Fritz Balthaus: Pure Moore

The traditionalist lament for loss of skill is a distraction. The modernists were right about that: skill on its own is not enough. The first step on the road to recovery is to reinstate the visual as the sole and proper domain of art. Once it is generally agreed that art’s impact is essentially visual, the skills to make it so will resurface.

It’s a paradox that we keep visual art in museums, when it’s the only branch of art for which there is no muse. Of the nine Greek muses, there was one for history – Clio – and one for astronomy – Urania – neither of which disciplines we now regard as arts. There was one for tragedy – Melpomene – and one for comedy – Thalia; one for music, naturally – Euterpe – and one for dance – Terpsichore. And there were no fewer than three for verse of different kinds: Polyhymnia for sacred, Erato for love and Calliope for epic poetry. But there were no muses for what we now refer to as the fine arts.

It’s hard to explain why not, unless it has something to do with their parentage. The muses were the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne, memory, and memory was a basic requirement for the practice and perpetuation of the literary, theatrical and musical arts (plus history and astronomy) in the days before pen and paper, let alone computers. Nowadays only actors and dancers need rely on their memories, although they too have written texts and notes when learning their parts. But artists rely on a different sort of memory, a memory of the how rather than the what. For the Greeks, this was another distinguishing factor. The muses’ arts were learned via the ears rather than the eyes, with the exception of dance – and that went with music.

Today we have different denominations and hierarchies. Astronomy and history are out; visual art is in, right up near the top of the table. So preeminent, in fact, has it become that it no longer needs a separate trade description and is classified simply as ‘art’ – except for the purposes of funding, when it is referred to as ‘visual art’. But the strange thing is, the more funding art absorbs the less visual it progressively becomes. Like a disease mimicking the behaviour of other cells, it increases its share of public funding by trespassing on the domains of other arts. How much of the art on show at Manchester International Festival was strictly ‘visual’? From the reviews I read of the exhibition 11 Rooms at Manchester Art Gallery, none. One room contained a live manga avatar, a second a naked woman with a hand-mirror, a third a war veteran standing in a corner, a fourth a man in bed. “In white room after white room you plunge in, 11 times, not knowing what you’ll find there,” wrote Adrian Searle in The Guardian. “More real presences, performances and theatre.” His review, headed ‘Room with No View’, was conspicuous for its avoidance of value judgements. His concluding observation, a propos Robert Wilson’s restaging of Marina Abramovic’s performances, was: “The images keep coming back.” So do traumas and undigested food.

If critics don’t know what category they’re judging in, how can they judge? Contemporary art criticism is based not on visual grounds but on other criteria (which, appropriately, is the name of Damien Hirst’s outlet in New Bond Street). Other muses sit on art’s judging panel – chaired by Clio’s kid sister, the muse of art history – and the critical faculty they use is the ear rather than the eye. The arrival of word processors has accelerated the verbalisation of art. Curators wrap exhibitions in webs of words as if ashamed of their visual nakedness, while press offices seem actively determined to put audiences off with assurances that there’ll be nothing to look at. Take last autumn’s Gabriel Orozco show at Tate Modern. The press release told us that he was “a sculptor of global significance”: that he “draws on the histories of western and Latin American practice”; that he has a “fascination with combining the systematic and the organic”; that his work “has been informed by his extensive travels and his relationship to the various places he visits”. But nowhere did it suggest that his art was a visual pleasure which, in the event, it turned out to be.

Non-visual art is by definition visually boring, so a campaign is now afoot to make ‘boring’ interesting. Two years ago Hoxton Square Gallery organised a competition for the title of ‘Most Boring Drawing’, accompanied by ‘Most Boring’ – A Performance. (Performances were sensibly limited to a single entry, or the jury might still be out). But why should non-visual art be boring when, say, non-visual poetry is not? Because it refuses to use the tools it has been given to stimulate the imagination. The connection of the arts with their mother Mnemosyne is umbilical; it goes a lot deeper than learning by rote. Art works on its audience by triggering memory. An education project at MoMA New York has discovered that, in front of paintings, previously vegetative Alzheimer’s patients are spurred to excited recollection. This could explain why ‘iconic’ art is at such a premium, because it occupies a place in our collective memory. Conceptual art, of course, can trigger memory too – we see with our brains – but the memory has to be of something outside itself to elicit a response. It can’t be a memory of another piece of art: ‘exploring issues of representation’ just doesn’t do it. Besides, without a nudge from Ma Mnemosyne artists would have no impetus (other than money) to make work.

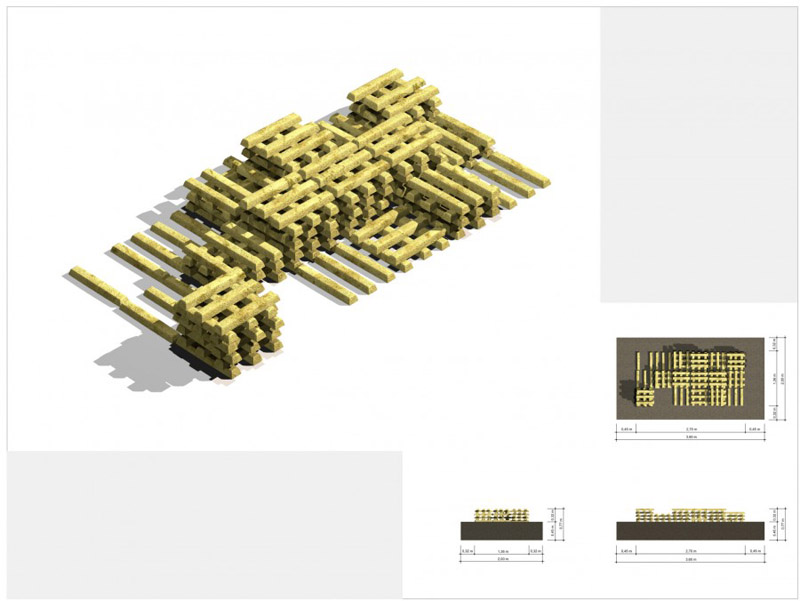

The process of paring away visual association can only go so far before the stimulus is too weak for memory to pick up. For the past hundred years avant-garde art has been on a forced march of progress, casting off aesthetic baggage as it went. First modernism stripped art down to formal beauty, then post-modernism decided that beauty exceeded the baggage allowance and dumped it, along with skill, by the side of the road, replacing it with found objects picked up en route. Last to go, ironically, was monetary value, now the principal support for the whole flimsy structure. The situation has been succinctly summed up by German artist Fritz Balthaus in his sculpture Pure Moore, a stack of 221 bronze bars representing the 2.1-tonne Reclining Figure stolen for scrap from outside the Henry Moore Foundation in 2005. Appropriately, it is now installed outside the German federal criminal police office in Berlin.

The traditionalist lament for loss of skill is a distraction. The modernists were right about that: skill on its own is not enough. The first step on the road to recovery is to reinstate the visual as the sole and proper domain of art. Once it is generally agreed that art’s impact is essentially visual, the skills to make it so will resurface. The general public has never stopped responding to the visual, hence its perplexity in front of much contemporary art. All that’s needed now is the insistence that, to qualify for funding, visual art has to be overwhelmingly visual – as opposed to just visible – and our problems will vanish. So let’s drop the ‘fine’ and accentuate the ‘visual’. ‘Fine’ is a value judgment that has to be earned; ‘visual’ is a simple and crucial criterion by which to judge whether a piece of art is good or bad. Enforce it, and we may find our misnamed museums restocked with things that are worth looking at.

The Jackdaw Sept-Oct 2011

Non-visual art: Laura Gascoigne argues for a restoration of the visual

Fritz Balthaus: Pure Moore

The traditionalist lament for loss of skill is a distraction. The modernists were right about that: skill on its own is not enough. The first step on the road to recovery is to reinstate the visual as the sole and proper domain of art. Once it is generally agreed that art’s impact is essentially visual, the skills to make it so will resurface.

It’s a paradox that we keep visual art in museums, when it’s the only branch of art for which there is no muse. Of the nine Greek muses, there was one for history – Clio – and one for astronomy – Urania – neither of which disciplines we now regard as arts. There was one for tragedy – Melpomene – and one for comedy – Thalia; one for music, naturally – Euterpe – and one for dance – Terpsichore. And there were no fewer than three for verse of different kinds: Polyhymnia for sacred, Erato for love and Calliope for epic poetry. But there were no muses for what we now refer to as the fine arts.

It’s hard to explain why not, unless it has something to do with their parentage. The muses were the daughters of Zeus and Mnemosyne, memory, and memory was a basic requirement for the practice and perpetuation of the literary, theatrical and musical arts (plus history and astronomy) in the days before pen and paper, let alone computers. Nowadays only actors and dancers need rely on their memories, although they too have written texts and notes when learning their parts. But artists rely on a different sort of memory, a memory of the how rather than the what. For the Greeks, this was another distinguishing factor. The muses’ arts were learned via the ears rather than the eyes, with the exception of dance – and that went with music.

Today we have different denominations and hierarchies. Astronomy and history are out; visual art is in, right up near the top of the table. So preeminent, in fact, has it become that it no longer needs a separate trade description and is classified simply as ‘art’ – except for the purposes of funding, when it is referred to as ‘visual art’. But the strange thing is, the more funding art absorbs the less visual it progressively becomes. Like a disease mimicking the behaviour of other cells, it increases its share of public funding by trespassing on the domains of other arts. How much of the art on show at Manchester International Festival was strictly ‘visual’? From the reviews I read of the exhibition 11 Rooms at Manchester Art Gallery, none. One room contained a live manga avatar, a second a naked woman with a hand-mirror, a third a war veteran standing in a corner, a fourth a man in bed. “In white room after white room you plunge in, 11 times, not knowing what you’ll find there,” wrote Adrian Searle in The Guardian. “More real presences, performances and theatre.” His review, headed ‘Room with No View’, was conspicuous for its avoidance of value judgements. His concluding observation, a propos Robert Wilson’s restaging of Marina Abramovic’s performances, was: “The images keep coming back.” So do traumas and undigested food.

If critics don’t know what category they’re judging in, how can they judge? Contemporary art criticism is based not on visual grounds but on other criteria (which, appropriately, is the name of Damien Hirst’s outlet in New Bond Street). Other muses sit on art’s judging panel – chaired by Clio’s kid sister, the muse of art history – and the critical faculty they use is the ear rather than the eye. The arrival of word processors has accelerated the verbalisation of art. Curators wrap exhibitions in webs of words as if ashamed of their visual nakedness, while press offices seem actively determined to put audiences off with assurances that there’ll be nothing to look at. Take last autumn’s Gabriel Orozco show at Tate Modern. The press release told us that he was “a sculptor of global significance”: that he “draws on the histories of western and Latin American practice”; that he has a “fascination with combining the systematic and the organic”; that his work “has been informed by his extensive travels and his relationship to the various places he visits”. But nowhere did it suggest that his art was a visual pleasure which, in the event, it turned out to be.

Non-visual art is by definition visually boring, so a campaign is now afoot to make ‘boring’ interesting. Two years ago Hoxton Square Gallery organised a competition for the title of ‘Most Boring Drawing’, accompanied by ‘Most Boring’ – A Performance. (Performances were sensibly limited to a single entry, or the jury might still be out). But why should non-visual art be boring when, say, non-visual poetry is not? Because it refuses to use the tools it has been given to stimulate the imagination. The connection of the arts with their mother Mnemosyne is umbilical; it goes a lot deeper than learning by rote. Art works on its audience by triggering memory. An education project at MoMA New York has discovered that, in front of paintings, previously vegetative Alzheimer’s patients are spurred to excited recollection. This could explain why ‘iconic’ art is at such a premium, because it occupies a place in our collective memory. Conceptual art, of course, can trigger memory too – we see with our brains – but the memory has to be of something outside itself to elicit a response. It can’t be a memory of another piece of art: ‘exploring issues of representation’ just doesn’t do it. Besides, without a nudge from Ma Mnemosyne artists would have no impetus (other than money) to make work.

The process of paring away visual association can only go so far before the stimulus is too weak for memory to pick up. For the past hundred years avant-garde art has been on a forced march of progress, casting off aesthetic baggage as it went. First modernism stripped art down to formal beauty, then post-modernism decided that beauty exceeded the baggage allowance and dumped it, along with skill, by the side of the road, replacing it with found objects picked up en route. Last to go, ironically, was monetary value, now the principal support for the whole flimsy structure. The situation has been succinctly summed up by German artist Fritz Balthaus in his sculpture Pure Moore, a stack of 221 bronze bars representing the 2.1-tonne Reclining Figure stolen for scrap from outside the Henry Moore Foundation in 2005. Appropriately, it is now installed outside the German federal criminal police office in Berlin.

The traditionalist lament for loss of skill is a distraction. The modernists were right about that: skill on its own is not enough. The first step on the road to recovery is to reinstate the visual as the sole and proper domain of art. Once it is generally agreed that art’s impact is essentially visual, the skills to make it so will resurface. The general public has never stopped responding to the visual, hence its perplexity in front of much contemporary art. All that’s needed now is the insistence that, to qualify for funding, visual art has to be overwhelmingly visual – as opposed to just visible – and our problems will vanish. So let’s drop the ‘fine’ and accentuate the ‘visual’. ‘Fine’ is a value judgment that has to be earned; ‘visual’ is a simple and crucial criterion by which to judge whether a piece of art is good or bad. Enforce it, and we may find our misnamed museums restocked with things that are worth looking at.

The Jackdaw Sept-Oct 2011

Share: