The house-museums of two Belgian masters of the 19th Century shed light on artistic and social concerns of the era. As case studies they exemplify dominant thematic trends in both halves of that century – Romanticism in the first half and Realism in the second.

The house-museums of two Belgian masters of the 19th Century shed light on artistic and social concerns of the era. As case studies they exemplify dominant thematic trends in both halves of that century – Romanticism in the first half and Realism in the second.

Antoine Wiertz (1806-1865) was born to an impoverished family in Dinant, Wallonia (later Belgium). After studying at Antwerp Art Academy, he won the (Belgian) Prix de Rome at a second try, in 1832. His grand manner was Romantic and painterly, derived from Rubens. His subjects anticipate those of the Symbolists. Though Wiertz made his name with historical and religious compositions, the allegories and (often gruesome) scenes of contemporary life are his most distinctive contributions to art.

In 1850, partly in order to establish Belgian art as independent of French influence (led by the School of David; J-L David (1714-1825) spent his last years in Brussels) the newly formed state agreed to build a studio and dwelling for the benefit of Wiertz, the first truly “Belgian” artist. The initial agreement was that the artist would donate works to the state but it seems Wiertz early on had the idea of turning the studio into a permanent museum. The government drew the line at Wiertz’s proposal to fund the construction of a ruined temple in the studio grounds. Upon the artist’s death the combined house and studio became possessions of the state. Both building and grounds have remained unchanged since 1868, now a fragment of a lost age lodged under the glass towers of the European Parliament.

Photographs leave one unprepared for the vast scale of the studio and its contents. The studio is 35m long, 15m wide and 16m high, accommodating gargantuan canvases almost as tall and wide as the walls. Subjects are suitably grand: the fall of the rebel angels, Christ triumphant, Homeric scenes. The paintings offer a serious challenge to conservators. Aside from the technical experimentation discussed later, their size presents difficulties. Expanses of canvas bulge down from tilted frames, unsupported from behind. Extensive restoration of Musée Wiertz (completed in 2009) involved reconstruction of the roof and repair of the walls, which have been returned to their original grey colour.

Wiertz: La Belle Rosine (Two Young Girls)

If you can find anything written about Wiertz, it is almost all negative. Novotny gives Wiertz three sentences in his Painting and Sculpture in Europe 1780-1880, the last being “His wild-eyed hysteria is a mere caricature of real passion.” The disdain and distaste for Wiertz is evident from the start of his career. The first version of Greeks and Trojans Fighting over the Body of Patrocles (first version 1836, Liège, second version 1844, Musée Wiertz) was skied at the Paris Salon of 1839 and mocked by critics. Wiertz became a national cause, though one wonders what misgivings Belgians must have had about their standard bearer. In terms of grandiose aspirations, hyperbolic acclaim and posthumous neglect, the story of Wiertz’s art is comparable to that of GF Watts’s.

The only good word anyone seems to have is for La Belle Rosine (1847), Wiertz’s most famous invention. This painting, influential and much reproduced, is excepted as “a good chord on a bad piano”. It shows a nude woman contemplating a skeleton. The alternative title is Two Young Women. Now very fragile, the painting is unlikely to leave Brussels again. Death and the Maiden is an oft-reprised subject but there can’t have been a more compelling version than this. The woman, garland in her hair, gazes with hypnotic calmness into the vacant eye sockets of the anatomist’s specimen. Below the suspended partial skeleton (missing its leg bones) are fragments of an ancient statue. A label on the skull carries the inscription “La Belle Rosine”. One might interpret this two ways. The painter is using a graphic intervention to insert the title of the picture or – more likely – the label identifies the skeleton as that of Rosine. (The issue of titling is a curious one. Wiertz did give certain pictures exact titles. It seems fixed, artist-given titles only began in earnest with the advent of the Paris salons in the early 18th Century. Before then works were discussed by topic. Vasari refers to “a Madonna by the hand of…”; “a Dead Christ in the lap of Our Lady, surrounded by many figures”; “a panel made for the Duke of Urbino”; and so forth. The idea that paintings should have a definite title is essentially a modern construction, in that it derives from the practice of organised temporary public exhibitions. Some scenes of a narrative or anecdotal character can depend to a degree on a title. Think of When did you last see your Father? by WF Yeames in the Walker Art Gallery.)

Little work is at the level of La Belle Rosine, though there are other paintings worth attention. La Liseuse de Romans (The Novel Reader) (1853) has a recumbent female nude reading on a bed, unaware of the figure reaching towards a book beside her. The Devil’s Mirror (1856) adapts Goya’s Maja paintings, with one canvas showing a clothed woman at a mirror and the pendant with the woman unclothed, the Devil hidden behind her mirror. A modest trompe l’oeil still-life painted when Wiertz was a student is skilfully designed and realised. There is a sensitive painting of the artist’s dog asleep on a chair.

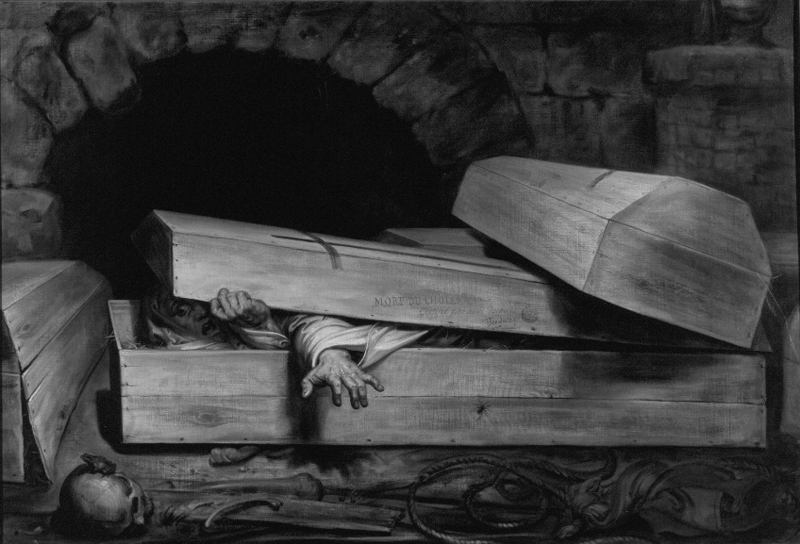

Wiertz was a committed humanitarian and campaigner for social reform. The Burnt Child was originally entitled If there were Crêches and was inspired by a newspaper report of an unmarried mother who left her child by a fire to keep warm while she worked. When she returned she discovered the child burned. The Premature Burial (1854) shows a terrified man forcing open his own coffin marked “MORT DU CHOLERA”. It is both a sensational scene of horror and social criticism of the not-infrequent phenomenon of premature interment of cholera victims. Doctors could be lax about distinguishing between death and coma. Some victims were regarded as hopeless cases and deliberately consigned to the tomb while still alive.

Wiertz was a committed humanitarian and campaigner for social reform. The Burnt Child was originally entitled If there were Crêches and was inspired by a newspaper report of an unmarried mother who left her child by a fire to keep warm while she worked. When she returned she discovered the child burned. The Premature Burial (1854) shows a terrified man forcing open his own coffin marked “MORT DU CHOLERA”. It is both a sensational scene of horror and social criticism of the not-infrequent phenomenon of premature interment of cholera victims. Doctors could be lax about distinguishing between death and coma. Some victims were regarded as hopeless cases and deliberately consigned to the tomb while still alive.

The evidence of carved versions of Wiertz’s models suggests he was an able sculptor. His Triumph of Light (1860-2) is said to have inspired Bartholdi’s Statue of Liberty (1876/1886), though the resemblance seems coincidental.

To describe Wiertz as inconsistent is an understatement. His triptych of Christ in the Tomb (1839), with wing panels of female nudes, is badly misjudged. The Suicide (1854) shows a man shooting himself in the head with a pistol. A praying attendant angel has closed her eyes, as well she might. There are many other pictures that prompt a viewer to wonder “What could he have been thinking?” There can hardly have been another artist who has failed and succeeded to such extreme degrees.

The depiction of a guillotining may have been well meant (the artist apparently attended a public execution and was appalled) but the result is incoherent and ineffective. Additionally, it is painted in Wiertz’s essence technique and has deteriorated appreciably. Noting the troublesome reflection from conventional varnished oil paintings, Wiertz devised a technique to combat sheen. He used essence, which is oil paint with the binder largely extracted (usually done by allowing the oil medium to soak into an absorbent substance, such as blotting paper), mixing it with turpentine or a mineral thinner and applying it directly to unprimed flax. This technique effectively removed gloss but over the years it has proved prone to fading. Worse still, the low proportion of binder to pigment has left the paint powdery. These fragile paintings are not possible to frame or clean, prohibitively expensive to restore and now impossible to move.

Alongside criticisms of morbidity, hubris and sensationalism (all reasonable reproaches) is another charge, that of titillation. (A current guidebook mentions “saucy girls in a state of undress”.) This is more debatable. If one looks at the figures in question, there is less nudity than one finds in Rubens, the female anatomies are not entirely convincing and there is nothing overtly sexual in the poses, even for the period. It comes as no surprise to discover Wiertz was homosexual (or at least bisexual); an idea first publicly aired by the critic Camille Lemonnier, who lived very close to the artist.

Drawings and small painted sketches are strongly reminiscent of Blake’s in their muscular Mannerism, though Wiertz understood anatomy better. The two artists share many characteristics (ambition, stubbornness, independence, keen social conscience and admiration for Michelangelo), though at his best Wiertz is more than Blake’s equal in inventiveness, power and skill. On consideration, the received views of “Blake the Visionary” and “Wiertz the Deluded” turn out to be not only disputable but reversible. Didn’t Wiertz put his sense of justice into his art rather than into theological disquisitions at 12 shillings apiece?

Wiertz’s aspirations may have been grandiose but his own circumstances were straitened. He painted allegories for political and artistic reasons and kept them in his studio for the nation. To eke out a living he painted portraits. The decorative edges of some canvases came about because he could not afford frames. Upon his death his possessions were found to be few, his furniture to be borrowed and his clothes to be much mended.

The museum’s over 200 works constitute the majority of Wiertz’s (identified) output and the delicate condition of the most important pieces entail that a meaningful retrospective outside of the museum will never be possible. This fact and the unique ambience make a visit to Musée Wiertz a fascinating experience. It is hard to look at the anonymous pastel of Wiertz on his deathbed without feeling a touch of sympathy and admiration for this proud, difficult man.

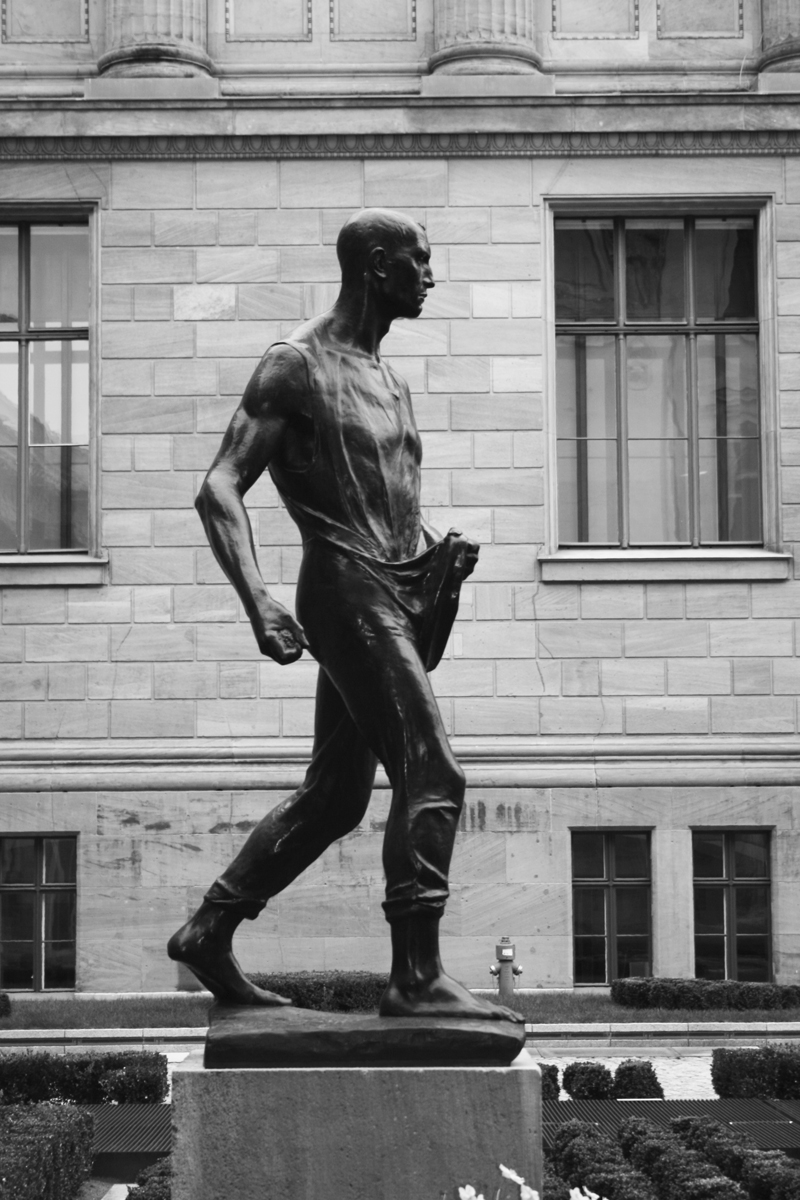

Meunier Reaccessioned. A statue formerly in the collection of the Berlin Museums has been reacquired. The Sower (1896), (above) by Constantin Meunier was appropriated from a private collection by the GDR. The work, one among a number of bronzes by Rodin, Degas and Maillol, was returned to the ownership of the family of the original owner. At an auction of the works this year The Sower was purchased on behalf of the Alte Nationalgalerie. It is now sited in the colonnaded courtyard between the Alte Nationalgalerie and the newly opened Neues Museum

Meunier is an artist of a different stamp. The only things Meunier and Wiertz shared were a nationality, profession and an interest in social reform. Constantin Meunier (1831-1905) took the plight of workers in Belgium’s farms and heavy industries as his principal subject relatively late in his career (around 1875). (The few early History and travel scenes on display in the museum are undistinguished.) His principal medium was sculpture, though he was a skilled draughtsman and a competent painter. His slightly over-life-size bronze figures have the heroism of Rodin tempered by the Realism of Courbet’s Stone Breakers (1849-1850; exhibited at the Brussels Salon of 1851). The coalminers and iron workers of the Borinage are ennobled through working for the common good. The sculptor then further dignifies them by raising them to art. By so doing the artist himself works for the benefit of his subjects and for society more generally.

The house and studio were purpose built for the sculptor over 1899-1900. The main salon is connected via a long corridor to the sculpture studio built in the grounds of the house. The studio accommodates a number of statues and maquettes, with a few larger paintings. Only a fraction of the collection is on show. The property and collection were acquired by the state from Meunier’s heirs in 1936.

The sculptures are all well conceived and executed with a blend of verisimilitude and idealism that became adopted as the template for Socialist Realist public monuments throughout the following century. Few of those sculptors had the talent or sensitivity necessary to attain Meunier’s consistently high standards. Full-bas reliefs, executed in bronze and smaller than life size, convey the volume and presence of figures and the interaction of them with their environment. In the mine one feels the claustrophobic closeness of the rough walls; in the field one sees the toilers against the swaying striations of tall wheat stalks. His pictures are effective but the unremitting earth hues – though honest – are obvious and deadening. (Van Gogh was an admirer of his, making 13 references to Meunier’s art in his letters.) A large triptych on the subject of coal mining has little of the energy and economy of the drawings.

Let us hope these old-fashioned museums remain unchanged while becoming better known. Both are windows on a past well worth looking through.

The author would like to thank Dr Brita Velghe for her assistance in researching this article.

Alexander Adams is an artist and writer based in Berlin.

The Jackdaw, Jan-Feb 2011

The Belgian Blake: Alexander Adams visits two little-known artist-museums in Brussels, the Musées Wiertz and Meunier

Antoine Wiertz (1806-1865) was born to an impoverished family in Dinant, Wallonia (later Belgium). After studying at Antwerp Art Academy, he won the (Belgian) Prix de Rome at a second try, in 1832. His grand manner was Romantic and painterly, derived from Rubens. His subjects anticipate those of the Symbolists. Though Wiertz made his name with historical and religious compositions, the allegories and (often gruesome) scenes of contemporary life are his most distinctive contributions to art.

In 1850, partly in order to establish Belgian art as independent of French influence (led by the School of David; J-L David (1714-1825) spent his last years in Brussels) the newly formed state agreed to build a studio and dwelling for the benefit of Wiertz, the first truly “Belgian” artist. The initial agreement was that the artist would donate works to the state but it seems Wiertz early on had the idea of turning the studio into a permanent museum. The government drew the line at Wiertz’s proposal to fund the construction of a ruined temple in the studio grounds. Upon the artist’s death the combined house and studio became possessions of the state. Both building and grounds have remained unchanged since 1868, now a fragment of a lost age lodged under the glass towers of the European Parliament.

Photographs leave one unprepared for the vast scale of the studio and its contents. The studio is 35m long, 15m wide and 16m high, accommodating gargantuan canvases almost as tall and wide as the walls. Subjects are suitably grand: the fall of the rebel angels, Christ triumphant, Homeric scenes. The paintings offer a serious challenge to conservators. Aside from the technical experimentation discussed later, their size presents difficulties. Expanses of canvas bulge down from tilted frames, unsupported from behind. Extensive restoration of Musée Wiertz (completed in 2009) involved reconstruction of the roof and repair of the walls, which have been returned to their original grey colour.

Wiertz: La Belle Rosine (Two Young Girls)

If you can find anything written about Wiertz, it is almost all negative. Novotny gives Wiertz three sentences in his Painting and Sculpture in Europe 1780-1880, the last being “His wild-eyed hysteria is a mere caricature of real passion.” The disdain and distaste for Wiertz is evident from the start of his career. The first version of Greeks and Trojans Fighting over the Body of Patrocles (first version 1836, Liège, second version 1844, Musée Wiertz) was skied at the Paris Salon of 1839 and mocked by critics. Wiertz became a national cause, though one wonders what misgivings Belgians must have had about their standard bearer. In terms of grandiose aspirations, hyperbolic acclaim and posthumous neglect, the story of Wiertz’s art is comparable to that of GF Watts’s.

The only good word anyone seems to have is for La Belle Rosine (1847), Wiertz’s most famous invention. This painting, influential and much reproduced, is excepted as “a good chord on a bad piano”. It shows a nude woman contemplating a skeleton. The alternative title is Two Young Women. Now very fragile, the painting is unlikely to leave Brussels again. Death and the Maiden is an oft-reprised subject but there can’t have been a more compelling version than this. The woman, garland in her hair, gazes with hypnotic calmness into the vacant eye sockets of the anatomist’s specimen. Below the suspended partial skeleton (missing its leg bones) are fragments of an ancient statue. A label on the skull carries the inscription “La Belle Rosine”. One might interpret this two ways. The painter is using a graphic intervention to insert the title of the picture or – more likely – the label identifies the skeleton as that of Rosine. (The issue of titling is a curious one. Wiertz did give certain pictures exact titles. It seems fixed, artist-given titles only began in earnest with the advent of the Paris salons in the early 18th Century. Before then works were discussed by topic. Vasari refers to “a Madonna by the hand of…”; “a Dead Christ in the lap of Our Lady, surrounded by many figures”; “a panel made for the Duke of Urbino”; and so forth. The idea that paintings should have a definite title is essentially a modern construction, in that it derives from the practice of organised temporary public exhibitions. Some scenes of a narrative or anecdotal character can depend to a degree on a title. Think of When did you last see your Father? by WF Yeames in the Walker Art Gallery.)

Little work is at the level of La Belle Rosine, though there are other paintings worth attention. La Liseuse de Romans (The Novel Reader) (1853) has a recumbent female nude reading on a bed, unaware of the figure reaching towards a book beside her. The Devil’s Mirror (1856) adapts Goya’s Maja paintings, with one canvas showing a clothed woman at a mirror and the pendant with the woman unclothed, the Devil hidden behind her mirror. A modest trompe l’oeil still-life painted when Wiertz was a student is skilfully designed and realised. There is a sensitive painting of the artist’s dog asleep on a chair.

The evidence of carved versions of Wiertz’s models suggests he was an able sculptor. His Triumph of Light (1860-2) is said to have inspired Bartholdi’s Statue of Liberty (1876/1886), though the resemblance seems coincidental.

To describe Wiertz as inconsistent is an understatement. His triptych of Christ in the Tomb (1839), with wing panels of female nudes, is badly misjudged. The Suicide (1854) shows a man shooting himself in the head with a pistol. A praying attendant angel has closed her eyes, as well she might. There are many other pictures that prompt a viewer to wonder “What could he have been thinking?” There can hardly have been another artist who has failed and succeeded to such extreme degrees.

The depiction of a guillotining may have been well meant (the artist apparently attended a public execution and was appalled) but the result is incoherent and ineffective. Additionally, it is painted in Wiertz’s essence technique and has deteriorated appreciably. Noting the troublesome reflection from conventional varnished oil paintings, Wiertz devised a technique to combat sheen. He used essence, which is oil paint with the binder largely extracted (usually done by allowing the oil medium to soak into an absorbent substance, such as blotting paper), mixing it with turpentine or a mineral thinner and applying it directly to unprimed flax. This technique effectively removed gloss but over the years it has proved prone to fading. Worse still, the low proportion of binder to pigment has left the paint powdery. These fragile paintings are not possible to frame or clean, prohibitively expensive to restore and now impossible to move.

Alongside criticisms of morbidity, hubris and sensationalism (all reasonable reproaches) is another charge, that of titillation. (A current guidebook mentions “saucy girls in a state of undress”.) This is more debatable. If one looks at the figures in question, there is less nudity than one finds in Rubens, the female anatomies are not entirely convincing and there is nothing overtly sexual in the poses, even for the period. It comes as no surprise to discover Wiertz was homosexual (or at least bisexual); an idea first publicly aired by the critic Camille Lemonnier, who lived very close to the artist.

Drawings and small painted sketches are strongly reminiscent of Blake’s in their muscular Mannerism, though Wiertz understood anatomy better. The two artists share many characteristics (ambition, stubbornness, independence, keen social conscience and admiration for Michelangelo), though at his best Wiertz is more than Blake’s equal in inventiveness, power and skill. On consideration, the received views of “Blake the Visionary” and “Wiertz the Deluded” turn out to be not only disputable but reversible. Didn’t Wiertz put his sense of justice into his art rather than into theological disquisitions at 12 shillings apiece?

Wiertz’s aspirations may have been grandiose but his own circumstances were straitened. He painted allegories for political and artistic reasons and kept them in his studio for the nation. To eke out a living he painted portraits. The decorative edges of some canvases came about because he could not afford frames. Upon his death his possessions were found to be few, his furniture to be borrowed and his clothes to be much mended.

The museum’s over 200 works constitute the majority of Wiertz’s (identified) output and the delicate condition of the most important pieces entail that a meaningful retrospective outside of the museum will never be possible. This fact and the unique ambience make a visit to Musée Wiertz a fascinating experience. It is hard to look at the anonymous pastel of Wiertz on his deathbed without feeling a touch of sympathy and admiration for this proud, difficult man.

Meunier Reaccessioned. A statue formerly in the collection of the Berlin Museums has been reacquired. The Sower (1896), (above) by Constantin Meunier was appropriated from a private collection by the GDR. The work, one among a number of bronzes by Rodin, Degas and Maillol, was returned to the ownership of the family of the original owner. At an auction of the works this year The Sower was purchased on behalf of the Alte Nationalgalerie. It is now sited in the colonnaded courtyard between the Alte Nationalgalerie and the newly opened Neues Museum

Meunier is an artist of a different stamp. The only things Meunier and Wiertz shared were a nationality, profession and an interest in social reform. Constantin Meunier (1831-1905) took the plight of workers in Belgium’s farms and heavy industries as his principal subject relatively late in his career (around 1875). (The few early History and travel scenes on display in the museum are undistinguished.) His principal medium was sculpture, though he was a skilled draughtsman and a competent painter. His slightly over-life-size bronze figures have the heroism of Rodin tempered by the Realism of Courbet’s Stone Breakers (1849-1850; exhibited at the Brussels Salon of 1851). The coalminers and iron workers of the Borinage are ennobled through working for the common good. The sculptor then further dignifies them by raising them to art. By so doing the artist himself works for the benefit of his subjects and for society more generally.

The house and studio were purpose built for the sculptor over 1899-1900. The main salon is connected via a long corridor to the sculpture studio built in the grounds of the house. The studio accommodates a number of statues and maquettes, with a few larger paintings. Only a fraction of the collection is on show. The property and collection were acquired by the state from Meunier’s heirs in 1936.

The sculptures are all well conceived and executed with a blend of verisimilitude and idealism that became adopted as the template for Socialist Realist public monuments throughout the following century. Few of those sculptors had the talent or sensitivity necessary to attain Meunier’s consistently high standards. Full-bas reliefs, executed in bronze and smaller than life size, convey the volume and presence of figures and the interaction of them with their environment. In the mine one feels the claustrophobic closeness of the rough walls; in the field one sees the toilers against the swaying striations of tall wheat stalks. His pictures are effective but the unremitting earth hues – though honest – are obvious and deadening. (Van Gogh was an admirer of his, making 13 references to Meunier’s art in his letters.) A large triptych on the subject of coal mining has little of the energy and economy of the drawings.

Let us hope these old-fashioned museums remain unchanged while becoming better known. Both are windows on a past well worth looking through.

The author would like to thank Dr Brita Velghe for her assistance in researching this article.

Alexander Adams is an artist and writer based in Berlin.

The Jackdaw, Jan-Feb 2011

Share: