Explanations to date concerning this marvellous figure are inadequate.

Explanations to date concerning this marvellous figure are inadequate.

What precisely is it? Where did it come from? And what date is it?

The Motya Charioteer stood for six weeks until the middle of September in the large gallery housing the Parthenon pediments and frieze in the British Museum. It was worth making a special effort to see it more than once as it is among few great works – it is reproduced as standard in most of the better literature of classicism – of ancient art to visit London in recent times. Certainly nothing else in the Cultural Olympiad – so lavishly praised by those who organised it and their dutiful footsoldiers – could touch it for sculptural virtuosity and immediate aesthetic impact. The time required to take in this figure properly far exceeded the twenty minutes needed to dawdle through Damien Hirst’s retrospective at Tate Modern – that institution’s imaginative and unexpected contribution to the art events stapled to the Olympics’ coattails. Additionally the Motya Charioteer was given free of charge.

This was no off-the-shelf piece like so many antique sculptures in so many museums. On the contrary, it looked to be the work of an important artist, whose name we ought to know, and even may know, but which we will never now discover. The material is pale yellow limestone whose origin is described vaguely as “Greek or Turkish” – modern analysis can surely be more specific than this.

It was unearthed in 1979 on the tiny island of Motya off the western coast of Sicily close to Marsala where it is housed in a regional museum from which it is rarely loaned. Universally praised for its beauty, not least in British newspapers when it first went on show at the Museum, it is already considered a key piece in classical sculpture. It was, curiously, found among mainly architectural rubble. Motya was a longstanding Phoenician city fortress until it was conquered following a destructive siege by a native Sicilian in 397 BC. It was later taken over by the Carthaginians until in 241 BC it was subsumed into an expanding Roman republic. The debris in which the sculpture was found is said to have been piled up to protect a sanctuary area of the Phoenician city during the siege of 397 BC. Quite why a sculpture of such obvious refinement should have been condemned to a spoil heap is unknown.

Sicily, the larger part of which was a Greek colony, was an area renowned in the ancient world for its successful charioteers and for its horse breeding. It has been speculated that this piece was commissioned by a victorious charioteer in the Greek part of Sicily to celebrate an important triumph in the hippodrome. At some point it was looted by the Phoenicians and taken to Motya where its qualities were not apparently appreciated. If you are a scholar desperately in search of an explanation this seems as fanciful a story as any other wild speculation. (With the scholarship of ancient sculpture it only takes a couple of recountings before a speculation becomes accepted fact.)

Dated circa 460 BC by the British Museum, this makes the Motya Charioteer around a generation earlier than the Parthenon marbles. In textbook terms, the piece is described as Transitional; that is, it bridges the missing link, as it were, between Archaic and so-called Severe sculpture (the kouroi centuries) and the more realistic classical ideal characteristic of the best of the Periclean Acropolis. Another of the ‘missing links’ of the same period, the Kritos Boy, found on the Acropolis, only bears a resemblance to the charioteer in the head.

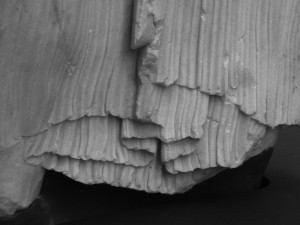

The carving quality of this figure is breathtaking; an otherwise naked body is seen through a light, diaphanous, skin-hugging robe of a crinkle-cut material similar to cheese cloth. In style the piece is a fascinating enigma. Stylised facial features are indicative of an early-to-mid 5th century BC date. The rest of the figure, however, is less hieratic, more realistic, more human, indeed more suggestive of a carving style and understanding of anatomy seen in some of the figures of the Parthenon pediment itself – it anticipates the so-called ‘wet look’ prevalent in carving in the half century following completion of the Parthenon sculptures. One is forced to state that were this charioteer headless, experts would surely have to date him fifty years after the current speculation. There is nothing in Greek sculpture of 460BC which resembles even a little in style the body of the Motya Charioteer from the head down. It could not by itself be called ‘Transitional’, or any other name implying fence-sitting. In terms of its style, wherever it was the body of the charioteer was heading, it had already arrived there.

Being so particular even personal in its details, it is difficult to imagine this figure not having been carved from life, or at least done by reference to drawings. Detailed observations of anatomy are acute and subtle in a figure superlatively athletic. He is built more like a pentathlete than a chariot racer. The only modern equivalent of this chap’s superb physique, especially the buttocks, are those on the most muscular ballet dancers. This fellow has the bodily tone expected of a jumper or a thrower, or at least of a discipline requiring exceptional stamina and strength. Those whose specialism is controlling horses at speed, jockeys, carriage drivers, trotters etc., are not known for their highly developed musculature or domineering size; lightness and agility are more favoured for these pastimes which require deft control and empathy before brute force.

The figure was dug up in 1979 on the tiny island of Motya off the west coast of Sicily, where the sculpture is housed in a regional museum. He is said to represent a charioteer because his long garment – in being long – seems akin to those worn by charioteers in vase decoration and incised on gems. Another charioteer, albeit in bronze, in the Delphi Archaeological Museum, discovered at Delphi in 1879, wears a long dress harnessed at the chest. If you squint at this figure through half-closed eyes from a distance of half a mile you might conclude that the figures are similar, if only in the number of arms and legs. There are, however, significant differences of emphasis between these two works. One is holding reins, and is therefore clearly in position on a chariot. The Motya figure is more informal. Avoiding the flat-footed frontality of earlier wooden poses, the sculptor places the figure’s weight on one leg while gently twisting the torso – the convincing expression of this inflection is best seen from behind. The restrictive fastening for his long robe, which is itself impossibly twisted at the back, is decorative, the metal clasp missing. He was also originally wearing elaborate headgear, probably of copper or silver. Such impedimentary accoutrements would surely not have been worn during the race. Further supporting the informal attitude of this figure, he is attired then not as a recently victorious athlete but for subsequent presentation to the crowd. One hand is louchely resting on his hip. The other arm, amputated near the shoulder, is raised in some sort of acknowledgement or greeting, or even blandishment. It has been proposed that he is attaching his victor’s laurel wreath. This is improbable, the arm being in the wrong place for that action – it is not even close to the angle needed; that is, if other wreath-fingerers in an adjacent BM gallery are indicative of the pose required. Is it likely that he has one hand on his hip and the other fiddling with his laurel. This sort of cartoon campness might have been convincing in Up Pompeii but surely not for the depiction of a great champion. If this fellow is a charioteer, he is being observed at the post-race press conference having slipped into something a little more comfortable.

As close examination reveals he put on his garb like a dressing gown, one side drawn over the other and fastened tightly at the top; in contrast the Delphi charioteer – dated by inscription to 479 BC, and therefore roughly contemporaneous with our more effete fellow – pulled his kit over his head. Though the rear view of the Motya figure suggests that the pose is stretching the drainpipe of fabric taut, the front is decoratively bunched implying a freedom of movement in the fabric at variance with the tension behind. The could be sculptor’s licence, a decorative flourish. Whatever it is doing, it is certainly an inconsistency, and he could not have tolerated such copious billowing cloth while jiggling on the narrow platform of a chariot for fear of dangerously ensnaring himself in the folds. Whether he is a charioteer or not, this is the most impractical gear for the dangerous job of driving at breakneck speed a chariot drawn by four horses.

Please correspond your thoughts on this figure to

David Lee

The Jackdaw September 2012