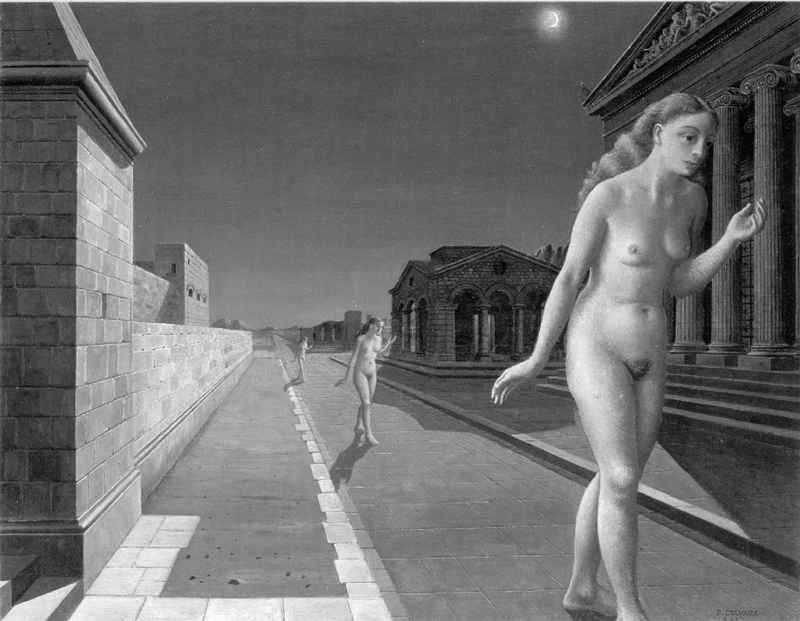

Delvaux: Acropolis, 1966

If you have heard of Belgian painter Paul Delvaux (1897-1994) then it is likely to have been in connection with Surrealism. He gets a couple of illustrations in thematic surveys of Surrealism, rarely more. Unless you locate a specialist publication on the artist, it is hard to get an overview of his development. Delvaux is poorly represented in British public collections.

Born near Liège in 1897, Delvaux initially studied architecture in Brussels, though he abandoned his studies because his grades in mathematics were insufficient, transferring to the painting course. Delvaux’s earliest pieces are landscapes composed with a naturalistic palette, later leavened by Impressionism. As is usual for Belgians of this period, the Impressionism is more a form of vivacious naturalism with vibrant lighting effects and vigorous brushwork rather than sustained application of complimentary colour theory. Throughout the late 1920s he picked up and attempted to blend a welter of (often conflicting) influences: Renoir, Cézanne, Modigliani, Ensor. After 1925 one constant emerges: the human figure, often as a nude, as the principal subject. In the late 1920s Delvaux came into the orbit of Flemish Expressionists (less bold and strident than the Germans, they evolved a dull-hued, restrained style dwelling on figures in domestic settings, clearly displaying an attachment to realism).

Yet even as he was painting the most accomplished works of his career, something was nagging at him. He had seen the art of de Chirico and pondered Wiertz’s La Belle Rosine (see Jackdaw no. 95) and felt there was new territory to be discovered. (In 1922 he painted a view of the entrance to Musée Wiertz.) The example of Magritte proved a decisive spur. By 1935 his figures were becoming more normally proportioned, the palette broader and more conventional and the settings ever more precise and significant. He had arrived at his classic mature style.

What is the typical Delvaux? Although there are distinct phases, we can make some generalisations: the subjects are females, often nude, with dreamlike repose in the surrounding of fantastic architecture, generally a blend of classical, neo-classical and 19th century Belgian. Frequently used settings included train stations, town squares, beaches and temples, often nocturnal and deserted and almost exclusively urban rather than pastoral. The technique is direct, the lighting pellucid, the brushwork unobtrusive.

A typical work is Echo (1943) (currently in a Japanese museum): between ancient buildings at night time a woman walks along a road towards the picture plane; behind her are her echoes – two identical versions of her in the same pose. The ground is arid, indicating we are in Near East or Mediterranean lands. Nothing will ever change, no rain fall, no building deteriorate any further. The world we see is in a state of perfect stasis. Of all paintings (Surrealist or otherwise) these come closest to capturing dreamlike states. There is very little here that is literally impossible – no burning giraffes or floating rocks. The poetry resides in the mood evoked by arranging legible motifs.

Delvaux’s personal collection (as one might have guessed, the largest collection of Delvaux paintings in the world) is housed in a museum in St.-Idesbald, on the coast. To get to Museum Delvaux one takes the tram from Ostend south-west to Koksijde-St.-Idesbald (direction De Panne, zone 7, €2 per journey). During summer the one-hour journey with the dunes on one side and the sea on the other must be picturesque but out of season it is rather bleak. The museum is a low brick building in a residential lane less than ten minutes’ walk from the seafront. It was established in 1982, two years before Delvaux (who lived in Brussels most of his life and spent long periods on the coast) moved permanently to the area. The opening rooms cover the early years of tenebrism and Impressionism. A room is dedicated to views in watercolour of St. -Idesbald and its environs. There is a wall of various small drawn studies and sketches, none labelled, a collection of fragments more or less.

A masterpiece from a private collection, In Praise of Melancholy (1948), shows the painter at the height of his powers. This is one of a series of great reclining nudes that are marked by serene grandeur. Delvaux never painted figures larger or with more detail. The drapery is intensely coloured and the contrast crisp. Delvaux is an artist who used the nude but – great or not – he could not be called a great painter of the nude in the way Balthus might be described. Balthus is curious about the body – both its reality and its plastic potential when manipulated – whereas Delvaux wants to capture the essence that attracts him. Delvaux paints nudes but never nudity, figures but never flesh. Delvaux does enough to evoke the presence of a figure without going so far as to become naturalistic, something true for every element depicted. It is very rare for any sexual feeling to makes its presence felt and this only happens in a few drawings, never in the oil paintings.

The more one sees the more one understands that Delvaux was deeply involved with pre-Modern art, more so than any other Surrealist. He used the vocabulary, and to a lesser degree the technique, of Classical art with a Modern syntax. He employed motifs lifted from found sources and collaged them into settings where the motifs never quite settle. The first (and so far only) serious study of Delvaux’s art written in English is David Scott’s Surrealizing the Nude (1992). Scott’s thesis is that the artist set out to “problematise” academic Classicism. This confuses means for motive. Delvaux did not intend to agitate; in order to achieve the pictorial effects he wanted he had to distort norms of academic practice and naturalism. Although incongruities and irregularities are woven into the fabric of the pictures they are not the subject. Indeed, although these unorthodox combinations are not elided they are not expected to be noticed other than subliminally.

The more one sees the more one understands that Delvaux was deeply involved with pre-Modern art, more so than any other Surrealist. He used the vocabulary, and to a lesser degree the technique, of Classical art with a Modern syntax. He employed motifs lifted from found sources and collaged them into settings where the motifs never quite settle. The first (and so far only) serious study of Delvaux’s art written in English is David Scott’s Surrealizing the Nude (1992). Scott’s thesis is that the artist set out to “problematise” academic Classicism. This confuses means for motive. Delvaux did not intend to agitate; in order to achieve the pictorial effects he wanted he had to distort norms of academic practice and naturalism. Although incongruities and irregularities are woven into the fabric of the pictures they are not the subject. Indeed, although these unorthodox combinations are not elided they are not expected to be noticed other than subliminally.

In 1941 Delvaux revived a conceit from ten years earlier and had skeletons acting as protagonists, inhabiting real domestic interiors – something his female nudes never do. He also tackled episodes of the Passion with skeletons: The Crucifixion, Deposition, Entombment and Lamentation (though notably not the redeeming, mystical parts: the Resurrection and Ascension). These are very peculiar works – intense, bleak, detached yet not ironic and not notably pious – which paraphrase Netherlandish altarpieces. By prematurely curtailing the development of a scene at this stage – or by stripping flesh from Rogier van der Weyden’s Deposition (c. 1435) – the artist leaves the armature of religious iconography nakedly incomplete, thereby short circuiting viewer-subject empathy.

There are paintings including skeletons and female nudes. Delvaux’s encounter with the Spitzner Museum in 1932, a travelling show which juxtaposed lifelike Venuses in somnolent states with anatomical casts, postmortem photographs and skeletons, made a deep impression and led to immediate attempts to capture that frisson in two unsuccessful paintings.

Perhaps the most psychologically charged painting (and, to my mind, his most remarkable picture) is not here. La Visite (1939), the title of which can be translated as The Visit or more properly as The Visitation, the latter with religious overtones, is in a private collection. In a room a naked (rather than nude) woman holds her breasts as a naked young boy enters. He gazes at her breasts and she gazes at his pre-pubertal genitals. Overhead tiny angels trumpet the occurrence. It bears comparison with Balthus’s Guitar Lesson (1934) as a study of psychic tension and sexual discovery. It must have taken a degree of courage for Delvaux to paint such a picture. It is a tremendous, fraught, haunting image, all the more so for being unforced.

A painting such as Horizons (1962) shows what a playful painter Delvaux could be, beyond being a consummate image maker. It is one of a group of strongly horizontally orientated paintings of railways. Cadmium yellow powerfully illuminates the horizon and only slowly does one notice myriad sources of light: streetlamps, lanterns, house lights, train lights, signals, a paraffin lamp, the moon. Seats from old-fashioned train carriages have been situated in the galleries. (Tellingly most of the few British visitors to Museum Delvaux are train enthusiasts rather than art enthusiasts.)

In a number of lit niches are puppets and model trains that Delvaux made while young, as well as spiral-bound sketchpads in which compositions are roughed out in ballpoint. On large sheets he used the laborious technique of cross-hatching in ink then applying washes of ink or watercolour.

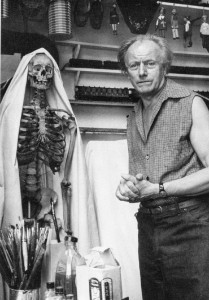

The painter’s eyesight deteriorated badly in his late eighties and eventually was extinguished totally. He painted his last oil in 1986 but continued making drawings until 1989, aged 92. Some of the framing of works on paper is unsympathetic and the lighting would benefit from an upgrade. Although the paintings suffer a little visually from a lack of natural light, the windowless isolation proves immersive. These aspects do not seriously detract from the charm of the museum. The great range and depth of the collection is remarkable. There are genuine masterpieces from all periods in spacious galleries with plenty of supporting material including models, source books, painting paraphernalia and personal documents. There is a recreation of Delvaux’s studio as it was at Avenue des Campanules, Boitsfort, Brussels.

The painter’s eyesight deteriorated badly in his late eighties and eventually was extinguished totally. He painted his last oil in 1986 but continued making drawings until 1989, aged 92. Some of the framing of works on paper is unsympathetic and the lighting would benefit from an upgrade. Although the paintings suffer a little visually from a lack of natural light, the windowless isolation proves immersive. These aspects do not seriously detract from the charm of the museum. The great range and depth of the collection is remarkable. There are genuine masterpieces from all periods in spacious galleries with plenty of supporting material including models, source books, painting paraphernalia and personal documents. There is a recreation of Delvaux’s studio as it was at Avenue des Campanules, Boitsfort, Brussels.

Various figures marginal to Surrealism (Leonor Fini, Claude Cahun and Hans Bellmer, with Louise Bourgeois reclaimed as a Surrealist) have enjoyed renewed attention of late. Delvaux is no less complex than Fini and Bellmer. Delvaux’s art, rich and sophisticated, can be best appreciated detached from Surrealism. Delvaux’s blend of Classicism, Symbolism and Surrealism will never be as popular as the art of Dalí or as accessible as Magritte’s. It deserves to be taken more seriously than it has been. If we assess the status of artist in relation to his ability to compel and fascinate then Delvaux truly is a great artist.

Museum Paul Delvaux, Avenue Paul Delvaux Laan 42, 8670 St.-Idesbald- Koksijde, Belgium, entrance €8. Check for opening hours. www.delvauxmuseum.com, e-mail: info@delvauxmuseum.com

Alexander Adams is an artist and writer based in Berlin.

The Jackdaw, Mar-Apr 2011

Radical Classicist: Alexander Adams visits the museum dedicated to Surrealist painter Paul Delvaux (1887-1994)

Delvaux: Acropolis, 1966

If you have heard of Belgian painter Paul Delvaux (1897-1994) then it is likely to have been in connection with Surrealism. He gets a couple of illustrations in thematic surveys of Surrealism, rarely more. Unless you locate a specialist publication on the artist, it is hard to get an overview of his development. Delvaux is poorly represented in British public collections.

Born near Liège in 1897, Delvaux initially studied architecture in Brussels, though he abandoned his studies because his grades in mathematics were insufficient, transferring to the painting course. Delvaux’s earliest pieces are landscapes composed with a naturalistic palette, later leavened by Impressionism. As is usual for Belgians of this period, the Impressionism is more a form of vivacious naturalism with vibrant lighting effects and vigorous brushwork rather than sustained application of complimentary colour theory. Throughout the late 1920s he picked up and attempted to blend a welter of (often conflicting) influences: Renoir, Cézanne, Modigliani, Ensor. After 1925 one constant emerges: the human figure, often as a nude, as the principal subject. In the late 1920s Delvaux came into the orbit of Flemish Expressionists (less bold and strident than the Germans, they evolved a dull-hued, restrained style dwelling on figures in domestic settings, clearly displaying an attachment to realism).

Yet even as he was painting the most accomplished works of his career, something was nagging at him. He had seen the art of de Chirico and pondered Wiertz’s La Belle Rosine (see Jackdaw no. 95) and felt there was new territory to be discovered. (In 1922 he painted a view of the entrance to Musée Wiertz.) The example of Magritte proved a decisive spur. By 1935 his figures were becoming more normally proportioned, the palette broader and more conventional and the settings ever more precise and significant. He had arrived at his classic mature style.

What is the typical Delvaux? Although there are distinct phases, we can make some generalisations: the subjects are females, often nude, with dreamlike repose in the surrounding of fantastic architecture, generally a blend of classical, neo-classical and 19th century Belgian. Frequently used settings included train stations, town squares, beaches and temples, often nocturnal and deserted and almost exclusively urban rather than pastoral. The technique is direct, the lighting pellucid, the brushwork unobtrusive.

A typical work is Echo (1943) (currently in a Japanese museum): between ancient buildings at night time a woman walks along a road towards the picture plane; behind her are her echoes – two identical versions of her in the same pose. The ground is arid, indicating we are in Near East or Mediterranean lands. Nothing will ever change, no rain fall, no building deteriorate any further. The world we see is in a state of perfect stasis. Of all paintings (Surrealist or otherwise) these come closest to capturing dreamlike states. There is very little here that is literally impossible – no burning giraffes or floating rocks. The poetry resides in the mood evoked by arranging legible motifs.

Delvaux’s personal collection (as one might have guessed, the largest collection of Delvaux paintings in the world) is housed in a museum in St.-Idesbald, on the coast. To get to Museum Delvaux one takes the tram from Ostend south-west to Koksijde-St.-Idesbald (direction De Panne, zone 7, €2 per journey). During summer the one-hour journey with the dunes on one side and the sea on the other must be picturesque but out of season it is rather bleak. The museum is a low brick building in a residential lane less than ten minutes’ walk from the seafront. It was established in 1982, two years before Delvaux (who lived in Brussels most of his life and spent long periods on the coast) moved permanently to the area. The opening rooms cover the early years of tenebrism and Impressionism. A room is dedicated to views in watercolour of St. -Idesbald and its environs. There is a wall of various small drawn studies and sketches, none labelled, a collection of fragments more or less.

A masterpiece from a private collection, In Praise of Melancholy (1948), shows the painter at the height of his powers. This is one of a series of great reclining nudes that are marked by serene grandeur. Delvaux never painted figures larger or with more detail. The drapery is intensely coloured and the contrast crisp. Delvaux is an artist who used the nude but – great or not – he could not be called a great painter of the nude in the way Balthus might be described. Balthus is curious about the body – both its reality and its plastic potential when manipulated – whereas Delvaux wants to capture the essence that attracts him. Delvaux paints nudes but never nudity, figures but never flesh. Delvaux does enough to evoke the presence of a figure without going so far as to become naturalistic, something true for every element depicted. It is very rare for any sexual feeling to makes its presence felt and this only happens in a few drawings, never in the oil paintings.

In 1941 Delvaux revived a conceit from ten years earlier and had skeletons acting as protagonists, inhabiting real domestic interiors – something his female nudes never do. He also tackled episodes of the Passion with skeletons: The Crucifixion, Deposition, Entombment and Lamentation (though notably not the redeeming, mystical parts: the Resurrection and Ascension). These are very peculiar works – intense, bleak, detached yet not ironic and not notably pious – which paraphrase Netherlandish altarpieces. By prematurely curtailing the development of a scene at this stage – or by stripping flesh from Rogier van der Weyden’s Deposition (c. 1435) – the artist leaves the armature of religious iconography nakedly incomplete, thereby short circuiting viewer-subject empathy.

There are paintings including skeletons and female nudes. Delvaux’s encounter with the Spitzner Museum in 1932, a travelling show which juxtaposed lifelike Venuses in somnolent states with anatomical casts, postmortem photographs and skeletons, made a deep impression and led to immediate attempts to capture that frisson in two unsuccessful paintings.

Perhaps the most psychologically charged painting (and, to my mind, his most remarkable picture) is not here. La Visite (1939), the title of which can be translated as The Visit or more properly as The Visitation, the latter with religious overtones, is in a private collection. In a room a naked (rather than nude) woman holds her breasts as a naked young boy enters. He gazes at her breasts and she gazes at his pre-pubertal genitals. Overhead tiny angels trumpet the occurrence. It bears comparison with Balthus’s Guitar Lesson (1934) as a study of psychic tension and sexual discovery. It must have taken a degree of courage for Delvaux to paint such a picture. It is a tremendous, fraught, haunting image, all the more so for being unforced.

A painting such as Horizons (1962) shows what a playful painter Delvaux could be, beyond being a consummate image maker. It is one of a group of strongly horizontally orientated paintings of railways. Cadmium yellow powerfully illuminates the horizon and only slowly does one notice myriad sources of light: streetlamps, lanterns, house lights, train lights, signals, a paraffin lamp, the moon. Seats from old-fashioned train carriages have been situated in the galleries. (Tellingly most of the few British visitors to Museum Delvaux are train enthusiasts rather than art enthusiasts.)

In a number of lit niches are puppets and model trains that Delvaux made while young, as well as spiral-bound sketchpads in which compositions are roughed out in ballpoint. On large sheets he used the laborious technique of cross-hatching in ink then applying washes of ink or watercolour.

Various figures marginal to Surrealism (Leonor Fini, Claude Cahun and Hans Bellmer, with Louise Bourgeois reclaimed as a Surrealist) have enjoyed renewed attention of late. Delvaux is no less complex than Fini and Bellmer. Delvaux’s art, rich and sophisticated, can be best appreciated detached from Surrealism. Delvaux’s blend of Classicism, Symbolism and Surrealism will never be as popular as the art of Dalí or as accessible as Magritte’s. It deserves to be taken more seriously than it has been. If we assess the status of artist in relation to his ability to compel and fascinate then Delvaux truly is a great artist.

Museum Paul Delvaux, Avenue Paul Delvaux Laan 42, 8670 St.-Idesbald- Koksijde, Belgium, entrance €8. Check for opening hours. www.delvauxmuseum.com, e-mail: info@delvauxmuseum.com

Alexander Adams is an artist and writer based in Berlin.

The Jackdaw, Mar-Apr 2011

Share: