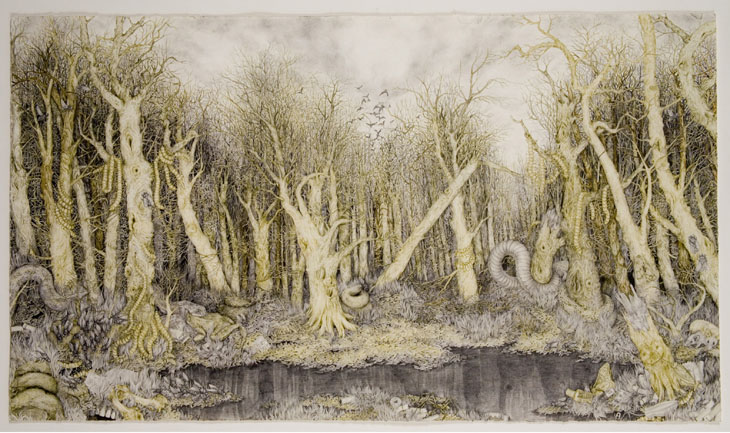

This is what Saatchi is good at: the attention-grabbing one-liner that sells the product. Like his ES pieces, his exhibition was a string of loosely associated thin ideas. He collects art works like he collects facts, in bulk, and presents them in a similarly disconnected way, without argument. One gallery contained photographs of Russian mafia graves, a bomb in a suitcase and a floral tribute made of scrunched-up copies of the Daily Mail stained with blood and tea. Another displayed a pillar formed of resin casts of dead mice, a fake stuffed skunk in a museum case and a pair of genuine animal skins of a cat and dog. A third was a morgue of grotesque human dummies made of urethane wax, old sweaters and bandages, littered around in a range of abject poses. The only exhibit anyone lingered over was Body Swallows World (2006), a truly terrifying drawing of a forest of creepy crawlies by Aurel Schmidt that made Richard Dadd look like Grandma Moses and the Chapmans look ham-fisted. Otherwise, far from striking mortal terror into visitors (most of whom were too young to have begun to think of death) the tone of the exhibition was as insouciant as the small boy leapfrogging a tombstone in the vintage photograph outside the entrance.

My father used to tell a story of a 19th century actor whose onstage deaths were so convincing that the audience would clamour: “Die again, Sam!” and he would oblige. The trouble with Dead: A Celebration of Mortality is that the clamour for its brand of snuff stuff has died down. Almost all the work in the show was pre-financial crash and to post-recessionary eyes it looked like death warmed up. Today’s audiences may not have lived through two world wars, but the past seven years have been no party and they want art which, if not life-affirming, has a bit of depth. Young artists have stopped making schlock art about death and older ones with any sense have grown out of it. The former YBA Mat Collishaw – who came to fame with the gory Bullet Hole shown at Freeze and now in the collection of the Saatchi of the Southern Hemisphere, David Walsh – has progressed to subtler meditations on mortality in his 2013 series of photographic still lifes, Last Meal on Death Row.

One essay in Saatchi’s book tells the cautionary tale of American news anchor Christine Chubbuck who shot herself on screen in 1974 in protest at her channel’s obsession with gore. There’s only so much death a body can take. Even Damien Hirst, whose obsession with mortality may well be genuine, has stopped trying to flog a dead horse – with or without golden hooves – and started looking on the bright side of the life cycle. It began with that hideous series of Fact Paintings (2005-6) painted from photographs of the caesarian birth of his third son Cyrus and has continued in The Miraculous Journey, the recent sequence of equally hideous bronzes of developing foetuses commissioned as street furniture by the Qatari Royal Family in the run-up (they hope) to the 2022 Doha World Cup. Ironically, this is one case where funerary monuments to dead Nepalese workers might be more appropriate.

Washed-up celebrity artistes end up in Vegas; washed-up celebrity artists end up in Doha. It’s no coincidence that both are deserts. On home turf, meanwhile, Hirst is following in the footsteps of his old patron Saatchi and seeking a new form of artistic immortality as a philanthropic museum owner. His free gallery in Newport Street, Lambeth, opening in October, is being built to house his morbidly titled Murderme Collection, but its inaugural show will be a life-affirming exhibition of paintings by his old adversary John Hoyland. Cheer, up everyone! There may be life after death.

Laura Gascoigne

Overkill: art rising from the dead

He had a point – there was a lot of it about. From Ron Mueck’s Dead Dad and the Chapmans’ Hell to Sam Taylor Wood’s time-lapse films of decomposing fruit and furry animals and Marc Quinn’s endless stream of Blood Head selfies, the art world mood music of the turn of the century was the bells of hell going tingalingaling and the tills chachinging. In those halcyon years of boom before the bust, vanitas, vanitas, all was vanitas. Since then, however, things seem to have moved on. Sam Taylor Wood has graduated from death to sex and Marc Quinn, for his new exhibition at White Cube Bermondsey (until 13 September), has turned his attention from reflections on his own mortality to wider considerations of time and tide in big lumpy sculptures of Frozen Waves à la Maggi Hambling.

While it’s still too early to speak of a full recovery, the morbidity does seem to be receding. We’ve heard less from the media about that ghoulish reincarnation of Joseph Beuys, Gunther von Hagens, still trotting his plastinated corpses around the globe, and there’s been mercifully little mention of his Russian fellow-ghoul Andrei Molodkin and his plans to boil down human volunteers into oil. Either the volunteers got cold-pressed feet or Molodkin dropped off the media radar. Either way, it seems to confirm the surmise that economic hardship promotes positive art. Good news for Greece, where we can now look forward to a revival of the Age of Pheidias.

Meanwhile back in Blighty Charles Saatchi – the former financier of the YBA death merchants who made possible The Impossibility of Death in the Mind of Someone Living – has been bucking the trend with a silly season exhibition Dead: A Celebration of Mortality at the Saatchi Gallery, timed to publicise the launch of his book of the same title. Bound like a mini-tombstone between fake marble covers with incised gold lettering, this tasteful little tome relays a selection of the Evening Standard newspaper columns in which Saatchi has been jotting his weekly musings on life and death in that strangely disjointed style that makes you think of a clerk in a green visor tapping away at a vintage telegraph machine. Either that or it makes you wonder whether there might not be some connections missing in his brain.

All the same, he does have a tinder-dry sense of humour (though if he’s advertising for the next Mrs S, ‘DSOH’ may not be enough to swing it) and his chapter headings are chuckle-worthy. Some are laugh-out-loud funny in a Seth MacFarlane cartoonish sort of way – ‘Run Over by Your Own Car, Driven by Your Own Dog’. Some are on the Goyaesque side of macabre – ‘The Answer to Population Expansion and Food Shortages: Eat Children.’ Some are sensibly practical – ‘If You Want to Murder Your Spouse, Use Arsenic’ (don’t throttle her in public). Some are Jesuitical – ‘Get to Heaven an Hour before the Devil Knows You’re Dead’ – and some disarmingly self-mocking – ‘Are You Being Bored to Death by this Book?’

This is what Saatchi is good at: the attention-grabbing one-liner that sells the product. Like his ES pieces, his exhibition was a string of loosely associated thin ideas. He collects art works like he collects facts, in bulk, and presents them in a similarly disconnected way, without argument. One gallery contained photographs of Russian mafia graves, a bomb in a suitcase and a floral tribute made of scrunched-up copies of the Daily Mail stained with blood and tea. Another displayed a pillar formed of resin casts of dead mice, a fake stuffed skunk in a museum case and a pair of genuine animal skins of a cat and dog. A third was a morgue of grotesque human dummies made of urethane wax, old sweaters and bandages, littered around in a range of abject poses. The only exhibit anyone lingered over was Body Swallows World (2006), a truly terrifying drawing of a forest of creepy crawlies by Aurel Schmidt that made Richard Dadd look like Grandma Moses and the Chapmans look ham-fisted. Otherwise, far from striking mortal terror into visitors (most of whom were too young to have begun to think of death) the tone of the exhibition was as insouciant as the small boy leapfrogging a tombstone in the vintage photograph outside the entrance.

My father used to tell a story of a 19th century actor whose onstage deaths were so convincing that the audience would clamour: “Die again, Sam!” and he would oblige. The trouble with Dead: A Celebration of Mortality is that the clamour for its brand of snuff stuff has died down. Almost all the work in the show was pre-financial crash and to post-recessionary eyes it looked like death warmed up. Today’s audiences may not have lived through two world wars, but the past seven years have been no party and they want art which, if not life-affirming, has a bit of depth. Young artists have stopped making schlock art about death and older ones with any sense have grown out of it. The former YBA Mat Collishaw – who came to fame with the gory Bullet Hole shown at Freeze and now in the collection of the Saatchi of the Southern Hemisphere, David Walsh – has progressed to subtler meditations on mortality in his 2013 series of photographic still lifes, Last Meal on Death Row.

One essay in Saatchi’s book tells the cautionary tale of American news anchor Christine Chubbuck who shot herself on screen in 1974 in protest at her channel’s obsession with gore. There’s only so much death a body can take. Even Damien Hirst, whose obsession with mortality may well be genuine, has stopped trying to flog a dead horse – with or without golden hooves – and started looking on the bright side of the life cycle. It began with that hideous series of Fact Paintings (2005-6) painted from photographs of the caesarian birth of his third son Cyrus and has continued in The Miraculous Journey, the recent sequence of equally hideous bronzes of developing foetuses commissioned as street furniture by the Qatari Royal Family in the run-up (they hope) to the 2022 Doha World Cup. Ironically, this is one case where funerary monuments to dead Nepalese workers might be more appropriate.

Washed-up celebrity artistes end up in Vegas; washed-up celebrity artists end up in Doha. It’s no coincidence that both are deserts. On home turf, meanwhile, Hirst is following in the footsteps of his old patron Saatchi and seeking a new form of artistic immortality as a philanthropic museum owner. His free gallery in Newport Street, Lambeth, opening in October, is being built to house his morbidly titled Murderme Collection, but its inaugural show will be a life-affirming exhibition of paintings by his old adversary John Hoyland. Cheer, up everyone! There may be life after death.

Laura Gascoigne

Share: