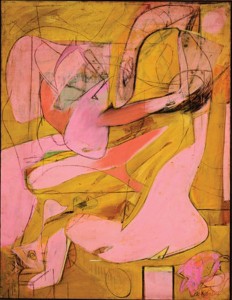

De Kooning: Pink Angels

New York City, home to great collections of art, is never short of key works by important artists to measure against one another. Autumn 2011, three displays have coincided to allow people to compare the skills of a modern master with those of a predecessor who influenced him. Willem de Kooning (1904-1997) revered J.A.D. Ingres (1780-1867) for both his devotion to the human figure and technical skill (in drawing especially). De Kooning vowed he would never paint a tree and his art never strayed too far from the portrait or nude, even at its most abstracted. Likewise, Ingres never manifested much interest in landscape and still-life either. Both painters were noted by peers as being consummate painters of flesh, principally female.

MoMA claim that De Kooning: A Retrospective (until 9 January) is the “first major museum exhibition devoted to the full scope of the career of Willem de Kooning”. As the current survey includes work from 1983-7 not included in a much larger 1983 retrospective shown in Berlin and New York (the current show has 195 works, the earlier one had 280) the press release is technically accurate while being a touch grandiloquent.

Filling the sixth floor of the new MoMA building for the first time, the retrospective provides some surprises and confirms some expectations. (Incidentally, the airy building is both impressive and a sympathetic environment for art.) Firstly, the confirmations: de Kooning could be a great draughtsman. The traditional still-life made at Rotterdam’s Academie is intensely detailed and meticulously observed yet remains vivid and not at all dry. The small pencil drawings in the style of Ingres are effective and memorable. The celebrated paintings of the late 1950s (Door to the River, Suburb in Havana, Gotham News, etc.), which display wide brush marks and acute angles on large canvases, tend towards the dry, vacant and bombastic. The pastels are not successful; their shapes are too diffuse and lack colour intensity.

Secondly, the surprises: de Kooning went through a Matissean phase in the late 1920s following a January 1927 encounter with the French master’s work. The few surviving paintings are highly keyed still-lifes using deep blue and patterning. Another insight is that de Kooning’s early delicacy was not entirely submerged and was occasionally called on later. Clam Diggers (1963) is a creamy, lush oil on card, 51 x 37cms, showing two nude blondes. The colour of the ground forms a sandy surround and oil paint performs as flesh substitute è soft, tactile and alluring. It is a shame de Kooning did not return to this small size and chromatic simplicity more often.

Excavation (1950) drew many viewers, who lost themselves in its swerving, enfolding curves and bejewelled glints among the creamy folds. The interlocking fragments of figures Ingresque and Hellenistic jostle and mesh, animating the picture plane but showing relatively little pictorial depth. It is endlessly seething and – to my eye – is pictorially richer than the women that followed. Five of the great Second Women Series make a memorable sequence at the centre of the display. Woman (1948) is a precursor to the most violently coloured and executed Woman I (1950-2) in MoMA’s collection. The catalogue writers fail to note the influence of Max Beckmann on the stark graphic quality of the orange-segment mouths and eyes during the 1940s. Likewise, the influence of John Marin is overlooked. John Marin was one of the early American Modernists who made semi-Cubist compositions of urban scenes in watercolour and charcoal. He was lionised until he was eclipsed by the Abstract Expressionists and was extremely influential, even representing the USA at the Venice Biennale of 1950 (alongside de Kooning and Pollock). He is now largely neglected and his jauntily angled views of New York with insipid colouring and insistent charcoal delineations are simultaneously crude and tepid. The star form on the top right of Woman (1948) is very characteristic of Marin’s formula of activating dead space around a motif è and an unusually weak device for de Kooning to resort to.

It is hard to know what to make of the bronzes which the artist made during the 1960s and early 1970s. On one level they are three-dimensional translations of his painted and (especially) drawn figures modelled in clay and cast in bronze. They are faithful to their origins but without the ambiguity that is one of the pleasures of the drawings. They are literally “there” the way the drawings – playful and spare – are not and it is the “thereness” that fails to satisfy. They are exactly the sculptures that Francis Bacon imagined making (minus the brushed steel armature and whitewash). The most amusing bronzes are small maquettes, which are barely more than twists of clay. No. 6 (1969) has more than a touch of Rodin’s Iris, Messenger of the Gods (c. 1895). In No. 13 (1969) a rudimentary spread-eagled figure benefits from being set on a found box which acts as an alcove/door, just as the women are depicted in rowing boats in paintings of this period. Again, this echoes Bacon’s practice of juxtaposing loose, organic figures exploiting the plastic potentials of its medium against tightly described geometric surroundings.

The paintings from the 1970s after de Kooning returned from sculpting are the most chromatically dazzling and sumptuous in use of paint in all of his oeuvre. Although a few of the best oils of the period are missing from this selection, the sequence on one wall is a glory. These are what the late 1950s should have been: serpentine trails of ultramarine, black and pink wind around bursts of loosely brushed colour. Have any more purely joyful and playful paintings been made in the late 20th century?

The paintings from 1981–1990 (the “White” or “Ribbon” paintings) are still contested. In these canvases the painter simplified radically, reducing his palette to cadmium red, cadmium yellow and ultramarine, with black being used only for lines and white predominating. The Ribbon paintings are strongly linear, with ribbons of colour gently jinking across the picture surface, sometimes enclosed areas of evenly brushed hues. The Ribbon paintings were made by painting over charcoal tracings (drawn by studio assistants) of old drawings projected onto the primed canvas.

Detractors consider them evidence of waning powers, less tactile and lacking engagement with the characteristics of oil paint. They point to the influence of the assistants in preparing canvases and even selecting the combinations of drawings transferred to the canvas. (Age and alcoholism blunted the artist’s mental capabilities and dementia set in during the 1980s, leading to his family being granted power of attorney over his affairs in 1989.) Curator John Elderfield puts the contrary case for the Ribbon period: that de Kooning made conscious choices and chose to engage with emptiness and serenity and deliberately used the sparseness of drawing to direct his paint handling. He was returning to an approach apparent in earlier phases.

After the slippery delights of the 1970s paintings, these works can’t help but appear thin in every sense. They are less inventive, satisfying and “present”. They lack energy and cannot compel the way even less successful earlier pieces could. However in command of his faculties de Kooning was or was not, the last paintings are less good. Ensor largely lost his inspiration and sense of colour around his 40th year yet painted with clarity and purpose until his late 70s. It is not an issue of competence but of results. Just because, assessed on the ample evidence of this retrospective, de Kooning was a masterful painter does not mean all his paintings are at the highest level.

One artist with ferocious consistency and constancy is Ingres. The group of drawn portraits taken from the Morgan Library’s collection on show at the library’s elegant and humanly scaled galleries demonstrate Ingres to be a consummate professional who never sacrificed psychological insight to the expectations of patrons.

Ingres: Guillon-Lethiere

Ingres was a master technician and portraits of Mlle Joséphine NicaiseLacroix (1813) and M. Guillaume Guillon-Lethière (1815), show his flexibility. The first is largely diagonally hatched on the face while the latter has a mixture of straight hatching and rounded hatching at the brow radiating from the sitter’s left eye. This curving hatching was a common device used by engravers of portrait frontispieces in books of the period. Ingres’s human warmth shines through in his portrait of his wife, where he places himself as an attendant, devotedly marginalised.

The stand-out item, Odalisque and Slave (1839), is a drawing and wash, with touches of brown to soften the grey that might otherwise have been steely. It is in effect a grisaille painting partially achieved through drawing. The female anatomy is subtly altered to suit the picture’s clarity and harmonious rhythm, something Matisse, Picasso and de Kooning would continue to practice. The small strokes and grain of the paper give the picture a powdery presence.

In parallel, the Morgan Library is also hosting a display of early 19th century French drawings borrowed from the Louvre. The Louvre has generously loaned some of the best drawings of the period: Géricault’s Leda and the Swan (1816-7), emphasises the struggle before consummation in dramatic brown wash and white gouache; Francois-Marius Granet’s moody and stygian ink wash View of Rome (c. 1803-12); Ingres’s assured pencil SelfPortrait (1835). There are some bold ink drawings by Delacroix. In a sketch for The Death of Sardanapalus, Delacroix dashes off a patchwork of fabric for the garments of the dying (or supplicating) concubine in a riot of invented pattern. It is done with such carefree energy it reminds one of Picasso at his most daring. This and the other loose pen sketches captivated Delacroix’s Romantic peers and for many now these pieces will hold more appeal than his oils, a number of which have altered as fugitive pigments have discoloured. Delacroix’s tenuous understanding of anatomy is least distracting in the sketches.

Best known for his proficiently sentimental Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1834) in the National Gallery, Paul Delaroche is represented by a marvellously delicate portrait of Antoine Alphonse Montfort (undated) in multiple drawing media. The finely graduated face gazes out sculpturally precise, a single touch of white gouache on his ring gleams in a startlingly present manner. If Delaroche made more portrait drawings of this quality then they deserve to be better known.

There are two pieces which have special emotional power. The first is a portrait by Pierre-Paul Prud’hon of his lover Constance Mayer, a black-and-white chalk drawing on tinted paper (c. 1804). The depiction is lifelike and lively, made with affection and attention. Mayer (a fellow artist) is attired casually. She turns to look past the viewer, head tilted, smiling. When, in 1821, Prud’hon and Mayer’s relationship reached an impasse, the latter committed suicide. Stricken, Prud’hon gave away the drawing, unable to bear the likeness, and died in 1823.

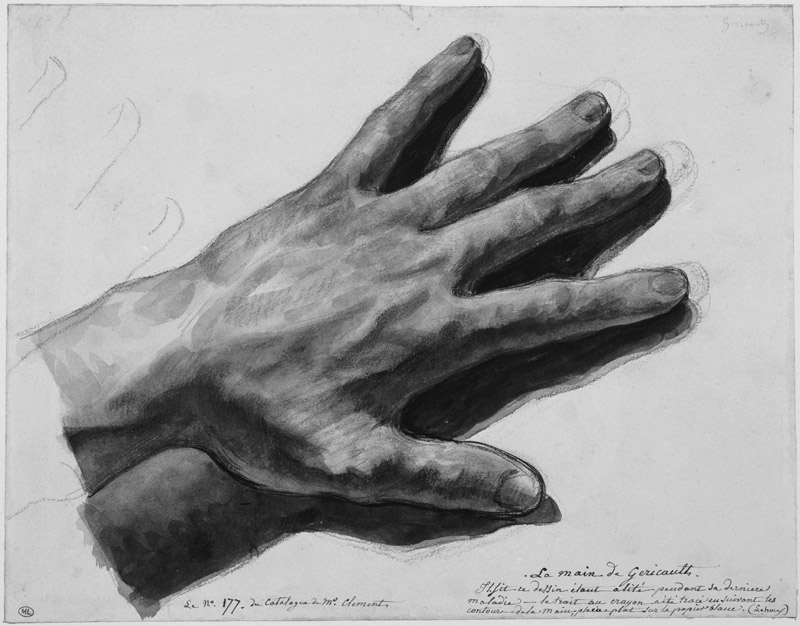

Another masterpiece is Géricault’s watercolour of his left hand (1823/4). Ravaged by cancer and a series of riding accidents, the painter was bedridden at the time and was only weeks from death. His world had contracted to his own body. As he lamented to acolytes all the masterpieces he had planned but never followed through (Géricault was an inveterate perfectionist who only completed one complex composition in oils, The Raft of the Medusa), the artist articulated his frailty and mortality in a slender hand. It thrums with life in the rough red-chalk hatching and loose blue washes even as the man himself was rushing towards oblivion and dissolution.

Another masterpiece is Géricault’s watercolour of his left hand (1823/4). Ravaged by cancer and a series of riding accidents, the painter was bedridden at the time and was only weeks from death. His world had contracted to his own body. As he lamented to acolytes all the masterpieces he had planned but never followed through (Géricault was an inveterate perfectionist who only completed one complex composition in oils, The Raft of the Medusa), the artist articulated his frailty and mortality in a slender hand. It thrums with life in the rough red-chalk hatching and loose blue washes even as the man himself was rushing towards oblivion and dissolution.

De Kooning: A Retrospective, was at MoMA, until January 9th 2012; David, Delacroix, and Revolutionary France: Drawings from the Louvre, was at Morgan Library, until December 31st 2011; Ingres was at the Morgan, Morgan Library, until November 27th 2011.

The Jackdaw Nov-Dec 2011

Lost in New York: painter and critic Alexander Adams discovers an unlikely empathy between Ingres and de Kooning

De Kooning: Pink Angels

New York City, home to great collections of art, is never short of key works by important artists to measure against one another. Autumn 2011, three displays have coincided to allow people to compare the skills of a modern master with those of a predecessor who influenced him. Willem de Kooning (1904-1997) revered J.A.D. Ingres (1780-1867) for both his devotion to the human figure and technical skill (in drawing especially). De Kooning vowed he would never paint a tree and his art never strayed too far from the portrait or nude, even at its most abstracted. Likewise, Ingres never manifested much interest in landscape and still-life either. Both painters were noted by peers as being consummate painters of flesh, principally female.

MoMA claim that De Kooning: A Retrospective (until 9 January) is the “first major museum exhibition devoted to the full scope of the career of Willem de Kooning”. As the current survey includes work from 1983-7 not included in a much larger 1983 retrospective shown in Berlin and New York (the current show has 195 works, the earlier one had 280) the press release is technically accurate while being a touch grandiloquent.

Filling the sixth floor of the new MoMA building for the first time, the retrospective provides some surprises and confirms some expectations. (Incidentally, the airy building is both impressive and a sympathetic environment for art.) Firstly, the confirmations: de Kooning could be a great draughtsman. The traditional still-life made at Rotterdam’s Academie is intensely detailed and meticulously observed yet remains vivid and not at all dry. The small pencil drawings in the style of Ingres are effective and memorable. The celebrated paintings of the late 1950s (Door to the River, Suburb in Havana, Gotham News, etc.), which display wide brush marks and acute angles on large canvases, tend towards the dry, vacant and bombastic. The pastels are not successful; their shapes are too diffuse and lack colour intensity.

Secondly, the surprises: de Kooning went through a Matissean phase in the late 1920s following a January 1927 encounter with the French master’s work. The few surviving paintings are highly keyed still-lifes using deep blue and patterning. Another insight is that de Kooning’s early delicacy was not entirely submerged and was occasionally called on later. Clam Diggers (1963) is a creamy, lush oil on card, 51 x 37cms, showing two nude blondes. The colour of the ground forms a sandy surround and oil paint performs as flesh substitute è soft, tactile and alluring. It is a shame de Kooning did not return to this small size and chromatic simplicity more often.

Excavation (1950) drew many viewers, who lost themselves in its swerving, enfolding curves and bejewelled glints among the creamy folds. The interlocking fragments of figures Ingresque and Hellenistic jostle and mesh, animating the picture plane but showing relatively little pictorial depth. It is endlessly seething and – to my eye – is pictorially richer than the women that followed. Five of the great Second Women Series make a memorable sequence at the centre of the display. Woman (1948) is a precursor to the most violently coloured and executed Woman I (1950-2) in MoMA’s collection. The catalogue writers fail to note the influence of Max Beckmann on the stark graphic quality of the orange-segment mouths and eyes during the 1940s. Likewise, the influence of John Marin is overlooked. John Marin was one of the early American Modernists who made semi-Cubist compositions of urban scenes in watercolour and charcoal. He was lionised until he was eclipsed by the Abstract Expressionists and was extremely influential, even representing the USA at the Venice Biennale of 1950 (alongside de Kooning and Pollock). He is now largely neglected and his jauntily angled views of New York with insipid colouring and insistent charcoal delineations are simultaneously crude and tepid. The star form on the top right of Woman (1948) is very characteristic of Marin’s formula of activating dead space around a motif è and an unusually weak device for de Kooning to resort to.

It is hard to know what to make of the bronzes which the artist made during the 1960s and early 1970s. On one level they are three-dimensional translations of his painted and (especially) drawn figures modelled in clay and cast in bronze. They are faithful to their origins but without the ambiguity that is one of the pleasures of the drawings. They are literally “there” the way the drawings – playful and spare – are not and it is the “thereness” that fails to satisfy. They are exactly the sculptures that Francis Bacon imagined making (minus the brushed steel armature and whitewash). The most amusing bronzes are small maquettes, which are barely more than twists of clay. No. 6 (1969) has more than a touch of Rodin’s Iris, Messenger of the Gods (c. 1895). In No. 13 (1969) a rudimentary spread-eagled figure benefits from being set on a found box which acts as an alcove/door, just as the women are depicted in rowing boats in paintings of this period. Again, this echoes Bacon’s practice of juxtaposing loose, organic figures exploiting the plastic potentials of its medium against tightly described geometric surroundings.

The paintings from the 1970s after de Kooning returned from sculpting are the most chromatically dazzling and sumptuous in use of paint in all of his oeuvre. Although a few of the best oils of the period are missing from this selection, the sequence on one wall is a glory. These are what the late 1950s should have been: serpentine trails of ultramarine, black and pink wind around bursts of loosely brushed colour. Have any more purely joyful and playful paintings been made in the late 20th century?

The paintings from 1981–1990 (the “White” or “Ribbon” paintings) are still contested. In these canvases the painter simplified radically, reducing his palette to cadmium red, cadmium yellow and ultramarine, with black being used only for lines and white predominating. The Ribbon paintings are strongly linear, with ribbons of colour gently jinking across the picture surface, sometimes enclosed areas of evenly brushed hues. The Ribbon paintings were made by painting over charcoal tracings (drawn by studio assistants) of old drawings projected onto the primed canvas.

Detractors consider them evidence of waning powers, less tactile and lacking engagement with the characteristics of oil paint. They point to the influence of the assistants in preparing canvases and even selecting the combinations of drawings transferred to the canvas. (Age and alcoholism blunted the artist’s mental capabilities and dementia set in during the 1980s, leading to his family being granted power of attorney over his affairs in 1989.) Curator John Elderfield puts the contrary case for the Ribbon period: that de Kooning made conscious choices and chose to engage with emptiness and serenity and deliberately used the sparseness of drawing to direct his paint handling. He was returning to an approach apparent in earlier phases.

After the slippery delights of the 1970s paintings, these works can’t help but appear thin in every sense. They are less inventive, satisfying and “present”. They lack energy and cannot compel the way even less successful earlier pieces could. However in command of his faculties de Kooning was or was not, the last paintings are less good. Ensor largely lost his inspiration and sense of colour around his 40th year yet painted with clarity and purpose until his late 70s. It is not an issue of competence but of results. Just because, assessed on the ample evidence of this retrospective, de Kooning was a masterful painter does not mean all his paintings are at the highest level.

One artist with ferocious consistency and constancy is Ingres. The group of drawn portraits taken from the Morgan Library’s collection on show at the library’s elegant and humanly scaled galleries demonstrate Ingres to be a consummate professional who never sacrificed psychological insight to the expectations of patrons.

Ingres: Guillon-Lethiere

Ingres was a master technician and portraits of Mlle Joséphine NicaiseLacroix (1813) and M. Guillaume Guillon-Lethière (1815), show his flexibility. The first is largely diagonally hatched on the face while the latter has a mixture of straight hatching and rounded hatching at the brow radiating from the sitter’s left eye. This curving hatching was a common device used by engravers of portrait frontispieces in books of the period. Ingres’s human warmth shines through in his portrait of his wife, where he places himself as an attendant, devotedly marginalised.

The stand-out item, Odalisque and Slave (1839), is a drawing and wash, with touches of brown to soften the grey that might otherwise have been steely. It is in effect a grisaille painting partially achieved through drawing. The female anatomy is subtly altered to suit the picture’s clarity and harmonious rhythm, something Matisse, Picasso and de Kooning would continue to practice. The small strokes and grain of the paper give the picture a powdery presence.

In parallel, the Morgan Library is also hosting a display of early 19th century French drawings borrowed from the Louvre. The Louvre has generously loaned some of the best drawings of the period: Géricault’s Leda and the Swan (1816-7), emphasises the struggle before consummation in dramatic brown wash and white gouache; Francois-Marius Granet’s moody and stygian ink wash View of Rome (c. 1803-12); Ingres’s assured pencil SelfPortrait (1835). There are some bold ink drawings by Delacroix. In a sketch for The Death of Sardanapalus, Delacroix dashes off a patchwork of fabric for the garments of the dying (or supplicating) concubine in a riot of invented pattern. It is done with such carefree energy it reminds one of Picasso at his most daring. This and the other loose pen sketches captivated Delacroix’s Romantic peers and for many now these pieces will hold more appeal than his oils, a number of which have altered as fugitive pigments have discoloured. Delacroix’s tenuous understanding of anatomy is least distracting in the sketches.

Best known for his proficiently sentimental Execution of Lady Jane Grey (1834) in the National Gallery, Paul Delaroche is represented by a marvellously delicate portrait of Antoine Alphonse Montfort (undated) in multiple drawing media. The finely graduated face gazes out sculpturally precise, a single touch of white gouache on his ring gleams in a startlingly present manner. If Delaroche made more portrait drawings of this quality then they deserve to be better known.

There are two pieces which have special emotional power. The first is a portrait by Pierre-Paul Prud’hon of his lover Constance Mayer, a black-and-white chalk drawing on tinted paper (c. 1804). The depiction is lifelike and lively, made with affection and attention. Mayer (a fellow artist) is attired casually. She turns to look past the viewer, head tilted, smiling. When, in 1821, Prud’hon and Mayer’s relationship reached an impasse, the latter committed suicide. Stricken, Prud’hon gave away the drawing, unable to bear the likeness, and died in 1823.

De Kooning: A Retrospective, was at MoMA, until January 9th 2012; David, Delacroix, and Revolutionary France: Drawings from the Louvre, was at Morgan Library, until December 31st 2011; Ingres was at the Morgan, Morgan Library, until November 27th 2011.

The Jackdaw Nov-Dec 2011

Share: