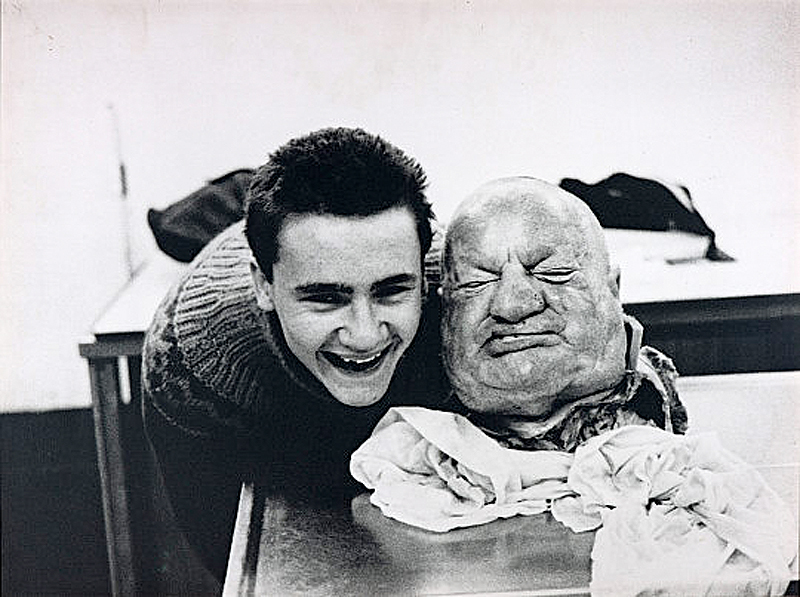

With Dead Head

Glyn Thompson, the pickler’s first teacher, sets the artist’s early record straight…

Hirst scholars will have noted a change in the authorised chronology in the Tate Modern Hirst retrospective catalogue to a venerable biographical item, the entry for March 2002 (The Reliance, Leeds). In the corrected Tate chronology the former title, Damien Hirst’s Art Education, now reads as Fountain Footnotes (The Kominski Suite), the result of due diligence carried out by Loren Hansi Momodu. However, neither titles are strictly correct, since that on the invitation to the private view, delivered to the White Cube in Hoxton Square in late February 2002, read Fountain Footnotes (The Kominski Suite) some drawings, from a private collection, from the archaeology of Damien Hirst’s art education. The exhibition entitled ‘Damien Hirst’s Art Education – Reprised’, opening this month, thus consolidates the position of The Reliance in the authorised Hirst chronology.

As a consequence of this more comprehensive due diligence, the reinstatement of Jacob Kramer to Hirst’s chronology allows new light to be cast on a significant moment in his art education hitherto obscured by the mis-identification of his alma mater as ‘Leeds College of Art’. To his credit, Hirst has corrected this mistake – in On The Way to Work (2001) and in the interview with Nicholas Serota in the Tate Retrospective catalogue – but this has had little effect on either authorised and unauthorized biographies. His own website, and that of his dealer/gallery, White Cube, and Debrett’s, have no entry at all for the years 1983/4, which Hirst spent at Jacob Kramer, and wherever one finds his art education discussed, it is at the fictitious ‘Leeds College of Art’ that he is imagined to have studied.

This omission of Jacob Kramer from the record has focussed attention on Hirst’s post-Goldsmith’s years, encouraging the creation myth of Hirst as self-invented, a construction he appears keen to embrace.

A further consequence of the belated re-instatement of Jacob Kramer to the record is the exhumation of a strand of Hirst’s privileged lineage which blazons the achievement of Harry Thubron, who had worked at Leeds School of Art before moving to Goldsmith’s, where Hirst was to encounter his shade. But Hirst has failed to fully acknowledge his earlier exposure – at Jacob Kramer; contradicting his claim that there he learnt his art history from books and magazines, in History of Art lectures delivered by myself, Hirst witnessed rare images of Thubron’s own work, both in and absent from the record, work by his students, and exemplars from the history of art. The breadth and range of thematic and visual references the art history lectures provided offers a rare window onto Hirst’s early art education, and it is fortunate for scholarship that the notes, and slides, for every lecture, remain in my personal archive.

Such lack of historical accuracy may of course be due as much to memory lapse as myth-making; after all, in speaking to Nicholas Serota in 2011, Hirst was casting his mind back almost thirty event-filled years. But in recounting that “I never looked beyond Leeds – it was where I lived. I’d been unemployed for a year or so … I thought I’d go to art school. I did a one-year Foundation course at Leeds…” Hirst misleads since, born in 1965 and enrolling at Kramer at the age of 18, he could not have been unemployed for a year or so before leaving Jacob Kramer in 1984. Perhaps the reprise, in 1991, one year after he began the Natural History series, of the 1981 self-portrait photograph of himself at the Leeds University medical school morgue, entitled With Dead Head, is itself an expression of this sui generis creation myth, since it would seem to have been produced in order to establish a provenance for a subject also seemingly springing fully formed out of nowhere, augmented with Hirst’s citation of the anatomical drawings he produced at the morgue, whose apparent significance surely demanded display at the Tate, or reproduction in the catalogue.

Hirst first addressed in 1990, in public, the subject which subsequently became his motif-à-clef, the topos of Vanitas, the subject addressed by the drawings exhibited at Reliance in 2002.

The third element of his Leeds experience neglected in the record is the core component of the programme he followed at Jacob Kramer, an academic drawing class which all students undertook, under my direction, in the natural history and ethnography sections of the city museum, Hirst’s familiarity with which is confirmed by his description of the very route by which he reached the back-rooms students were privileged to access. The work was required to address not merely aspects of the form and appearance of the objects but also the taxonomic, moral and teleological implications arising from curatorial traditions ideologically circumscribing the display of ‘Nature’, whose epistemological grounding lay in the cabinet of curiosities. This of course imposes an obligation to consider what Hirst is specifically contributing to the subject of Vanitas.

Arising from the above is the question as to what extent the Damien Hirst who attended Jacob Kramer was in possession, albeit only in microcosm, of the aesthetic which was to propel his entire oeuvre, the institutionalized aesthetic of Appropriationism. That the production of the drawings under discussion was institutionalised is not at issue, since all the work submitted for assessment at Jacob Kramer was executed solely as a consequence of the students’ enrolment; only by satisfying the regulations of the institution could their work acquire validation via the imprimatur of the institution – which is why people go to art school. That institutional endorsement is crucial to Hirst’s identity, as his view that “If it’s in the Tate, it must be Art” confirms, is underlined by Ann Gallagher in her introduction to the catalogue; on page 14 she refers to “… Hirst’s early institutional endorsement, his 1991 show at the I.C.A. in London…”

Hirst was introduced to the history of appropriationism as a legitimate strategy in the philosophy and practice of modern art at the very latest at Jacob Kramer, during the history and theory of art lectures delivered, by myself, to all students attending the Foundation course.

Once inscribed within the corpus, in providing a bridge from Hirst’s youthful fascination with the eternal verities to his first mature expressions, the content of the drawings takes on the character of a missing link – as if in attending Jacob Kramer Hirst’s intuitions were for the first time self-consciously critically contextualised by art history and theory. And when so inscribed, the content of the drawings confirms a thematic continuity between Hirst’s deep seated, long-held preoccupations and his mature expressions.

Glyn Thompson

The Jackdaw, Jul-Aug 2012

Damien Hirst’s wonder year

With Dead Head

Glyn Thompson, the pickler’s first teacher, sets the artist’s early record straight…

Hirst scholars will have noted a change in the authorised chronology in the Tate Modern Hirst retrospective catalogue to a venerable biographical item, the entry for March 2002 (The Reliance, Leeds). In the corrected Tate chronology the former title, Damien Hirst’s Art Education, now reads as Fountain Footnotes (The Kominski Suite), the result of due diligence carried out by Loren Hansi Momodu. However, neither titles are strictly correct, since that on the invitation to the private view, delivered to the White Cube in Hoxton Square in late February 2002, read Fountain Footnotes (The Kominski Suite) some drawings, from a private collection, from the archaeology of Damien Hirst’s art education. The exhibition entitled ‘Damien Hirst’s Art Education – Reprised’, opening this month, thus consolidates the position of The Reliance in the authorised Hirst chronology.

As a consequence of this more comprehensive due diligence, the reinstatement of Jacob Kramer to Hirst’s chronology allows new light to be cast on a significant moment in his art education hitherto obscured by the mis-identification of his alma mater as ‘Leeds College of Art’. To his credit, Hirst has corrected this mistake – in On The Way to Work (2001) and in the interview with Nicholas Serota in the Tate Retrospective catalogue – but this has had little effect on either authorised and unauthorized biographies. His own website, and that of his dealer/gallery, White Cube, and Debrett’s, have no entry at all for the years 1983/4, which Hirst spent at Jacob Kramer, and wherever one finds his art education discussed, it is at the fictitious ‘Leeds College of Art’ that he is imagined to have studied.

This omission of Jacob Kramer from the record has focussed attention on Hirst’s post-Goldsmith’s years, encouraging the creation myth of Hirst as self-invented, a construction he appears keen to embrace.

A further consequence of the belated re-instatement of Jacob Kramer to the record is the exhumation of a strand of Hirst’s privileged lineage which blazons the achievement of Harry Thubron, who had worked at Leeds School of Art before moving to Goldsmith’s, where Hirst was to encounter his shade. But Hirst has failed to fully acknowledge his earlier exposure – at Jacob Kramer; contradicting his claim that there he learnt his art history from books and magazines, in History of Art lectures delivered by myself, Hirst witnessed rare images of Thubron’s own work, both in and absent from the record, work by his students, and exemplars from the history of art. The breadth and range of thematic and visual references the art history lectures provided offers a rare window onto Hirst’s early art education, and it is fortunate for scholarship that the notes, and slides, for every lecture, remain in my personal archive.

Such lack of historical accuracy may of course be due as much to memory lapse as myth-making; after all, in speaking to Nicholas Serota in 2011, Hirst was casting his mind back almost thirty event-filled years. But in recounting that “I never looked beyond Leeds – it was where I lived. I’d been unemployed for a year or so … I thought I’d go to art school. I did a one-year Foundation course at Leeds…” Hirst misleads since, born in 1965 and enrolling at Kramer at the age of 18, he could not have been unemployed for a year or so before leaving Jacob Kramer in 1984. Perhaps the reprise, in 1991, one year after he began the Natural History series, of the 1981 self-portrait photograph of himself at the Leeds University medical school morgue, entitled With Dead Head, is itself an expression of this sui generis creation myth, since it would seem to have been produced in order to establish a provenance for a subject also seemingly springing fully formed out of nowhere, augmented with Hirst’s citation of the anatomical drawings he produced at the morgue, whose apparent significance surely demanded display at the Tate, or reproduction in the catalogue.

Hirst first addressed in 1990, in public, the subject which subsequently became his motif-à-clef, the topos of Vanitas, the subject addressed by the drawings exhibited at Reliance in 2002.

The third element of his Leeds experience neglected in the record is the core component of the programme he followed at Jacob Kramer, an academic drawing class which all students undertook, under my direction, in the natural history and ethnography sections of the city museum, Hirst’s familiarity with which is confirmed by his description of the very route by which he reached the back-rooms students were privileged to access. The work was required to address not merely aspects of the form and appearance of the objects but also the taxonomic, moral and teleological implications arising from curatorial traditions ideologically circumscribing the display of ‘Nature’, whose epistemological grounding lay in the cabinet of curiosities. This of course imposes an obligation to consider what Hirst is specifically contributing to the subject of Vanitas.

Arising from the above is the question as to what extent the Damien Hirst who attended Jacob Kramer was in possession, albeit only in microcosm, of the aesthetic which was to propel his entire oeuvre, the institutionalized aesthetic of Appropriationism. That the production of the drawings under discussion was institutionalised is not at issue, since all the work submitted for assessment at Jacob Kramer was executed solely as a consequence of the students’ enrolment; only by satisfying the regulations of the institution could their work acquire validation via the imprimatur of the institution – which is why people go to art school. That institutional endorsement is crucial to Hirst’s identity, as his view that “If it’s in the Tate, it must be Art” confirms, is underlined by Ann Gallagher in her introduction to the catalogue; on page 14 she refers to “… Hirst’s early institutional endorsement, his 1991 show at the I.C.A. in London…”

Hirst was introduced to the history of appropriationism as a legitimate strategy in the philosophy and practice of modern art at the very latest at Jacob Kramer, during the history and theory of art lectures delivered, by myself, to all students attending the Foundation course.

Once inscribed within the corpus, in providing a bridge from Hirst’s youthful fascination with the eternal verities to his first mature expressions, the content of the drawings takes on the character of a missing link – as if in attending Jacob Kramer Hirst’s intuitions were for the first time self-consciously critically contextualised by art history and theory. And when so inscribed, the content of the drawings confirms a thematic continuity between Hirst’s deep seated, long-held preoccupations and his mature expressions.

Glyn Thompson

The Jackdaw, Jul-Aug 2012

Share: