Laura Gascoigne

March/April 2018

In the Royal Academy’s Tennant Gallery a man in goggles is lurching around waving his arms like someone conducting an orchestra on ketamine. It could be a piece of performance art, but it’s too amusing. In fact the man isn’t air-conducting, he’s air-drawing and the results are appearing in real time on a screen.

Time is the only thing about this operation that’s real because it’s an experiment in virtual reality, one of three “exploring emerging technologies” connected with the RA’s exhibition From Life. The technology comes courtesy of HTC Vive, the exhibition’s Virtual Reality Partner, and coincides with the launch of VIVE Arts, a multimillion-dollar VR program “set to change the way the world creates and engages with the arts”.

The air-drawing exercise is the contribution of Humphrey Ocean RA, its object being to create a 3-D figure to occupy a chair in virtual space. The figure on this occasion looks like Jabba the Hutt made of dayglow Play-Doh, and not wanting to blunder about like a blindfolded idiot and draw something worse I choose the Yinka Shonibare option of entering a neoclassical painting by Gavin Hamilton, with added Townley Venus draped in batik. A warning to VR goggle-wearers: do not adjust your set. I twiddled a knob at the side of mine, imagining they were binoculars, and it looked as if Gerhard Richter had taken a squeegee to Hamilton’s view until the attendant fixed it. Even then the visual experience felt no more real than a 3-D view of the Acropolis seen through a 1950s stereoscopic slide viewer. But contemporary armchair travellers wishing to enjoy it in the comfort of their homes may be pleased to hear that it’s available on Viveport HTC’s global VR app store. Like most things digital, Virtual Reality poses as ‘shared experience’ but is essentially sol-app-sistic.

Along with Google Arts & Culture, another partner of the RA show, HTC VIVE has been busily “investing in the arts and culture space”. The same company is behind The Ochre Atelier in Tate Modern’s Modigliani exhibition, a virtual recreation of the artist’s last Paris studio with the declared aim of “bringing visitors closer to the artist’s world”. Unlike the VR experiences in From Life, for which on a weekday afternoon I was the only taker (the man in goggles being an off-duty attendant), on a Saturday evening The Ochre Atelier attracted a half-hour queue. Fortunately I had taken a copy of The Jackdaw for company.

It was a relief to find that as a “seated experience” this doesn’t involve floundering about like a fool in public, and the visual quality is also far more ‘real’. You sit in a chair between the stove and the easel while a cigarette burns endlessly in an ashtray and street noises drift in through an open window. When you fix an object in your sights the voice of a Tate curator divulges a related snippet of information, such as the extraordinary fact that drink was a comfort to Modigliani, “not a vice” – something that will be a comfort to piss artists everywhere. What fascinated me was the half-open frosted window through which, by craning your neck to the left or right, you can catch glimpses of the buildings opposite. I was seriously tempted to get up and look out of it. But as far as getting an insight into an artist’s mindset – as opposed to headset – you’d learn more from a visit to a living artist’s studio. You might even get a drink.

Studies reveal that gallery-goers spend less than 30 seconds in front of a picture, yet they are prepared to queue for 30 minutes for a 6-minute VR experience. Why? Because looking no longer counts as an experience. VR is just another step in the creeping annexation of the concept of ‘experience’ by technology, until people no longer trust their senses to work unaided without some sort of digital prosthesis. The VR people smell money in art and they’re getting in there. Last year in Knokke the VR company BDH marked the 50th anniversary of Magritte’s death with a cinema installation in a bowler hat – “an illusion René would adore”, cooed the critic of Le Soir – and for the Bosch500Fest in ’s-Hertogenbosch they installed a virtual Garden of Earthly Delights in the artist’s studio. “We are impressed by the authenticity of the experience,” declares the festival’s director Lian Duif on the company’s website. The reaction of the man on the street in Austin, Texas enjoying the experience via Google Cardboard Viewer is more effusive. “This painting is 500 years old? The whole thing? That’s wild, that’s dope, it’s 500 years old!”

Dali will be next, as sure as clocks is cheese. In the meantime, contemporary artists are getting on board. A new VR platform, Acute Art, which launched in January with a mission to “encourage art’s transition from the physical art world to the new age”, has signed up Olafur Eliasson, Jeff Koons and Marina Abramovic. Eliasson has created a VR rainbow, Koons is working on resuscitating the Greek courtesan Phryne – as a shiny Phryne, “to bring the affirmation of self into VR” – and Abramovic, concerned about “the climate crisis shaking the IRL world” (that’s the ‘In Real Life’ world to you and me) is developing an interactive work giving audiences the option of saving her avatar from rising waters in a tank or leaving her to drown. Which would you choose?

Not to be left behind, during Nobel Week in Gothenburg last December Anish Kapoor gave assembled Laureates a preview of his debut VR work, Into Yourself-Fall, and took part in a discussion with Daniel Birnbaum on the theme of ‘Artistic Truth in Virtual Space’. Birnbaum popped up again in January as curator of the Verbier Art Summit, ‘More than Real: Art in the Digital Age’, at which keynote speakers included Eliasson and Acute Art’s founder Dado Valentic. “Technology will change art in the most fundamental way,” Birnbaum predicted, paraphrasing Walter Benjamin in his statement that “it is art’s task to create a demand which can only be fully satisfied later”. And there was me thinking that was the task of business.

It is possible to do good things with VR. I’m prepared to believe that Alejandro Iñárritu’s 6-minute VR essay Carne y Arena recreating the experience of Mexican migrants crossing the Sonoran desert into America deserved the special Oscar it was awarded last November. Film directors tend to make better films than artists. And VR is a useful tool for reimagining ancient sites like the Baths of Caracalla, or restaging historic events like Mat Collishaw’s recreation at Somerset House last summer of Fox Talbot’s first photographic exhibition. It’s not so great, yet, at “fully immersive, experiential sexual technology” as attempted by Ed Fornieles in Truth Table: Be Everyone, Fuck Everyone at Carlos/Ishikawa last September, though the porn sites are working on it. But however good the quality gets, VR will never bring us closer to an artist than standing a foot away from the surface of a canvas painted 500 years ago. That’s wild, that’s dope. No invention of technology will ever be more miraculous than the naked eye, an instrument whose pleasures most of us have not begun to exhaust. Let’s not forget how to use it.

Laura Gascoigne: Visual Experience with Knobs On – March 2018

Laura Gascoigne

March/April 2018

In the Royal Academy’s Tennant Gallery a man in goggles is lurching around waving his arms like someone conducting an orchestra on ketamine. It could be a piece of performance art, but it’s too amusing. In fact the man isn’t air-conducting, he’s air-drawing and the results are appearing in real time on a screen.

Time is the only thing about this operation that’s real because it’s an experiment in virtual reality, one of three “exploring emerging technologies” connected with the RA’s exhibition From Life. The technology comes courtesy of HTC Vive, the exhibition’s Virtual Reality Partner, and coincides with the launch of VIVE Arts, a multimillion-dollar VR program “set to change the way the world creates and engages with the arts”.

The air-drawing exercise is the contribution of Humphrey Ocean RA, its object being to create a 3-D figure to occupy a chair in virtual space. The figure on this occasion looks like Jabba the Hutt made of dayglow Play-Doh, and not wanting to blunder about like a blindfolded idiot and draw something worse I choose the Yinka Shonibare option of entering a neoclassical painting by Gavin Hamilton, with added Townley Venus draped in batik. A warning to VR goggle-wearers: do not adjust your set. I twiddled a knob at the side of mine, imagining they were binoculars, and it looked as if Gerhard Richter had taken a squeegee to Hamilton’s view until the attendant fixed it. Even then the visual experience felt no more real than a 3-D view of the Acropolis seen through a 1950s stereoscopic slide viewer. But contemporary armchair travellers wishing to enjoy it in the comfort of their homes may be pleased to hear that it’s available on Viveport HTC’s global VR app store. Like most things digital, Virtual Reality poses as ‘shared experience’ but is essentially sol-app-sistic.

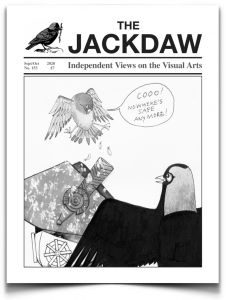

Along with Google Arts & Culture, another partner of the RA show, HTC VIVE has been busily “investing in the arts and culture space”. The same company is behind The Ochre Atelier in Tate Modern’s Modigliani exhibition, a virtual recreation of the artist’s last Paris studio with the declared aim of “bringing visitors closer to the artist’s world”. Unlike the VR experiences in From Life, for which on a weekday afternoon I was the only taker (the man in goggles being an off-duty attendant), on a Saturday evening The Ochre Atelier attracted a half-hour queue. Fortunately I had taken a copy of The Jackdaw for company.

It was a relief to find that as a “seated experience” this doesn’t involve floundering about like a fool in public, and the visual quality is also far more ‘real’. You sit in a chair between the stove and the easel while a cigarette burns endlessly in an ashtray and street noises drift in through an open window. When you fix an object in your sights the voice of a Tate curator divulges a related snippet of information, such as the extraordinary fact that drink was a comfort to Modigliani, “not a vice” – something that will be a comfort to piss artists everywhere. What fascinated me was the half-open frosted window through which, by craning your neck to the left or right, you can catch glimpses of the buildings opposite. I was seriously tempted to get up and look out of it. But as far as getting an insight into an artist’s mindset – as opposed to headset – you’d learn more from a visit to a living artist’s studio. You might even get a drink.

Studies reveal that gallery-goers spend less than 30 seconds in front of a picture, yet they are prepared to queue for 30 minutes for a 6-minute VR experience. Why? Because looking no longer counts as an experience. VR is just another step in the creeping annexation of the concept of ‘experience’ by technology, until people no longer trust their senses to work unaided without some sort of digital prosthesis. The VR people smell money in art and they’re getting in there. Last year in Knokke the VR company BDH marked the 50th anniversary of Magritte’s death with a cinema installation in a bowler hat – “an illusion René would adore”, cooed the critic of Le Soir – and for the Bosch500Fest in ’s-Hertogenbosch they installed a virtual Garden of Earthly Delights in the artist’s studio. “We are impressed by the authenticity of the experience,” declares the festival’s director Lian Duif on the company’s website. The reaction of the man on the street in Austin, Texas enjoying the experience via Google Cardboard Viewer is more effusive. “This painting is 500 years old? The whole thing? That’s wild, that’s dope, it’s 500 years old!”

Dali will be next, as sure as clocks is cheese. In the meantime, contemporary artists are getting on board. A new VR platform, Acute Art, which launched in January with a mission to “encourage art’s transition from the physical art world to the new age”, has signed up Olafur Eliasson, Jeff Koons and Marina Abramovic. Eliasson has created a VR rainbow, Koons is working on resuscitating the Greek courtesan Phryne – as a shiny Phryne, “to bring the affirmation of self into VR” – and Abramovic, concerned about “the climate crisis shaking the IRL world” (that’s the ‘In Real Life’ world to you and me) is developing an interactive work giving audiences the option of saving her avatar from rising waters in a tank or leaving her to drown. Which would you choose?

Not to be left behind, during Nobel Week in Gothenburg last December Anish Kapoor gave assembled Laureates a preview of his debut VR work, Into Yourself-Fall, and took part in a discussion with Daniel Birnbaum on the theme of ‘Artistic Truth in Virtual Space’. Birnbaum popped up again in January as curator of the Verbier Art Summit, ‘More than Real: Art in the Digital Age’, at which keynote speakers included Eliasson and Acute Art’s founder Dado Valentic. “Technology will change art in the most fundamental way,” Birnbaum predicted, paraphrasing Walter Benjamin in his statement that “it is art’s task to create a demand which can only be fully satisfied later”. And there was me thinking that was the task of business.

It is possible to do good things with VR. I’m prepared to believe that Alejandro Iñárritu’s 6-minute VR essay Carne y Arena recreating the experience of Mexican migrants crossing the Sonoran desert into America deserved the special Oscar it was awarded last November. Film directors tend to make better films than artists. And VR is a useful tool for reimagining ancient sites like the Baths of Caracalla, or restaging historic events like Mat Collishaw’s recreation at Somerset House last summer of Fox Talbot’s first photographic exhibition. It’s not so great, yet, at “fully immersive, experiential sexual technology” as attempted by Ed Fornieles in Truth Table: Be Everyone, Fuck Everyone at Carlos/Ishikawa last September, though the porn sites are working on it. But however good the quality gets, VR will never bring us closer to an artist than standing a foot away from the surface of a canvas painted 500 years ago. That’s wild, that’s dope. No invention of technology will ever be more miraculous than the naked eye, an instrument whose pleasures most of us have not begun to exhaust. Let’s not forget how to use it.

Share: